Paucibacillary tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by few anesthetic hypo- or hyperpigmented lesions and can be accompanied by palpable peripheral nerve enlargements.

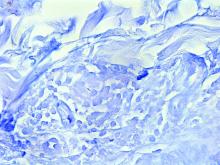

Tuberculoid leprosy presents histologically with epithelioid histiocytes with lymphocytes and Langhans giant cells. Neurotropic granulomas are also characteristic of tuberculoid leprosy. Fite staining allows for the identification of the acid-fast bacilli of M. leprae, which in some cases are quite few in number. The standard mycobacterium stain, Ziehl-Neelsen, is a good option for M. tuberculosis, but because of the relative weak mycolic acid coat of M. leprae, the Fite stain is more appropriate for identifying M. leprae.

Clinically, other than the presence of fewer than five hypoesthetic lesions that are either hypopigmented or erythematous, tuberculoid leprosy often presents with additional peripheral nerve involvement that manifests as numbness and tingling in hands and feet.1 This patient denied any tingling, weakness, or numbness, outside of the anesthetic lesion on his posterior upper arm.

The patient, born in the United States, had a remote history of military travel to Iraq, Kuwait, and the Philippines, but had not traveled internationally within the last 15 years, apart from a cruise to the Bahamas. He denied any known contact with individuals with similar lesions. He denied a history of contact with armadillos, but acknowledged that they are native to where he resides in central Florida, and that he had seen them in his yard.

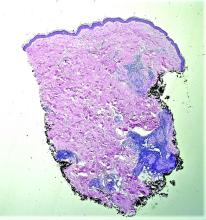

Histopathological examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis with a superficial and deep perivascular, periadnexal, and perineural lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Fite stain revealed rare rod-shaped organisms (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of paucibacillary, tuberculoid leprosy.

The patient’s travel history to highly endemic areas (Middle East), as well as possible environmental contact with armadillos – including contact with soil that the armadillos occupied – could explain plausible modes of transmission. Following consultation with our infectious disease department and the National Hansen’s Disease Program, our patient began a planned course of therapy with 18 months of minocycline, rifampin, and moxifloxacin.

Human-to-human transmission of HD has been well documented; however, zoonotic transmission – specifically via the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) – serves as another suggested means of transmission, especially in the Southeastern United States.2-6 Travel to highly-endemic areas increases the risk of contracting HD, which may take up to 20 years following contact with the bacteria to manifest clinically.

While central Florida was previously thought to be a nonendemic area of disease, the incidence of the disease in this region has increased in recent years.7 Human-to-human transmission, which remains a concern with immigration from highly-endemic regions, occurs via long-term contact with nasal droplets of an infected person.8,9

Many patients in regions with very few cases of leprosy deny travel to other endemic regions and contact with infected people. Thus, zoonotic transmission remains a legitimate concern in the Southeastern United States – accounting, at least in part, for many of the non–human-transmitted cases of leprosy.2,10 We encourage clinicians to maintain a high level of clinical suspicion for leprosy when evaluating patients presenting with hypoesthetic cutaneous lesions and to obtain a travel history and to ask about armadillo exposure.

This case and the photos were submitted by Ms. Smith, from the University of South Florida, Tampa; Dr. Hatch and Dr. Sarriera-Lazaro, from the department of dermatology and cutaneous surgery, University of South Florida; and Dr. Turner and Dr. Beachkofsky, from the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, Tampa. Dr. Bilu Martin edited this case. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Leprosy (Hansen’s Disease), in: “Goldman’s Cecil Medicine,” 24th ed. (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2012: pp. 1950-4.

2. Sharma R et al. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Dec;21(12):2127-34.

3. Lane JE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):714-6.

4. Clark BM et al. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Jun;78(6):962-7.

5. Bruce S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000 Aug;43(2 Pt 1):223-8.

6. Loughry WJ et al. J Wildl Dis. 2009 Jan;45(1):144-52.

7. FDo H. Florida charts: Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy). Health FDo. 2019. https://www.flhealthcharts.gov/ChartsReports/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=NonVitalIndNoGrpCounts.DataViewer&cid=174.

8. Maymone MBC et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):1-14.

9. Scollard DM et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006 Apr;19(2):338-81.

10. Domozych R et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 May 12;2(3):189-92.