Case

A 2-year-old girl was carried into the ED after falling off her bed earlier in the evening. The parents did not see the child fall, but heard her crying in her room. On physical examination, the patient was in a lot of pain, would not move her left arm, and had a left elbow effusion. The radial pulse was strong, and she was able to move all of her fingers but would not move her elbow. A lateral X-ray taken of the left elbow is shown below (Figure 1).

Supracondylar Fractures

Supracondylar fractures are the most common pediatric elbow injury and disposition can range from outpatient follow-up to urgent surgical intervention. The average age of presentation is between 3 to 10 years, and the injury typically results from a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with hyperextension of the elbow. Supracondylar fractures may also occur after a direct blow to the elbow or hyperflexion.1

The supracondylar area in children, the distal portion of the humerus, is thin and weak. The force transmitted to this region by a direct blow or FOOSH injury can fracture the humerus. The brachial artery runs along the anterior humerus and can easily sustain injury. Median, ulnar, or radial nerve injuries are also common and can result in permanent disability.2 Immediate neurovascular examination is mandatory, and diminished or absent pulses, poor perfusion, and pallor are signs of ischemia. Examination should include assessment of the radial pulse and the sensory and motor function of the median, radial, and ulnar nerves. To test the median nerve (via the anterior interosseous branch), ask the patient make an “OK” sign with his or her fingers; to test the radial nerve, instruct the child to make a “thumb’s up” sign; and to test the ulnar nerve, have the child hold his or her fingers spread-out against resistance. In addition, sensation of the palmer and dorsal surfaces and in between the fingers should be confirmed.

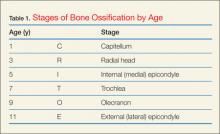

Plain radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP), oblique, and true lateral views, should be obtained. Interpretation of pediatric elbow films can be difficult, and the stages of ossification must be considered. The helpful acronym for remembering the order of bone ossification is CRITOE (capitellum, radial head, internal [medial] epicondyle, trochlea, olecranon, and external [lateral] epicondyle) (Table 1).

If the anterior humeral line—a line drawn through the anterior cortex of the humerus—fails to intersect the capitellum in its middle third, fracture of the distal humerus is present (Figure 2). The radial head should be aligned with the capitellum. Close inspection for a posterior fat pad, or “sail sign” is imperative as it indicates hemorrhage, joint effusion, or occult fracture. The presence of an anterior fat pad can be a normal variant; however, if the pad is wide and creates a “sail sign” then fracture must be assumed.1

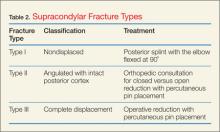

Fracture Types

Pediatric supracondylar fractures are classified into three types (Table 2). Type I fractures may be subtle on X-ray, evident only by a posterior fat pad or only seen on an oblique view. These nondisplaced fractures may be splinted with a long-arm splint. Type II fractures are angulated yet the posterior cortex remains intact. Typically the anterior humeral line is displaced, anteriorly intersecting the anterior third of the capitellum or missing it entirely. These cases require urgent orthopedic consultation for either closed reduction with splinting or open reduction with percutaneous pin placement.Type III supracondylar fractures are completely displaced with a fracture through the anterior and posterior cortex. Since a high-risk of injury to the upper extremity vessels and nerves is associated with these very unstable fractures, routine neurovascular checks (while awaiting operative repair) are required. Supracondylar fractures are often associated with forearm or distal radius fractures; therefore, forearm radiographs should also be obtained.3