Palpitations, the sensory perception of one’s heartbeat, are reported in 16% of primary care patients, from causes that are both cardiac (ie, arrhythmias) and noncardiac.1 Palpitations are usually benign; overall mortality is approximately 1% annually. In fact, a retrospective study found no difference in mortality and morbidity between patients with palpitations and control patients without palpitations.2 However, palpitations can reflect a life-threatening cardiac condition, as we discuss in this article, making careful assessment and targeted, sometimes urgent, intervention important.3

Here, we review the clinical work-up of palpitations, recommended diagnostic testing, and the range of interventions for cardiac arrhythmias—ectopic beats, ventricular tachycardia (VT), and atrial fibrillation (AF).

Cardiac and noncardiac causes of palpitations

In a prospective cohort study of 190 consecutive patients presenting with palpitations, the cause was cardiac in 43%, psychiatric in 31%, and of a miscellaneous nature (including medication, thyrotoxicosis, caffeine, cocaine, anemia, amphetamine, and mastocytosis) in 10%; in 16%, the cause was undetermined.2 In this study, 77% of patients experienced a recurrence of palpitations after their first episode.2

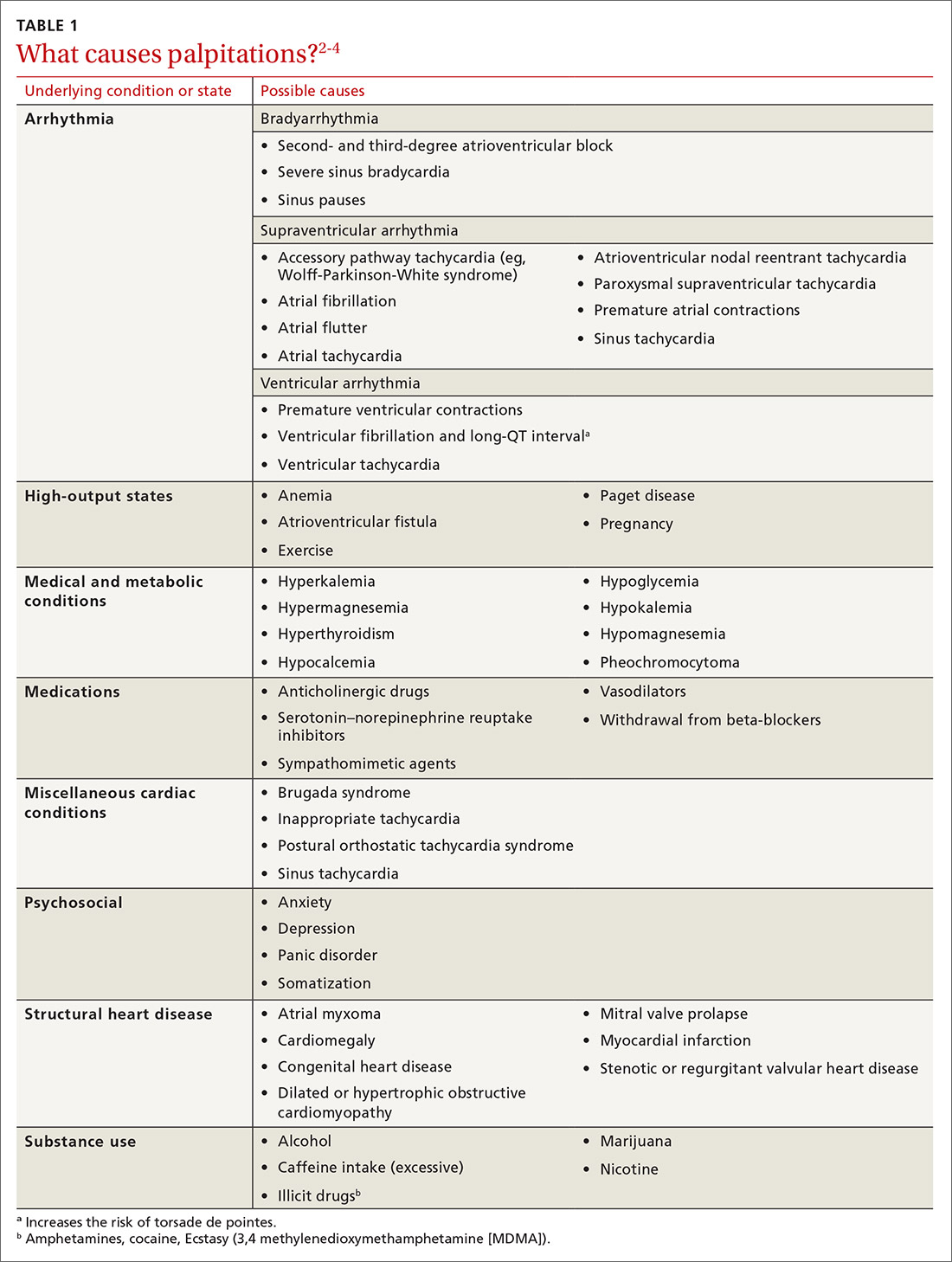

Cardiac arrhythmias, a common cause of palpitations, are differentiated by site of origin—supraventricular and ventricular. Noncardiac causes of palpitations, which we do not discuss here, include metabolic and psychiatric conditions, medications, and substance use. (For a summary of the causes of palpitations, see TABLE 1.2-4)

Common complaint: ectopic beats. Premature atrial contractions (PACs; also known as premature atrial beats, atrial premature complexes, and atrial premature beats) and premature ventricular contractions (PVCs; also known as ventricular premature complexes and ventricular premature beats, and also of a variety of possible causes) result in a feeling of a skipped heartbeat or a flipping sensation in the chest.

The burden of PACs is independently associated with mortality, cardiovascular hospitalization, new-onset AF, and pacemaker implantation. In a multivariate analysis, a PAC burden > 76 beats/d was an independent predictor of mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.2-16); cardiovascular hospitalization (HR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.5); new-onset AF (HR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.4-2.2); and pacemaker implantation (HR = 2.8; 95% CI, 1.9-4.2). Frequent PACs can lead to cardiac remodeling, so more intense follow-up of patients with a high PAC burden might allow for early detection of AF or subclinical cardiac disease.5,6

A burden of PVCs > 24% is associated with an increased risk of PVC-induced cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Polymorphic PVCs are more concerning than monomorphic PVCs because the former suggests the presence of more diffuse, rather than localized, myocardial injury. The presence of frequent (> 1000 beats/d) PVCs warrants evaluation and treatment for underlying structural heart disease and ischemic heart disease. Therapy directed toward underlying heart disease can reduce the frequency of PVCs.7-9

Continue to: The diagnostic work-up