Case

A 72-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension and social history of tobacco use presented to the ED with chest pain and abdominal pain. His vital signs at presentation were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; blood pressure, 80/40 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/minute; temperature, afebrile. His oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. The patient was alert and oriented; his abdomen was soft with no reproducible tenderness to palpation and without a palpable mass. The remainder of the physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. An electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia with left ventricular hypertrophy, and a chest X-ray was read as no acute process by radiology services. Since the patient’s creatinine level was elevated at 3.5 mg/dL, the use of radiocontrast media relatively contraindicated.

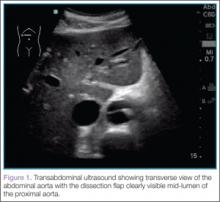

To quickly assess the patient, the treating emergency physician (EP) performed a limited transabdominal ultrasound at the bedside, which revealed an intimal flap in the abdominal aorta in the transverse plane visible at the subcostal margin (Figure 1). The longitudinal view demonstrated the intimal flap clearly, but with no clear point of origin in the abdominal portion of the aorta (Figure 2).

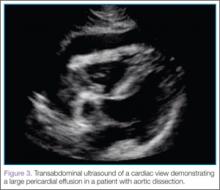

The subcostal cardiac view also revealed the cause for the patient’s hemodynamic instability: a large pericardial effusion with evidence of early acute pericardial tamponade via right atrial collapse (Figure 3).

The patient was taken to the operating room within 20 minutes of arrival to the ED. Expedient diagnosis of both the presence and extent of his aortic dissection and its complications by bedside ultrasound facilitated early and aggressive management of this life-threatening disease process.

Imaging Techniques

Abdominal Aorta

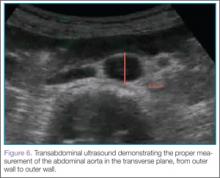

Ultrasound of the abdominal aorta begins with the use of a curvilinear probe, starting in the transverse plane with the probe marker pointing toward the patient’s right side (ie, the 9-o’clock position). The probe should scan the epigastrium, which is located just below the xiphoid process (Figure 4).

For orientation, the clinician should identify the vertebral body, which will appear as a dark and rounded object at the bottom center of the screen with a dark shadow behind it. Both the aorta and inferior vena cava (IVC) will be visualized just superficial to the vertebral body; the aorta typically appears anterior to the vertebral body, with the IVC slightly to the right of it. The amount of pressure applied for visualization of these structures will vary depending on the patient’s body habitus and volume status (Figure 5).

Once orientation is established and there is a clear transverse view of the aorta, calipers are used to measure the diameter of the aorta from superficial to deep, measuring from outer wall to outer wall (Figure 6).

Next, the clinician should scan the probe caudally as he or she follows the aorta down to the level of the bifurcation into the iliac vessels, near the level of the umbilicus (Figure 7).

Then, rotating the probe clockwise 90˚ to place the probe marker in the 12-o’clock position, the abdominal aorta can be measured in the long axis, giving a broad overview of the entire structure (Figure 8).

Identification of an undulating intimal flap is highly specific for the diagnosis of aortic dissection.

Thoracic Aorta

After imaging of the abdominal aorta is complete, a phased array probe is used to scan the thoracic aorta, beginning with a subxiphoid view of the heart. The probe should be placed in the transverse plane, just inferior to the xiphoid process and with the probe marker aimed toward the patient’s right side (ie, the 9-o’clock position). Next, the probe is angled cephalad and slightly toward the patient’s left shoulder, nearly laying it flat on the abdomen, using the liver as the acoustic window. As with abdominal ultrasound, depending on the patient’s body habitus and anatomy, the depth may need to be adjusted for optimal view. This is one of the best views when evaluating for pericardial effusion, which will appear as a dark or anechoic stripe surrounding the heart (Figure 3).

After this view is complete, the clinician should proceed to scan the parasternal long axis view to evaluate the aortic outflow track and descending aorta. The cardiac probe should be placed in the left third or fourth intercostal space with the probe marker angled toward the patient’s right shoulder (ie, the 10- to 11-o’clock position). Proceeding from superficial to deep on the screen, the right ventricle, left ventricle and aortic outflow tract, left atrium, and then the descending aorta (Figure 9) will be visualized.

The two main areas to assess closely are the aortic outflow tract and the descending aorta. While looking at the aortic outflow tract, evidence of aortic regurgitation or a linear echodensity within the aortic root may be seen, suggestive of the intimal flap occurring in aortic dissection. Focusing on the descending aorta, the clinician should again look for a linear echodensity across the aorta, which represents the intimal flap (red highlighted area, Figure 9).