VAIL, COLO. – The most recent American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines on management of urinary tract infections do an abrupt about-face by recommending that a voiding cystourethrogram no longer be routinely performed after a first febrile UTI in children aged 2 months to 2 years.

"This is confusing. On a dime, we have changed our recommendations regarding radiographic imaging," noted Dr. John W. Ogle, vice chair and director of pediatrics at Denver Health.

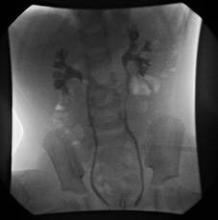

The previous 1999 AAP guidelines on UTIs stated unequivocally that "infants and children 2 months through 2 years of age who have the expected response to antimicrobials should have a sonogram and either voiding cystourethrogram or radionuclide scan at the earliest convenient time" (Pediatrics 1999;10[4 Pt 1]:843-52).

This sharp shift away from this stance in the current guidelines reflects new thinking regarding the pathogenesis of renal scarring, Dr. Ogle said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"The assumption that has been made in the past is that UTI in the presence of reflux is the primary thing that leads to renal scarring. That’s not so clear anymore. Some of what we call scarring may be congenital cortical defects in the kidney that we discover because we’ve studied the child. There are good studies demonstrating that you can have scarring from pyelonephritis with complete absence of reflux," said Dr. Ogle, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The operative hypothesis up until the current guidelines were released in 2011 (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610) was that identifying reflux via a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) allowed physicians to intervene surgically or with prophylactic antimicrobials to prevent further reflux nephropathy with further scarring.

"The evidence seems to be quite clear now that the interventions don’t change those important outcomes of renal scarring. So why look for the reflux? Why do the study, with its cost and discomfort, if you don’t have data that an intervention is going to positively affect the child?" Dr. Ogle said.

A key piece of evidence that triggered the change in AAP recommendations was a Cochrane review of 11 studies totaling 1,148 children. The analysis concluded that correction of vesicoureteral reflux by surgery or medical interventions did not reduce the risk of renal scarring (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007 July 18;(3):CD001532).

The shift in the AAP guidelines has generated controversy among urologists, some of whom are in agreement with the change while others are opposed.

"I think for pediatricians, adopting these guidelines is an easy step," according to Dr. Ogle. "Many pediatricians in office practice had already adopted this years ago. They have not routinely done a VCUG on every child that presented with a febrile UTI. So for them, the impact of the 2011 Academy guidelines has been to say, ‘What you’ve been doing for the last 10 years is probably appropriate.’ "

He predicted that the current guidelines won’t be the final word on the topic of imaging in patients with febrile UTIs.

"What the guidelines don’t tell us is who exactly you should worry about. They don’t tell you which first-time UTIs you should consider VCUG in, and what’s the strategy for second-time UTIs. So stay tuned, there’s going to be further debate with regard to this, and hopefully further evidence," Dr. Ogle said.

"Remember," he continued, "the great history of American medicine is that first we adopt strategies for interventions in medical conditions, then we study them to see if our interventions are right."

Dr. Ogle reported having no relevant financial conflicts.