ESTES PARK, COLO. – The most important thing to know about the current American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis is that they are primarily a research tool and should only be applied diagnostically in selected circumstances.

The current criteria, known as the 2010 criteria, are markedly more effective at detecting RA early on – when it is far more treatment-responsive – than were the former 1987 criteria. That’s the upside. The downside of the 2010 criteria is unless they are employed judiciously, many patients will be inappropriately labeled as having RA and subjected to treatments they don’t actually need, Dr. Jason Kolfenbach explained at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Two essential preconditions must be met before the 2010 criteria can appropriately be brought to bear in diagnosing RA in the clinic. First, the patient has to have at least one swollen joint; joint pain without swelling isn’t sufficient.

Second, any alternative diagnoses that might better explain an individual’s synovitis must first be ruled out. It has been demonstrated that if the 2010 RA criteria are applied without first ruling out conditions including gout, lupus, and sarcoid, the false-positive rate, even in rheumatologists’ hands, is roughly 20%. When rheumatologists took the time to first remove the cases they thought likely to be something other than RA, however, the false-positive rate using the 2010 criteria fell to 9%, noted Dr. Kolfenbach, a rheumatologist at the university.

And then there’s the whole squirrelly matter of transient joint swelling.

Among patients with one or more swollen joints and no obvious etiology for their arthritis, the spontaneous remission rate approaches 50%. But among the subset of patients with at least one swollen joint who fulfill the 2010 criteria, the spontaneous remission rate appears to be much lower, on the order of 10% (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:389-93).

The 1987 criteria required radiographic evidence of erosions as well as the presence of subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules. Those are highly specific features of long-standing RA, but they’re not helpful in identifying patients with early disease. The impetus for developing the 2010 criteria was a persuasive body of evidence that in order to maximize outcomes physicians need to intervene earlier in the disease process than was possible using the 1987 criteria.

"The window for intervention is actually quite small. If you delay more than 3 or 4 months after symptom onset, your response to disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy is worse," he said.

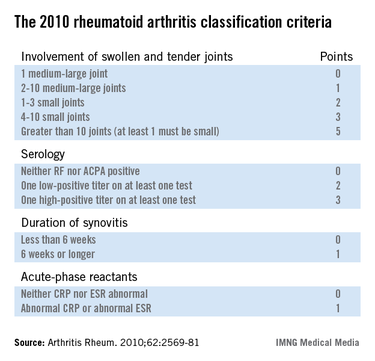

The 2010 criteria (Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569-81) were developed through longitudinal follow-up of a cohort of patients who presented with an inflammatory arthritis that didn’t meet the 1987 criteria for RA. Investigators looked for features present initially that helped predict later definite RA. They found four: inflammatory joint involvement; antibody status; duration of synovitis; and the presence of inflammatory mediators, also known as acute phase reactants. Under the 2010 criteria, a score of 6 or more out of a possible 10 based upon these four elements is deemed definite RA. Of note, erosions and rheumatoid nodules aren’t part of the current diagnostic criteria.

Dr. Kolfenbach noted that in a large Dutch study, the sensitivity of the 2010 criteria for the diagnosis of RA as defined by the use of methotrexate or any other disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy within the first year of follow-up was 84%, an impressive absolute 23% improvement over the 61% sensitivity using the outmoded 1987 criteria (Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:37-42).

"The problem, like with any test, is if we improve sensitivity it reduces specificity – and that increases the probability of inappropriately labeling someone as having rheumatoid arthritis," he observed.

Indeed, the Dutch study also showed that the diagnostic specificity of the 2010 criteria was only 60%, down from 74% when the 1987 criteria were applied to the same population.

So what’s the smart way to apply the 2010 classification criteria for RA?

"Clinical history and the physical exam are still king. If a patient comes through your office door with polyarticular swelling, mostly in the fingers and wrists, and it’s symmetrical, with a lack of systemic organ disease, that’s a person at much higher risk of having rheumatoid arthritis. It’s really reasonable then to apply the 2010 criteria and test for serologic antibodies and inflammatory markers. And if those are positive, then you’ve really cemented your feeling that this person very likely has rheumatoid arthritis," according to Dr. Kolfenbach.

Under the 2010 criteria, antibody testing remains "hugely important" in establishing the diagnosis of RA, he continued.