The low specificity of the D-dimer assay poses another challenge to its effective use. There are many things that can increase D-dimer levels, such as age, cancer, prolonged immobility, autoimmune disease, inflammation, sickle cell disease, pregnancy, trauma, and surgery.13-15 All these factors must be taken into consideration prior to ordering this test.

In fact, one recent study found that using an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff (patient’s age in years x 10 mcg/L)—rather than a conventional cutoff of 500 mcg/L—for patients older than 50 years reduces false positives without substantially increasing false negatives.16

Also of note: An anticoagulant can decrease D-dimer levels in plasma, so the test should not be used to rule out PE or DVT in patients who are undergoing anticoagulation.13,15

THE TAKEAWAY: In evaluating patients for PE or DVT, use the Wells’ Criteria or Geneva Score (Revised) to determine a patient’s pretest probability of disease. Use the D-dimer assay to safely rule out these conditions in patients with a low or intermediate pretest probability, but go directly to scans for those with a high pretest probability.

3. Lipid panels: How important is fasting?

Patients are often instructed to report for fasting lab studies, specifically for lipid profiles. Traditionally, this had been defined as an 8- to 12-hour period without food.17 In clinical practice, however, this is often misinterpreted by patients, who may be confused about the duration of the fast or unsure about whether to eat or drink immediately before the test.

Studies investigating the effect of meals on lab values have found that triglycerides are consistently elevated postprandially, to a maximum of 12 hours.18-21 The effect of the fasting state on total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is more controversial; while some postprandial differences have been detected, the clinical relevance is equivocal.18-21

Nonfasting lipid values can offer useful information, particularly in patients who are unwilling or unable to return for fasting labs. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) supports this practice.22 Because guidelines for evaluation and treatment are based on fasting lipids, however, fasting lab work should be used, whenever possible, for initiating treatment and monitoring patients with abnormal values. If nonfasting lipids are used, it is crucial to factor in the postprandial effects on triglycerides and the subsequent difficulty of assessing LDL cholesterol levels.

THE TAKEAWAY: The clinical relevance of postprandial vs fasting lipid levels is equivocal. Nonfasting lipid panels have reasonable clinical utility in screening and initial treatment, particularly in cases in which obtaining fasting lab values may be problematic.18,19

4. Mononucleoosis spot test: When should you use it?

The monospot test is a latex assay that causes hemagglutination of horse RBCs in the presence of heterophile antibodies characteristic of infectious mononucleosis.23 The antibodies develop within the first 7 days of onset of symptoms, but do not peak for 2 to 5 weeks.24 As a result, monospot testing yields a high incidence of false negatives during the first 2 weeks of active infection.25 False negatives are also common in patients younger than 14 years. Heterophile antibodies may be present for up to a year after active infection.24

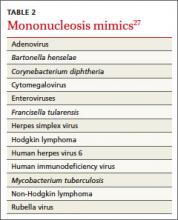

Patients at increased risk for splenic rupture, such as athletes, pose considerable diagnostic difficulty.26 When there is strong clinical suspicion of mononucleosis despite a negative monospot test in such high-risk individuals, follow-up testing is recommended to differentiate it from other mononucleosis-like illnesses (TABLE 2).27 The optimal combination of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serologic testing consists of the antibody titration of 4 markers: immunoglobulins M (IgM) and G (IgG) to the viral capsid antigen, IgM to the early antigen, and antibody to Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen (EBNA).28 Acute phase reactants in the setting of an antibody to EBNA could indicate reactivation. A positive test does not exclude other medical causes, however, because up to 20% of patients have acute phase antibodies that persist for years.29

Appropriate diagnosis is important because of the significant morbidity associated with EBV. Risk of splenic injury is greatest between 4 and 21 days after onset of symptoms but persists at 7 weeks,26 so conservative therapy followed by monospot retesting one week later is a reasonable approach.

Mononucleosis or routine tonsillitis? It is important to note that there is no evidence that a positive monospot test will affect the management or outcome of routine tonsillitis, raising questions of the utility of the test in such cases. A better approach: Reserve testing for patients with additional findings—ie, splenomegaly—or whose symptoms have persisted ≥ 2 weeks.