Abstract

- Objective: To describe Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and its application in the treatment of chronic pain.

- Methods: Review of the theoretical and clinical literature and presentation of a case example.

- Results: General cognitive behavioral approaches for chronic pain have a consistent and large evidence base supporting their benefits. Even so, these treatments continue to develop with the aim to improve. One example of a relatively new development within the cognitive behavioral approaches is ACT, a treatment that focuses on increasing psychological flexibility. Here we describe ACT and the therapeutic model on which it is based, present its distinguishing features, and summarize the evidence for it as a treatment for chronic pain. We also discuss such issues as dissemination, implementation, and training.

- Conclusion: There are now 7 randomized controlled trials, a number of innovative uncontrolled trials, and at least 1 systematic review that support the clinical efficacy and effectiveness of ACT for chronic pain. Further research and development of this approach is underway.

The introduction of the gate control theory of pain [1] in 1965, among other events, signaled a shift in our understanding of pain, particularly chronic pain. This shift, which continues today, is a shift from a predominantly biomedical model of chronic pain to a biospsychosocial model. This model, as the name suggests, includes psycho-social influences in a key role in relation to the experience of pain and the impact of this experience. During this same period of time, psychosocial models and treatment methods have also shifted and evolved. This evolution has included the operant approach [2], the cognitive behavioral approach [3], and the latest developments, contextual cognitive behavioral approaches [4,5], among which Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based therapies are key examples.

Until about 10 years ago, the mainstream of psycho-logical treatments for chronic pain and other physical health problems was dominated almost exclusively by concepts and methods of what we will refer to as “traditional” cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Specific constructs within what is called the “common sense model” [6], such as illness perceptions, beliefs about control over one’s illness, amongst other constructs such as self-efficacy, catastrophising, fear avoidance, and pain-related anxiety, captured a substantial focus of research and treatment development during most of the past 3 decades [7]. The treatment methods that have emerged and persisted from this work have included relaxation, attention-based and cognitive coping strategies, cognitive restructuring, the use of imagery, and certain activity management strategies [8]. However, despite consistent supportive evidence for CBT interventions for chronic pain [9], there remain gaps and areas of relative weakness, both in the conceptual models underlying this work and in the base of evidence. Research clearly shows that not all patients benefit from traditional CBT interventions, and recent reviews of CBT for chronic pain generally show effect sizes that are usually small or mediumat best [9–11].

The Problem with Pain

Pain hurts and is often viewed as harmful, and this leads to fear or anxiety, avoidance, or attempts to control the pain. Seeking to control pain is entirely natural and even seems necessary to reduce the undesirable effects of pain in one’s life.

Dependent on the situation, pain avoidance, sometimes also referred to as “fear avoidance,” in studies of chronic pain can present itself in many forms. Avoidance behavior can include refusal to engage in any activity believed to cause an increase in pain. It may also include “guarding” or bracing around an area of pain, information seeking, treatment seeking, taking medications, overdosing on medications, using aids like heat or ice, withdrawing from social activity, as well as being unwilling to talk about emotional experiences, amongst others [5]. Today, avoidance is recognized as a key foundation element in pain-related suffering and disability [12], and addressing it effectively has become a prime focus in many or most current treatments.

Acceptance and Psychological Flexibility

In recent years, the concept of “acceptance” has gained prominence as a potentially important process for addressing a broad array of psychological problems, including those associated with chronic pain. From this new interest, a fundamentally different treatment emphasis has emerged. This includes a shift away from a predominant focus on changing thoughts and feelings, a focus sometimes adopted within some traditional CBT methods, towards a focus on reducing the influence of thoughts and feelings on our actions instead. This can be a rather confusing distinction. This is because the influence of our thoughts and feelings is often automatic and even invisible to us as it occurs. As such, the influences of our thoughts and feelings appear directly tied to the content of thoughts and feelings, but the matter is not that simple. Clearly there are occasions when our actions contradict our thoughts and feelings, such as when we have perfectly confident beliefs and fail, or significant anxiety and perform successfully. Such instances illustrate what we might call a “2-dimensional” quality of experience; it is the content of experience and the context of experience that determine the influence exerted. Suffice it to say acceptance-based methods are designed to address the difference between experiences that are difficult to control, such as thoughts and feelings, and things that are easier to control: the actions we take in relation to our thoughts and feelings. They do this by taking a focus on creating changes in context and ultimately in behavior. Acceptance includes especially a focus on allowing or opening up to feelings rather than struggling with them or retreating from them. Here, the capacity for openness is a contextual process.

Acceptance methods are not used in isolation. They are usually used in combination with other traditional behavior change strategies, with methods to facilitate values clarification, committed action, and other methods from ACT. Notions of acceptance have even been incorporated into many behavioral and cognitive therapies before, including dialectical behavior therapy [13] and mindfulness-based treatment [14,15], and so this process is not the exclusive domain of ACT. In implementing acceptance-based methods, patients are taught skills, such as to (a) notice feelings specifically in detail, (b) notice that thoughts about pain are products of thinking and not the same as direct experience, (c) notice urges to struggle with thoughts and feelings, (d) to practice refraining from struggling and adopt an observing, allowing, and “making room”–type posture, and (e) take action in line with their goals [4,5].

The wider processes around acceptance in combination are referred to as psychological flexibility [16]. Psychological flexibility relates to one’s ability to directly contact the present moment; to be aware of the thoughts, feelings and potentially unwanted internal experiences it brings; and to follow through with a behavior change or persist with a chosen behavior in the direction of chosen values. Psychological flexibility is the model for psychological health from an ACT perspective [17].

Psychological Flexibility and the 6 Core ACT Processes

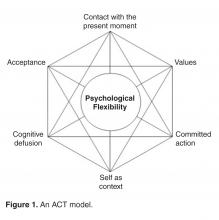

At least some of the core processes of ACT have been mentioned already. They are unusual enough for most readers so that a more careful definition of each can be useful. At the core of ACT is the concept of psychological flexibility. Again, psychological flexibility is one’s ability to effectively respond and make behavior changes according to one’s personal goals and values while poten-tially interfering thoughts and feelings are occurring, and without being blocked by those thoughts and feelings [18]. Psychological flexibility is enhanced through a focus on 6 core ACT processes, namely Acceptance, Cognitive Defusion, Present Moment Awareness, Self as Context, Values, and Commited Action [4], in no particular order. The interrelations between these processes are depicted in Figure 1 .Acceptance

Acceptance involves the patients’ willingness to have pain while remaining able to actively choose to continue participating in their life as they want it to be. ACT encour-ages patients to act in ways that are consistent with direct experiences rather than what the mind interprets these events to mean.

Cognitive Defusion

Cognitive defusion is the process of modifying one’s reaction to thoughts by constructing contexts where the influences of these thoughts on behavior are lessened [18]. Unlike traditional cognitive behavior approaches, in ACT it is not the content and actual validity of these thoughts that is challenged but the functions, or influences, of thoughts [19].

Present Moment Awareness

Contact with the present moment reflects the process wherein the person is aware of the situation in “the now” as opposed to focusing on events that happened in the past or might happen in the future [18]. To be “present” requires the individual to flexibly focus attention on experiences as they are happening in the environment, in real time, and to be fully open to what is taking place [20]. It is important the individual is able to notice when he or she is not acting in relation to the present moment and has the ability to shift attention to the present if this shift benefits them.

Self as Context

The sense of self-as-context or self-as-observer is considered the ability to adopt a perspective or point of view that is separate from and not defined by thoughts and feelings or even the physical body. This contrasts a sense of self as made up of personality characteristics, self-evaluations, or a narrative about who we are [5,16]. In ACT, perspective taking can be trained to help people connect with the experience of a distinction between self and psychological experiences. From this, one can choose to follow one’s inner verbal constructions of what defines us, our “stories” of who we are, in certain situations when it works to do so, and not in situations where it leads to unhealthy responses and behavioral restriction.

Values

Values are defined as guiding principles in one’s life. Values are often contrasted with goals, where the difference is that goals can be achieved while values are part of an ongoing process of action and cannot be completed once and for all. In a sense, goals represent set plans of action to be achieved while values are general life directions. If life is like a journey, then goals would be the chosen destination and values would simply be represented by a general direction of travel. Values are helpful when patients struggle with unwanted internal experiences like pain, as they not only serve as a guide for the client to persist in behavior change but also function as a motivating element. Values clarification exercise in therapy encourages the patient to define their values in specific domains of “career, family, intimate relationships, friendships, health, education and spirituality” [4,21] regardless of the primary problem. Personally chosen and clarified values can function as guides when people have difficulty initiating and maintaining behavior change in the presence of unwanted internal experiences.

Committed Action

Committed action is an ongoing process of redirecting behavior in order to create patterns of flexible and effective action in line with a defined value [22]. Patients are encouraged to follow through with their chosen actions that are in line with their values, and to persist or alter their course flexibly. Without the capacity for committed action, behavior change is less likely to persist and integrate into patterns of behavior more generally.

The 6 core processes of ACT in combination are designed to serve the purpose of better functioning. They are the focus of ACT methods but not an end in themselves. This “process” and “outcome” distinction is an important one in ACT. The main focus of ACT is to enhance activity and function through an increase in psychological flexibility. Unlike many psychological therapies, ACT does not aim for symptom reduction as a primary therapeutic goal. Figure 2 pictorially depicts psychologically flexible behavior.Case Study

Initial Presentation and History

Ms X, a 45-year-old woman, presents with the chief complaint of low back pain, which she has experienced for 3 years. She works part-time due to her pain problem. When she is not at work, she busies herself with seeking both conventional and alternative treatments for her pain condition. In the past, during periods where she experienced pain relief, she attempted to engage in her hobby of photography. However, this often led to a pain flare the next day and required 2 to 3 days of medical leave with increased medication from her PCP before she is able to return to work. As a result, Ms X chose to give up her hobby and focus on treating her pain instead. Ms X in in a constant struggle with her pain condition and believes that she can only return to photography, and live a more normal life, after her pain is cured.

• What are considerations for applying ACT in this scenario?

From an ACT conceptualization this case shows patterns of avoidance that are apparently not helping the person to reach her goals but are causing her distress and restrictions in functioning. An ACT therapist would approach this scenario by first reflecting how normal it is to struggle with pain and stop activities when in pain. From there they might (a) identify what the patient wants from treatment, (b) look at what has been done so far to attain this, (c) examine how well those things have been working, (d) consider the costs of the approach being taken, and (e) if the approach is not working and the cost is high, see if the patient is willing to stop this approach [23].

Therapist’s Initial Approach

Therapist: By what you have told me, your pain has become a big problem for you and it has been going on a long time—3 years. I can see some of the impacts it has had in your life, such as on your work, your photography, and time spent seeking treatment.

Ms X: Yes, it seems like pain has taken over …

Therapist: Exactly, it seems that is a good way to say it. So, understanding that pain has taken over, can I ask you another question?

Ms X: If your question will help me get over this problem, of course.

Therapist: Ok. What is it you want from coming here to participate in this treatment?

Ms X: Well, I want to get rid of this pain, obviously. It’s ruining my life.

Therapist: Ah, that makes sense. You want to eliminate your pain because it has, as you say, ruined your life, and then I guess your life will be better again.

Ms X: Correct.

Therapist: So, can I check in with the things you have been doing so far to reach this goal to eliminate pain?

Ms X: You name it, I’ve tried it: acupuncture, medication, herbs, rest, exercise, magnets, yoga, and more.

Therapist: Ok, you have tried many treatments focused on trying to get rid of the pain. I think that’s a very natural thing to do. In your experience have these methods been successful?

Ms X: Well, some of them seem to work at the time but it all becomes very confusing, because here I am looking for another treatment. It can feel good to get away from the pain for a little while, but soon I will experience a pain flare bringing me back to square one.

Therapist: I see what you are saying. Let me ask my earlier question in a different way. What would your life look like, and what would you be doing, if your pain were not the problem it is today?

Ms X: I would be taking pictures again, be more consistent at work, and spend less time seeking treatments.

Therapist: So, is it your experience that the methods you have been using have helped you to live life this way?

Ms X: … I never thought about it that way ...

• What exercises or techniques are used in ACT?

In practice, ACT is somewhat unique in that it often relies on the use of metaphors and experiential exercises in treatment delivery. Metaphors and stories are used in treatment and communicated in terms that fit with the experience and background of the person seeking treatment. Although therapists can select from among many widely used and often appropriate metaphors and stories, an experienced therapist is likely to create patient specific metaphors “live,” within the context of a particular session. This is consistent with the philosophical underpinning of ACT in its aims for individual tailoring of methods. Unlike other current psychotherapeutic approaches that place a higher value on sticking to a specified protocol, the theory and philosophy behind ACT allow for flexibility and are open to creativity, individual style, and situational sensitivity of the therapist. This is expected to allow the patient to also adopt a similar sensitivity to changing environmental contingencies [19]. In ACT, the techniques typically do not follow a cookbook style of treatment delivery.

Case Continued

Therapist: What if trying to control your thoughts and feelings were not the answer?

Ms X: I have no idea what you mean.

Therapist: Well, you certainly have focused a lot of your effort on trying not to have the thoughts and feelings that seem to block you.

Ms X: What else is there to do, really?

Therapist: If you are willing to experiment with something, try this. Don’t think of a pineapple. (pause for 30 to 60 seconds). Ok, what happens.

Ms X: It didn’t work—I kept thinking about a pineapple.

Therapist: Weird, huh? Notice what is happening here. I wonder if some of your struggles with your experiences are just like this. It’s like by trying to get rid of something, there it is! I wonder if there were another way to do this, do you think you might be willing to test it out?

Ms X: Yes, I can try.

Further ACT Methods

ACT includes numerous experience-based methods and also direct rehearsal of targeted skills. In the previous scen-ario, the therapist might then proceed to instruction and practice of one or another type of acceptance-based skill, something like an “exposure” session or a mindfulness type of exercise that includes having the participant sit with the experience without doing anything else but observe it. The other type of method used includes metaphors that reveal how circumstances and behavior often work in life [4,16].

An Acceptance-Based Metaphor

Therapist: Imagine that you are new to the neighborhood and you invited all your neighbors over to a housewarming party. Everyone in the neighborhood is invited. On that day, the party’s going great, and here comes Joe, who smells and looks like he has not bathed in days. You are embarrassed by the way he looks and smells and try to close the door on him. However, he shows you a flyer that you put up stating that everyone in the neighborhood is invited. So you let him in and quickly shove him to the kitchen so that he will not embarrass you and disrupt your party. However, to stop him from leaving the kitchen, you end up having to stand guard at the doorway. Meanwhile the party is going on and your guests are enjoying themselves, but do you notice what else is happening here?

Ms X: I’ve stopped myself from enjoying my party in order to keep Joe away.

Therapist: What if your pain was like Joe?

Ms X: Huh? … Ah, I think I see what you are saying…

Therapist: It’s like if you allow Joe to simply be another guest, you can do whatever you like at your party. On the other hand, if you say “no” to Joe you also say “no” to the party.

Ms X: Are you saying that it is for me to choose?

• What is the role of therapist in modeling behavior change in ACT?

An important distinction can be made between talking about behavior change and doing behavior change. Within the psychological flexibility model the emphasis is placed on the latter. Here, especially through the use of experiential exercises, clients are put into contact with the experiences that have coordinated unhealthy behavior patterns in the past so that more effective behavior patterns can be acquired. Treatment delivery is guided by the underlying behavioral philosophy and theory. Patients learn to reduce the dominant influence of the literal meaning of language as the only tool for behavior change. Direct experience is moved to the front of awareness and literal meaning, mental and verbal analysis, and so forth, are moved to the back [20]. In treatment, the therapist models for the patient the behavior change processes that are being targeted and also may use examples from his or her life as well as that of the patient’s to develop psychological flexibility [22]. An example might include a therapist’s response to a person who shows an experience of emotional distress and struggling to manage this distress. Here the therapist, in line with ACT, instead of acting in some way to attempt to lessen the distress, would consciously show openness to the experiences and to their own reactions to helplessness around these experiences.

The therapist might say:

“I would feel tired and probably in pain too if I did what you just did. Could we do a little closed-eyes exercise? Shall we put the distressing thought you are having on the table, and focus on it, and we can “observe” what your mind does, and what happens in your body and your emotions when that thought shows up? Are you willing?”

“I’m feeling confused about this issue myself - how about both of us sitting quietly for a moment or two and observe what our minds do in response to this, just slowing things down, and watching?”

“I feel anxious when I believe that my thoughts about pain are true - like I have to do something to make it go away but I don’t know how. What shows up for you when you believe such thoughts about pain?”

• How and when should ACT be used?

Based on current evidence how and when ACT ought to be used, as opposed to other treatment options, will be largely up to the individual professional and their level of competence. ACT is a form of CBT and many of the same guides pertain. In line with the pragmatic approach of ACT, an approach that makes ACT broadly applicable, there is no one particular manualised or scripted treatment protocol that must be adhered to in treatment for one specific condition or another. As mentioned earlier, the ACT approach does not usually follow a cookbook style of delivery, nor is it rigidly guided by strict protocols. There are protocols shared by researchers to support further development but there is no process by which these are deemed “official” or “recognized” or approved by anyone in particular.

A wide range of metaphors and exercises based on a set of behavioral principles that target a particular function has been proposed in ACT and this is part of its uniqueness as a therapeutic model.

Those developing ACT also have not required a standardised certification process to delivering ACT. Instead, they have chosen to create an open community of contributing researchers and clinicians who are “members” by virtue of their commitment to the same approach to clinical development and the same clinical model. Practicing ACT requires that the clinician is aware of their own competencies and delivers treatment accordingly.

• How effective is ACT?

Numerous studies have supported a general role of psychological flexibility in improving the well-being and physical functioning of patients with chronic pain, including patients in specialty care [24,28] and primary care [26]. Many studies support the particular role of acceptance of pain in adjustment to chronic pain [27–30]. Pain acceptance is a better predictor of outcomes than pain severity itself [31,32].

There are now several relatively large-scale studies conducted in actual clinical practice settings that demonstrate the effectiveness of ACT for chronic pain [25,27,33,34]. A more recent study, also conducted in an actual clinical practice setting, provided support for the specific treatment processes proposed within this approach [35]. This study showed that changes in traditionally conceived methods of pain management were unrelated to treatment improvements of pain intensity, physical disability, anxiety and depression for those who participated in treatment, while changes in psychological flexibility were consistently and significantly related to these improvements, with the exception of the results for depression.

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs)

To date, there are a total of 7 RCTs related to ACT and chronic pain [36–42], each providing supportive evidence. For example, in one of the early studies, Dahl and colleagues [36] showed that in comparison to treatment as usual, a group of workers who were at risk of long-term absenteeism from work due to pain or stress had a significant reduction in sick leave and healthcare usage after attending four hours of ACT sessions.

Wicksell and colleagues [37,38] conducted 2 separate RCTs with participants who suffered whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) and fibromyalgia, respectively. Post-treatment results of both RCTs showed an improvement in physical functioning, depression and psychological flexibility in the treatment group with gains maintained at follow-up. In addition, participants in the treatment group with WAD showed an improvement in life satisfaction and fear of movement while those in the treatment group with fibromyalgia showed significant improvements in fibromyalgia impact, self-efficacy and anxiety. There was however no change in pain intensity in those who received the ACT-based treatments.

An ACT-based treatment including a self-help manual showed a significant increase in acceptance, satisfaction in life with a higher level of function and decreased pain intensity compared with a wait-list condition and with applied relaxation (AR) [40]. In comparison to the AR condition, participants in the ACT condition also reported a significantly higher level of engagement in meaningful activities and a willingness to experience pain. Follow-up data support the maintenance of these improvements at first follow-up but differences were not significant at the second follow-up. Both depression and anxiety scores improved in both treatment groups.

Wetherell and colleagues [39] compared the effectiveness of ACT and traditional CBT and found that they both produced positive results. Results from the study also showed higher satisfaction in participants who attended ACT treatment than those that attended CBT treatment, suggesting that ACT “is an effective and acceptable” intervention for patients with chronic pain. Overall acceptance of pain was shown to differentiate patients who could function well with chronic pain from those that continued to suffer with it after treatment.

More recently the first internet-based RCT for ACT with chronic pain was conducted [41]. The authors found a reduction in measures of pain-related distress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety, with these gains maintained at 6 months follow-up in the ACT treatment group compared with controls. The most recent RCT was a pilot trial of a group-based treatment of people with chronic pain recruited from general practices in the UK [42]. Participants were randomised to either an ACT-based treatment or treatment as usual. Participants in the ACT-based group underwent 4 sessions each lasting 4 hours with the first 3 sessions completed in 1 week and the last session completed a week later. At 3 months follow-up, participants in the ACT group had lower disability, depression, and higher pain acceptance.

In general, results from the ACT-based RCTs on chronic pain support the efficacy of the treatment and reflect a high degree of versatility, based on the wide variety of modes of delivery tested. However, RCTs for chronic pain are still relatively few with some studies limited to small sample sizes, thus making it difficult to reach definitive conclusions on the general efficacy of ACT in chronic pain treatment. What the studies do seem to show is that ACT is a good alternative treatment option to more traditionally conceived current CBT-based treatments for chronic pain. Larger sample sizes and higher quality studies are needed to strengthen and establish the effectiveness of ACT and to understand the potential impact of wider implementation in clinical practice.

Meta-Analyses

A total of 4 meta-analyses [43–46] have been conducted on acceptance- or ACT-based treatment studies. Although the earlier meta-analyses [43,44] did not separately report the effectiveness of ACT for chronic pain, they reported a moderate effect size for ACT in general, with no evidence that ACT is more effective than established treatments.

Ruiz [46] conducted a review focusing on outcome or mediation/moderation type studies that compared ACT and CBT treatments. His review was not specific to chronic pain, although one study [39] involving a sample of chronic pain patients was included. Moderate effect sizes were found that favored ACT, with ACT showing a greater impact on change processes ( g = 0.38) compared to no impact found in CBT ( g = 0.05).

Essentially, only one meta-analysis [45] specifically reviewed the efficacy in chronic pain studies. Pain inten-sity and depression were selected as primary outcome measures, with anxiety, physical well-being, and quality of life selected as secondary outcomes. Out of 22 studies that were included in the review, only 2 studies [36,37] were ACT-based RCTs, with the rest of the studies mindfulness-based interventions. The overall effect size of 0.37 was found for pain and 0.32 for depression. In general, results showed significant effect sizes for both primary and secondary outcome measures in favor of the “acceptance-based treatments.” The authors concluded that at present, mindfulness-based stress reduction programs and ACT-based programs may not be superior to CBT but could be good alternatives for people with chronic pain.

The appropriateness of using pain intensity as a primary outcome measure for ACT-based studies is questionable [45]. The focus of ACT is to increase function rather than to reduce pain symptoms; hence possibly including interference of pain in daily life might be a more appropriate outcome measure.

Other Studies

A particularly important question to answer about ACT concerns its cost-effectivness, and we still know relatively little about this. We do know that when people participate in ACT-based treatments they are able to reduce medication use and health care visits and return to work after extended periods away from work [27,28]. It remains to conduct full health economic analyses of this type of approach for chronic pain.

ACT is known to produce significant benefits widely, in other applications apart from chronic pain, such as in workplace stress [47], psychosis [48], obsessive-compulsive disorder [49], and depression [50], among other mental health conditions [51].

• What are implications for policy makers?

Results from studies of ACT in chronic pain and in other areas are disseminating rapidly. This dissemination is aided in part by a professional organization devoted to ACT and psychological flexibility (Association for Contextual Behavioral Science; www.contextualscience.org), which has a new journal, the Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science , started in 2012.

With the development of ACT a focus on implementation, training, and treatment integrity began early. There was an implementation study of ACT was published by Strosahl and colleagues in 1998. Their study showed that training clinicians in ACT produced better outcomes and better treatment completion rates in an outpatient setting in comparison to clinicians not receiving this training.

Processes of training have also appeared during relatively early phases of research into ACT. Lappalainen and colleagues [52] compared the impact of treatment provided by trainee therapists trained in both a traditional CBT model and ACT. Here each trainee therapist treated one patient with traditional CBT and one with ACT. Although the therapists reported higher confidence in delivering traditional CBT, patients treated within an ACT model showed better symptoms improvement. Also, improved acceptance during treatment significantly predicted improvements across both groups of patients. Essentially, therapists with only a limited amount of training in both models demonstrated better clinical results with ACT.

A group-based ACT intervention has also been shown to be effective in reducing stress and improving the professional performance of clinical psychology trainees [53]. Here the trainees found the intervention personally and professionally useful and a majority showed a significant increase in psychological flexibility. This supports the applicability of ACT not only as a model to guide therapy but also as a model to guide training and professional performance [54]. Other results in a pain management setting show that transitioning to ACT as a treatment model can have similar benefits and may increase job satisfaction and staff well-

being [55].

• What are criticisms of ACT?

Many strong supporters of cognitive therapy and more traditional versions of CBT in the field claim that ACT is not new nor better than other current versions of CBT [56]. The proponents of ACT openly acknowledge that many methods used within ACT are adopted or modified from other established therapies [4]. Criticisms are not specific to the application of ACT with chronic pain but are based on others’ perceptions of ACT as a treatment approach and treatment techniques used in ACT in general.

Ost [43] criticised ACT and the third-wave therapies on 2 main grounds. First, he concluded that ACT and the rest of the third-wave therapies were not meeting the criteria of empirically supported treatments. He further concluded that there is no strong evidence to show that ACT is more effective than cognitive therapy. The methods of the Ost review have been challenged [57], yet to a certain degree the points raised are correct. Most of the limitations noted reflect a difference in the maturity of the evidence base for ACT versus traditional CBT-based approaches. Indeed, in comparison to CBT, which is the most empirically established form of psychotherapy and an active area of research for more than 40 years, ACT can be considered to be in its infancy stage of empirically supported treatments, where treatment evidence and availability of high-quality RCTs in general are few at present. Specific research on ACT for chronic pain though supportive is still preliminary to a certain degree. Even so, ACT for pain is regarded as an empirically supported treatment by the body within the American Psychological Association authorized to make this determination [58].

Conclusion

ACT is essentially a form of CBT, considered broadly. ACT brings with it a different philosophy and approach to science compared with some other forms of CBT—this can lead to some distinctive strategies and methods in treatment for chronic pain. Like traditionally designed CBT, however, ACT similarly aims for behavior change as the end point.

ACT is grounded in specific philosophical assumptions and includes the model of psychological flexibility at its core. Preliminary findings in broad clinical and nonclinical populations support the efficacy, effectiveness, and processes in the psychological flexibility model as mediators of change, in ACT [46,59]. Research has shown that most of the 6 ACT processes, all of those so far investigated, correlate with improved daily functioning and emotional well-being in patients with chronic pain. The evidence base for ACT is still developing. Larger trials, more carefully designed trials, and a continued focus on processes of change will be needed to strengthen this base.

Corresponding author: Su-Yin Yang, Health Psychology Section, Psychology Department, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, 5th Fl, Bermondsey Wing, Guy’s Campus, London SE1 9RT, su-yin.yang@kcl.ac.uk.

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, SY, LMM; analysis and interpretation of data, SY; drafting of article, SY, LMM; critical revision of the article, LMM; administrative or technical support, LMM; collection and assembly of data, SY.