More than HIV, more than malaria.

In terms of preventable deaths, 1.27 million people could have been saved if drug-resistant infections were replaced with infections susceptible to current antibiotics. Furthermore, 4.95 million fewer people would have died if drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infections, researchers estimated.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took some focus off the AMR burden worldwide over the past 2 years, the urgency to address risk to public health did not ebb. In fact, based on the findings, the researchers noted that AMR is now a leading cause of death worldwide.

“If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today,” the researchers noted in the study, published online Jan. 20, 2022, in The Lancet.

“These findings are a warning signal that antibiotic resistance is placing pressure on health care systems and leading to significant health loss,” study author Kevin Ikuta, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We need to continue to adhere to and support infection prevention and control programs, be thoughtful about our antibiotic use, and advocate for increased funding to vaccine discovery and the antibiotic development pipeline,” added Dr. Ikuta, health sciences assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Although many investigators have studied AMR, this study is the largest in scope, covering 204 countries and territories and incorporating data on a comprehensive range of pathogens and pathogen-drug combinations.

Dr. Ikuta, lead author Christopher J.L. Murray, DPhil, and colleagues estimated the global burden of AMR using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019. They specifically looked at rates of death directly attributed to and separately those associated with resistance.

Regional differences

Broken down by 21 regions, Australasia had 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people attributable to AMR, the lowest rate reported. This region also had 28 deaths per 100,000 associated with AMR.

Researchers found the highest rates in western sub-Saharan Africa. Deaths attributable to AMR were 27.3 per 100,000 and associated death rate was 114.8 per 100,000.

Lower- and middle-income regions had the highest AMR death rates, although resistance remains a high-priority issue for high-income countries as well.

“It’s important to take a global perspective on resistant infections because we can learn about regions and countries that are experiencing the greatest burden, information that was previously unknown,” Dr. Ikuta said. “With these estimates policy makers can prioritize regions that are hotspots and would most benefit from additional interventions.”

Furthermore, the study emphasized the global nature of AMR. “We’ve seen over the last 2 years with COVID-19 that this sort of problem doesn’t respect country borders, and high rates of resistance in one location can spread across a region or spread globally pretty quickly,” Dr. Ikuta said.

Leading resistant infections

Lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections together accounted for almost 79% of such deaths linked to AMR.

The six leading pathogens are likely household names among infectious disease specialists. The researchers found Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, each responsible for more than 250,000 AMR-associated deaths.

The study also revealed that resistance to several first-line antibiotic agents often used empirically to treat infections accounted for more than 70% of the AMR-attributable deaths. These included fluoroquinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, cephalosporins, and penicillins.

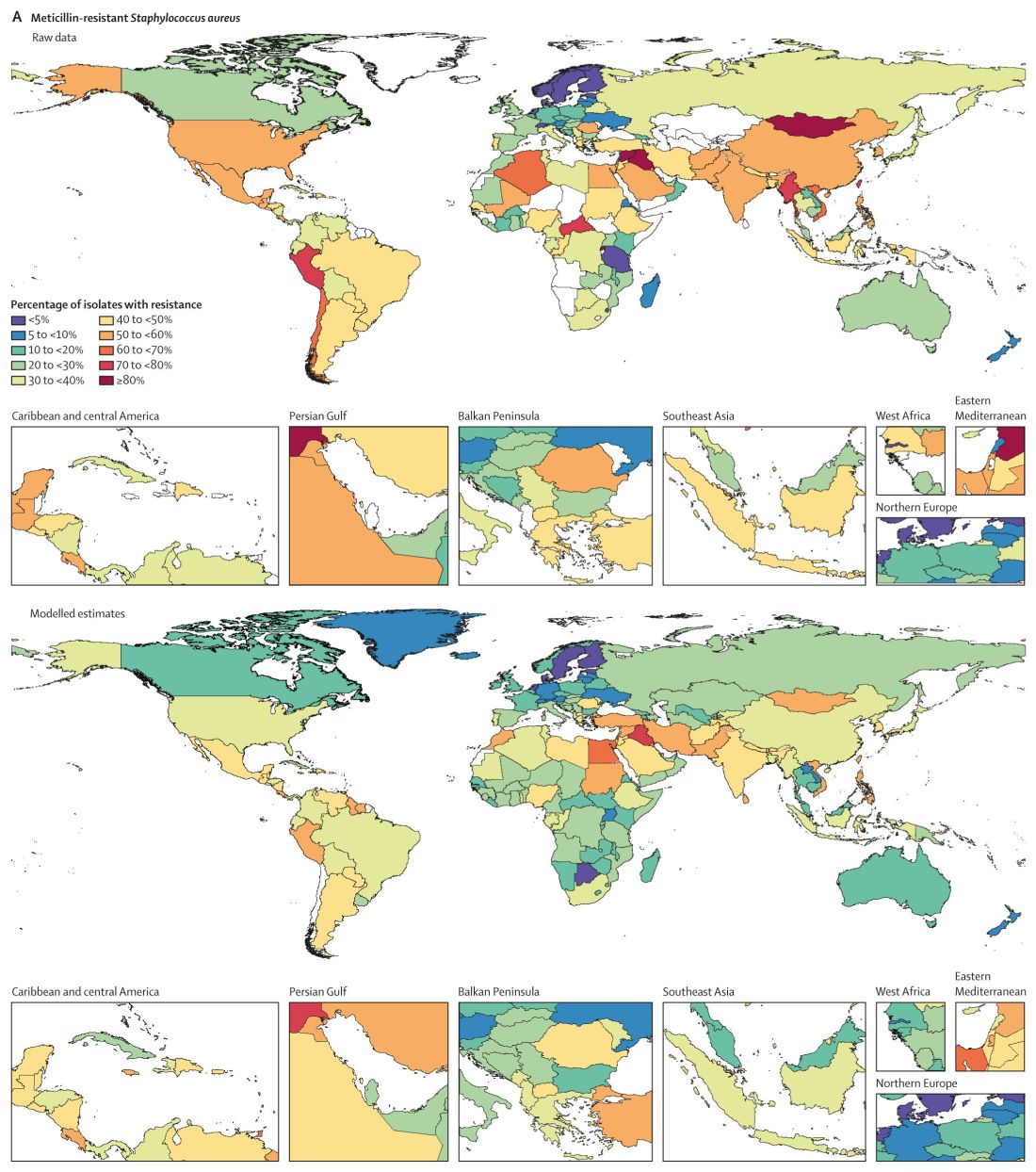

Consistent with previous studies, MRSA stood out as a major cause of mortality. Of 88 different pathogen-drug combinations evaluated, MRSA was responsible for the most mortality: more than 100,000 deaths and 3·5 million disability-adjusted life-years.

The current study findings on MRSA “being a particularly nasty culprit” in AMR infections validates previous work that reported similar results, Vance Fowler, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment on the research. “That is reassuring.”

Potential solutions offered

Dr. Murray and colleagues outlined five strategies to address the challenge of bacterial AMR:

- Infection prevention and control remain paramount in minimizing infections in general and AMR infections in particular.

- More vaccines are needed to reduce the need for antibiotics. “Vaccines are available for only one of the six leading pathogens (S. pneumoniae), although new vaccine programs are underway for S. aureus, E. coli, and others,” the researchers wrote.

- Reduce antibiotic use unrelated to treatment of human disease.

- Avoid using antibiotics for viral infections and other unnecessary indications.

- Invest in new antibiotic development and ensure access to second-line agents in areas without widespread access.

“Identifying strategies that can work to reduce the burden of bacterial AMR – either across a wide range of settings or those that are specifically tailored to the resources available and leading pathogen-drug combinations in a particular setting – is an urgent priority,” the researchers noted.

Admirable AMR research

The results of the study are “startling, but not surprising,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The authors did a “nice job” of addressing both deaths attributable and associated with AMR, Dr. Fowler added. “Those two categories unlock applications, not just in terms of how you interpret it but also what you do about it.”

The deaths attributable to AMR show that there is more work to be done regarding infection control and prevention, Dr. Fowler said, including in areas of the world like lower- and middle-income countries where infection resistance is most pronounced.

The deaths associated with AMR can be more challenging to calculate – people with infections can die for multiple reasons. However, Dr. Fowler applauded the researchers for doing “as good a job as you can” in estimating the extent of associated mortality.

‘The overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance’

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Ramanan Laxminarayan, PhD, MPH, wrote: “As COVID-19 rages on, the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance continues in the shadows. The toll taken by AMR on patients and their families is largely invisible but is reflected in prolonged bacterial infections that extend hospital stays and cause needless deaths.”

Dr. Laxminarayan pointed out an irony with AMR in different regions. Some of the AMR burden in sub-Saharan Africa is “probably due to inadequate access to antibiotics and high infection levels, albeit at low levels of resistance, whereas in south Asia and Latin America, it is because of high resistance even with good access to antibiotics.”

More funding to address AMR is needed, Dr. Laxminarayan noted. “Even the lower end of 911,000 deaths estimated by Murray and colleagues is higher than the number of deaths from HIV, which attracts close to U.S. $50 billion each year. However, global spending on addressing AMR is probably much lower than that.” Dr. Laxminarayan is an economist and epidemiologist affiliated with the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy in Washington, D.C., and the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership in Geneva.

An overlap with COVID-19

The Lancet report is likely “to bring more attention to AMR, especially since so many people have been distracted by COVID, and rightly so,” Dr. Fowler predicted. “The world has had its hands full with COVID.”

The two infections interact in direct ways, Dr. Fowler added. For example, some people hospitalized for COVID-19 for an extended time could develop progressively drug-resistant bacteria – leading to a superinfection.

The overlap could be illustrated by a Venn diagram, he said. A yellow circle could illustrate people with COVID-19 who are asymptomatic or who remain outpatients. Next to that would be a blue circle showing people who develop AMR infections. Where the two circles overlap would be green for those hospitalized who – because of receiving steroids, being on a ventilator, or getting a central line – develop a superinfection.

Official guidance continues

The study comes in the context of recent guidance and federal action on AMR. For example, the Infectious Diseases Society of America released new guidelines for AMR in November 2021 as part of ongoing advice on prevention and treatment of this “ongoing crisis.”

This most recent IDSA guidance addresses three pathogens in particular: AmpC beta-lactamase–producing Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia.

Also in November, the World Health Organization released an updated fact sheet on antimicrobial resistance. The WHO declared AMR one of the world’s top 10 global public health threats. The agency emphasized that misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens. The WHO also pointed out that lack of clean water and sanitation in many areas of the world contribute to spread of microbes, including those resistant to current treatment options.

In September 2021, the Biden administration acknowledged the threat of AMR with allocation of more than $2 billion of the American Rescue Plan money for prevention and treatment of these infections.

Asked if there are any reasons for hope or optimism at this point, Dr. Ikuta said: “Definitely. We know what needs to be done to combat the spread of resistance. COVID-19 has demonstrated the importance of global commitment to infection control measures, such as hand washing and surveillance, and rapid investments in treatments, which can all be applied to antimicrobial resistance.”

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and the U.K. Department of Health and Social Care using U.K. aid funding managed by the Fleming Fund and other organizations provided funding for the study. Dr. Ikuta and Dr. Laxminarayan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fowler reported receiving grants or honoraria, as well as serving as a consultant, for numerous sources. He also reported a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics and serving as chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck).

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.