Laboratory testing

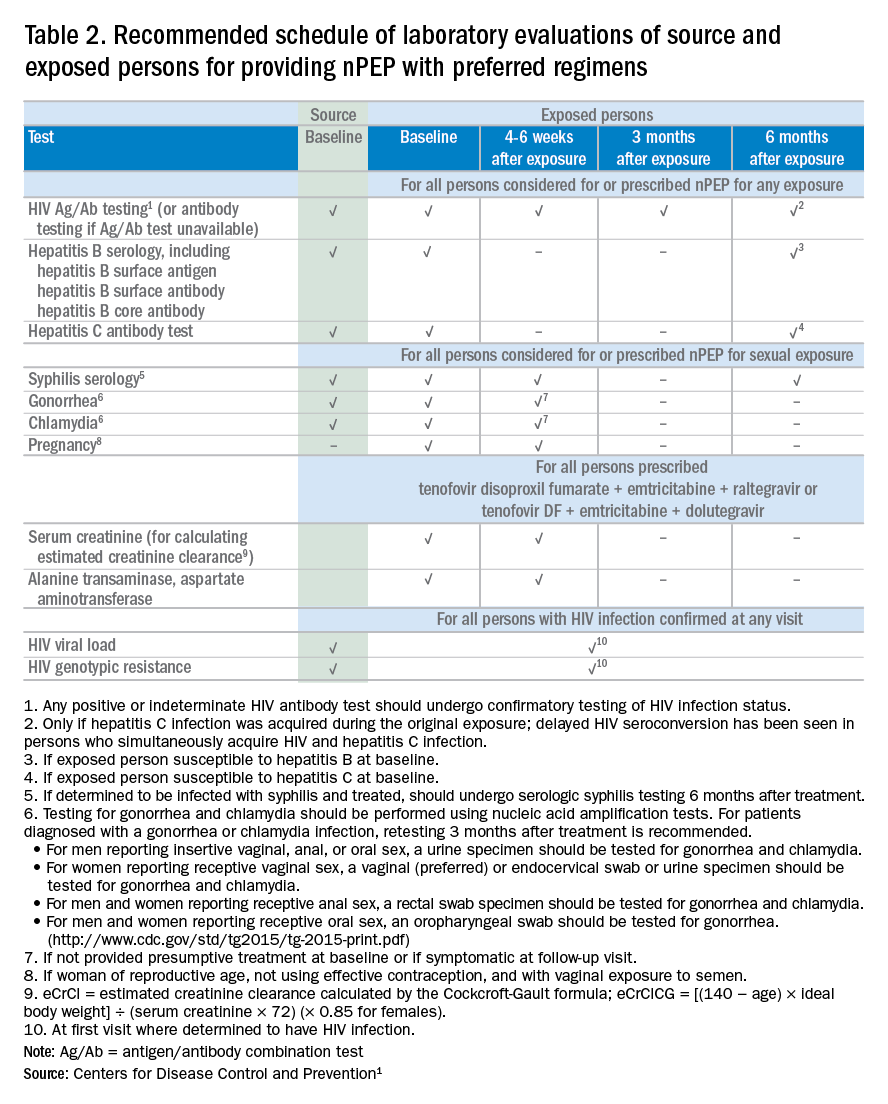

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

The availability of PEP drug regimens that can reduce HIV transmission after a possible acute HIV exposure is an important tool in the portfolio of HIV prevention strategies, which also include HIV screening, condom use, PrEP, and antiretroviral therapy for HIV-positive persons. Primary care providers play a critical role in rapidly evaluating patients appropriate for nPEP and initiating treatment within 72 hours of possible exposure. For patients evaluated and put on a course of nPEP outside of the primary care setting (for example, in an ED or urgent care), primary care physicians should work to achieve optimal communication and collaboration to ensure that they are best prepared to provide their patients with the necessary follow-up testing, counseling, and medical care.Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.