Investigators reviewed and conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies that encompassed more than 13,000 healthy adults and found a modest but significant association between T. gondii seropositivity and impaired performance on cognitive tests of processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive function. The average age of the persons in the studies was close to 50 years.

“Our findings show that T. gondii could have a negative but small effect on cognition,” study investigator Arjen Sutterland, MD, of the Amsterdam Neuroscience Research Institute and the Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 14, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Mental illness link

T. gondii is “an intracellular parasite that produces quiescent infection in approximately 30% of humans worldwide,” the authors wrote. The parasite that causes the infection not only settles in muscle and liver tissue but also can cross the blood-brain barrier and settle quiescently in brain tissue. It can be spread through contact with cat feces or by consuming contaminated meat.

Previous research has shown that neurocognitive changes associated with toxoplasmosis can occur in humans, and meta-analyses suggest an association with neuropsychiatric disorders. Some research has also tied T. gondii infection to increased motor vehicle crashes and suicide attempts.

Dr. Sutterland said he had been inspired by the work of E. Fuller Torrey and Bob Yolken, who proposed the connection between T. gondii and schizophrenia.

Some years ago, Dr. Sutterland and his group analyzed the mental health consequences of T. gondii infection and found “several interesting associations,” but they were unable to “rule out reverse causation – i.e., people with mental health disorders more often get these infections – as well as determine the impact on the population of this common infection.”

For the current study, the investigators analyzed studies that examined specifically cognitive functioning in otherwise healthy individuals in relation to T. gondii infection, “because reverse causation would be less likely in this population and a grasp of global impact would become more clear.”

The researchers conducted a literature search of studies conducted through June 7, 2019, that analyzed cognitive function among healthy participants for whom data on T. gondii seropositivity were available.

A total of 13 studies (n = 13,289 participants; mean age, 46.7 years; 49.6% male) were used in the review and meta-analysis. Some of the studies enrolled a healthy population sample; other studies compared participants with and those without psychiatric disorders. From these, the researchers extracted only the data concerning healthy participants.

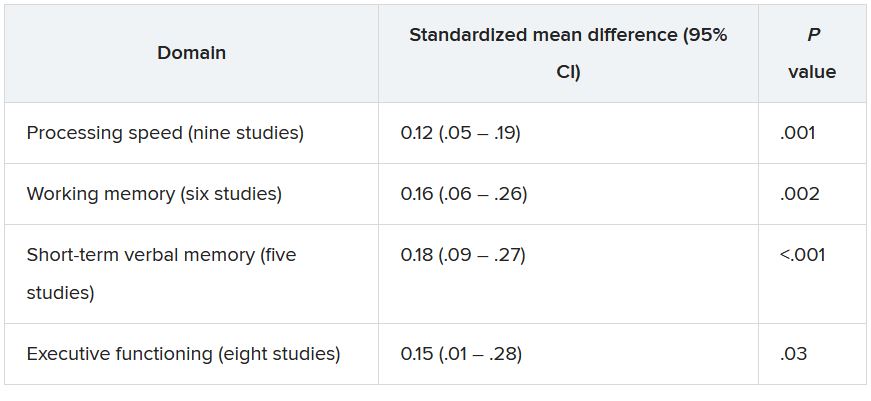

The studies analyzed four cognitive domains: processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive functioning.

All cognitive domains affected

Of all the participants, 22.6% had antibodies against T. gondii.

Participants who were seropositive for T. gondii had less favorable functioning in all cognitive domains, with “small but significant” differences.

The researchers conducted a meta-regression analysis of mean age in the analysis of executive functioning and found greater effect sizes as age increased (Q = 6.17; R2 = 81%; P = .01).

The studies were of “high quality,” and there was “little suggestion of publication bias was detected,” the authors noted.

“Although the extent of the associations was modest, the ubiquitous prevalence of the quiescent infection worldwide ... suggests that the consequences for cognitive function of the population as a whole may be substantial, although it is difficult to quantify the global impact,” they wrote.

They note that because the studies were cross-sectional in nature, causality cannot be established.

Nevertheless, Dr. Sutterland suggested several possible mechanisms through which T. gondii might affect neurocognition.

“We know the parasite forms cysts in the brain and can influence dopaminergic neurotransmission, which, in turn, affects neurocognition. Alternatively, it is also possible that the immune response to the infection in the brain causes cognitive impairment. This remains an important question to explore further,” he said.

He noted that clinicians can reassure patients who test positive for T. gondii that although the infection can have a negative impact on cognition, the effect is “small.”