MINNEAPOLIS – Neisseria gonorrhoeae is probing the final frontier of antimicrobial treatment.

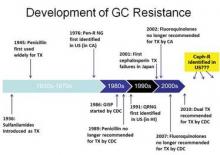

The persistent and versatile bacteria has proved its mettle against every antibiotic humans have thrown at it over the past 70 years, and now shows signs of figuring out the cephalosporins – the last bastion of effective antimicrobial treatment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have not seen any case of cephalosporin treatment failures in the United States yet. But researchers at the National STD Conference said it’s only a matter of time.

"We have already seen oral cephalosporin treatment failures in Asia and, in the last few years, in Europe," said Mark Pandori, Ph.D, of the San Francisco Department of Public Health. "None have yet been recorded in the U.S. but it’s wise to assume that it is on our doorstep, if not already here."

The bacteria developed fluoroquinolone resistance in the early 2000s, prompting CDC to drop that drug from its treatment recommendation in 2010. Now the agency recommends dual therapy: a 250-mg injection of ceftriaxone or a 400-mg dose of cefixeme, plus a 1-g dose of azithromycin or a 7-day course of doxycycline.

But now azithromycin resistance is becoming more common. Last July, the agency issued an alert about a cluster of five azithromycin-resistant isolates from a group of men who have sex with men (MSM) in San Diego.

In fact, one case of azithromycin treatment failure has occurred in the U.S., Olusegun Soge, Ph.D. reported at the meeting. After 12 days of treatment with the drug, the bacteria had already developed an increased resistance level, said Dr. Soge, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington, Seattle.

The patient was a 26-year-old MSM who received 2 grams of azithromycin. A culture showed a high level of azithromycin resistance. After 12 days of treatment, the patient was still experiencing symptoms consistent with a gonorrhea infection. He denied any sexual relations during treatment.

"We needed to know if this was a possible treatment failure, or a re-exposure," Dr. Soge said. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) determined that both isolates showed the same genetic blueprint, but the new specimen had an even higher resistance level: a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 8 mcg/mL compared to 0.5 mcg/mL in the first sample.

"The emergence of a resistant variant in an individual patient during treatment is alarming and may predict rapid emergence of gonococcal resistance," he said. He recommended that any patient who receives azithromycin as a single treatment should return for a test of cure.

At this point, cephalosporins are really the only treatment with certain effectiveness, said Dr. Sarah Guerry, medical director, of the sexually transmitted disease program at the Los Angeles County Public Health. "Not only have we had to increase the recommended dosage of ceftriaxone, but now this is our therapy of last resort," she said at the meeting.

Many STD clinics, however, are only able to distribute oral medications. Dr. Guerry and her colleagues examined whether complying with the new treatment recommendations of intramuscular ceftriaxone was delaying treatment.

She reviewed all urogenital and anorectal gonorrhea cases diagnosed in Los Angeles County from April-August 2010 – before the new treatment guidelines – and from the same period in 2011. The review focused on clinics that treated less than 10% of cases with any dose of ceftriaxone injection, and compared the overall and median time to treatment, as well as compliance with the new recommendations.

There were 508 gonorrhea cases in 2010 and 401 in 2011. Overall, 11% of the clinics surveyed were considered "low injectors."

Almost three-fourths of the clinics (72%) dispensed some form of the treatment recommended for that period. This did not change after the new guidelines came out, indicating that most clinics adopted the new guideline. But in 2010, only 13% of the facilities were giving the injected ceftriaxone. In 2011, there was a dramatic change, with 90% of the facilities giving the injection.

Time to treatment, however, was not significantly altered, indicating that switching to the injected form did not delay treatment. Overall, the time from diagnosis to treatment increased from 5 to 7 days.

Still, there is plenty of room for improvement in delivering the recommended treatment, according to Roxanne Kerani, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at the Seattle and King County Public Health Department, Wash. She collaborated with CDC researchers to estimate how frequently clinicians across the country are delivering treatment according to the new CDC guidelines. They polled clinics included in the national STD Surveillance Network: Washington, California, Colorado, Baltimore, and San Francisco.