The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released new recommendations for screening for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection that include a one-time screening for everyone in the United States born between 1945 and 1965, regardless of risk.1 These new recommendations are an enhancement of, but not a replacement for, the recommendations for HCV screening made in 1998, which called for screening those at high risk.2

HCV causes considerable morbidity and mortality in this country. Approximately 17,000 new infections occurred in 2010.1 Between 2.7 and 3.9 million Americans (1%-1.5% of the population) are living with chronic HCV infection, and many do not know they are infected.1 This lack of awareness appears to be due to a failure of both health care providers to offer testing to those at known risk and patients to either acknowledge or recall past high-risk behaviors.

Those at highest risk for HCV infection are current or past users of illegal injected drugs and recipients of a blood transfusion before 1992 (when HCV screening of the blood supply was instituted). Other risk factors are listed in TABLE 1.1 Many of those with HCV infection do not report injection drug use or having received a transfusion prior to 1992, and they are not detected by current risk-based testing.

TABLE 1

Risk factors for HCV infection1

| Most common risks |

|

| Less common risks |

|

| HCV, hepatitis C virus |

Approximately three-fourths of those who acquire HCV are unable to clear the virus and become chronically infected.1 Twenty percent of these individuals will develop cirrhosis and 5% will die from an HCV-related liver disease, such as decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3

New treatments. In 2011, 2 protease inhibitor drugs, telaprevir and boceprevir, were approved for the treatment of HCV geno-type 1. These are the first generation of a class of drugs called direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs). When a DAA is added to the standard therapy of ribavirin and pegylated interferon, the rate of viral clearance increases (from 44% to 75% for telaprevir and from 38% to 63% for boceprevir).1 However, the adverse reactions caused by these new drugs can lead to a 34% rise in the rate at which patients stop treatment.1 Twenty potential new HCV antivirals are in clinical trials, and it is expected that treatment recommendations will change rapidly as some of these are approved.

Does treatment improve long-term outcomes?

Clinical guidelines recommend antiviral treatment for anyone with HCV infection and biopsy evidence of bridging fibrosis, septal fibrosis, or cirrhosis.4

A look at Tx and all-cause mortality. Studies looking at patient-oriented outcomes such as all-cause mortality and incidence of HCC have been conducted with pegylated interferon and ribavirin, without the newer DAAs. The most commonly cited study assessed all-cause mortality in a large sample of veterans with multiple comorbidities.

Those who achieved a sustained virological response after treatment exhibited a reduction in all-cause mortality >50% compared with nonresponders. This endpoint included substantially lower rates of liver-related deaths and cirrhosis complicated by ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy.5 However, in such a nonrandom clinical trial, an improved outcome for responders could be due to their relatively good health, with fewer comorbid conditions, and other undetected biases. While this study attempted to control for such biases, it didn’t provide evidence that treating infection detected by screening a low-risk population would improve intermediate or long-term outcomes.

Observational studies look at carcinoma incidence. Twelve observational studies have addressed treatment effects on HCC incidence. They showed a 75% reduction in HCC rates in those who achieved viral clearance compared with those who did not.1 Again, these studies did not compare treated and untreated patients in a controlled clinical trial; they looked only at treated individuals and compared the outcomes of responders and nonresponders.

HCV transmission research is lacking. The CDC found no studies in its evidence review that addressed the issue of HCV transmission. Nevertheless, the new recommendations state that HCV transmission was a critical factor in determining the strength of the recommendation for age cohort screening. It is expected that those who have a sustained viral response will be less likely to transmit the virus to others.

Why the 1945-1965 birth cohort?

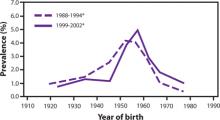

The prevalence of HCV infection in those born between 1945 and 1965 is 3.25%, and three-fourths of all those with HCV infection in the United States are in this cohort. The FIGURE depicts the large difference in prevalence between this age group and others. Within 3 cohorts defined by date of birth (1945-1965, 1950-1970, and 1945-1970), the prevalence of HCV infection is twice as high in men than in women, and in black non-Hispanics than in white non-Hispanics and Mexican Americans. However, extending the birth cohort to those born through 1970 yields only a marginal difference in prevalence figures. The CDC justifies restricting the new universal screening recommendation to the 1945-1965 age group mainly on the results of focus groups in which the public identified this cohort as “baby boomers” who would likely adopt the recommendation.

FIGURE

Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibody by year of birth1