CASE PRESENTATION

A 61-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis C and hypertension presents to his primary care physician due to right upper quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation shows transaminases elevated 2 times the upper limit of normal. This leads to an ultrasound and follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Imaging shows diffuse cirrhotic changes, with a 6-cm, well-circumscribed lesion within the left lobe of the liver that shows rapid arterial enhancement with venous washout. These vascular characteristics are consistent with HCC. In addition, 2 satellite lesions in the left lobe and sonographic evidence of invasion into the portal vein are present. Periportal lymph nodes are pathologically enlarged.

The physical examination is unremarkable, except for mild tenderness over the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Serum bilirubin, albumin, platelets, and international normalized ratio are normal, and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated at 1769 ng/mL. The patient’s family history is unremarkable for any major illness or cancer. Computed tomography scan of the chest and pelvis shows no evidence of other lesions. His liver disease is classified as Child–Pugh A. Due to locally advanced presentation, the tumor is deemed to be nontransplantable and unresectable, and is staged as BCLC-C. The patient continues to work and his performance status is ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) 0. He is referred to the liver tumor clinic for further evaluation and management. The tumor board consensus is to initiate systemic treatment.

What systemic treatment would you recommend for this patient with locally advanced unresectable HCC with nodal metastasis?

First-Line Therapeutic Options

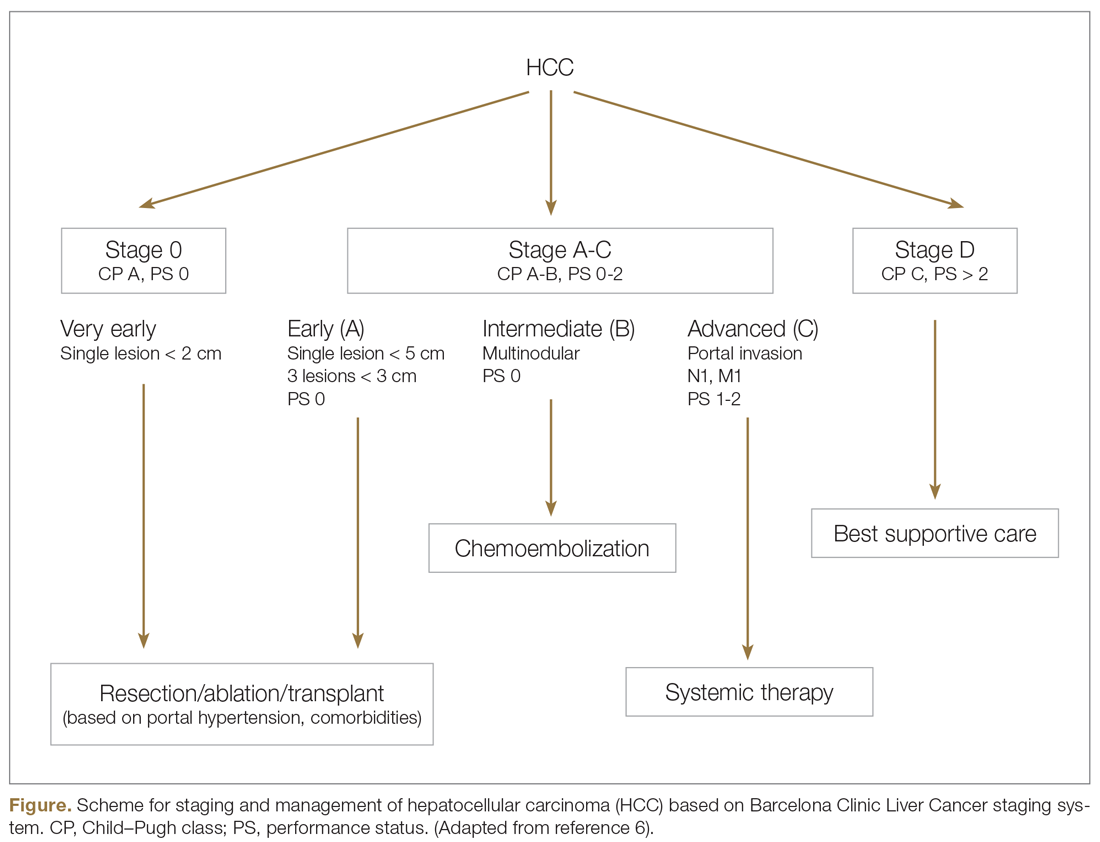

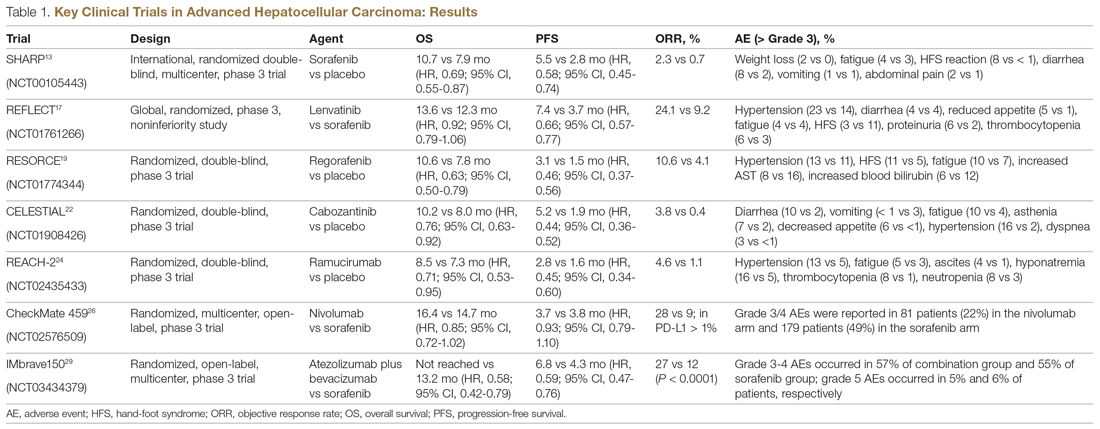

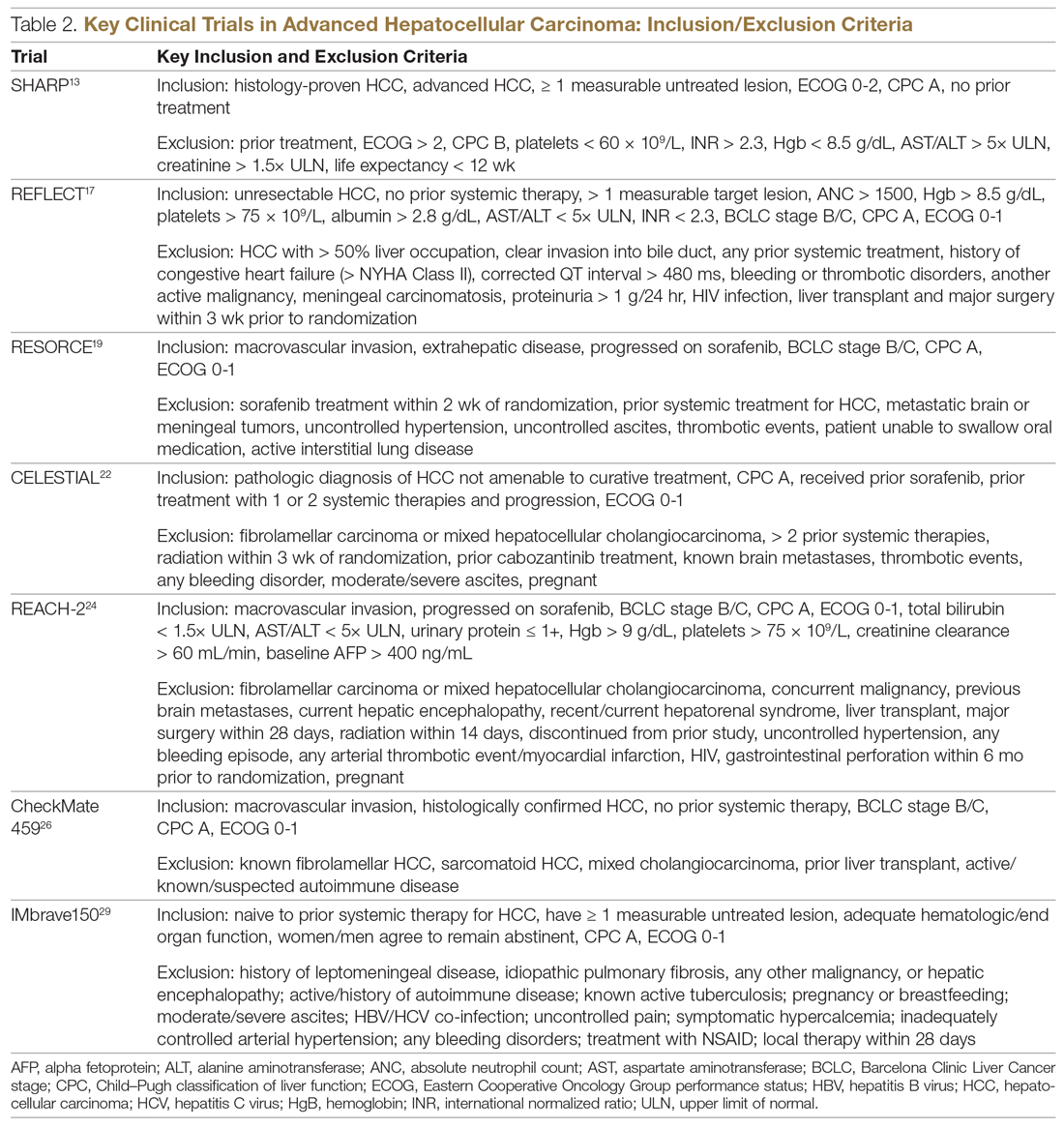

Systemic treatment of HCC is challenging because of the underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatic dysfunction present in most patients. Overall prognosis is therefore dependent on the disease biology and burden and on the degree of hepatic dysfunction. These factors must be considered in patients with advanced disease who present for systemic therapy. As such, patients with BCLC class D HCC with poor performance status and impaired liver function are better off with best supportive care and hospice services (Figure). Table 1 and Table 2 outline the landmark trials that led to the approval of agents for advanced HCC treatment.

Sorafenib

In the patient with BCLC class C HCC who has preserved liver function (traditionally based on a Child–Pugh score of ≤ 6 and a decent functional status [ECOG performance status 1-2]), sorafenib is the first FDA-approved first-line treatment. Sorafenib is a small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor that targets vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase signaling, in addition to many other tyrosine kinase pathways (including the platelet-derived growth factor and Raf-Ras pathways). Evidence for the clinical benefit of sorafenib comes from the SHARP trial.13 This was a multinational, but primarily European, randomized phase 3 study that compared sorafenib to best supportive care for advanced HCC in patients with a Child–Pugh score ≤ 6A and a robust performance status (ECOG 0 and 1). Overall survival (OS) with placebo and sorafenib was 7.9 months and 10.7 months, respectively. There was no difference in time to radiologic progression, and the progression-free survival (PFS) at 4 months was 62% with sorafenib and 42% with placebo. Patients with HCV-associated HCC appeared to derive a more substantial benefit from sorafenib.14 In a smaller randomized study of sorafenib in Asian patients with predominantly hepatitis B–associated HCC, OS in the sorafenib and best supportive care arms was lower than that reported in the SHARP study (6.5 months vs 4.2 months), although OS still was longer in the sorafenib group.15

Significant adverse events reported with sorafenib include fatigue (30%), hand and foot syndrome (30%), diarrhea (15%), and mucositis (10%). Major proportions of patients in the clinical setting have not tolerated the standard dose of 400 mg twice daily. Dose-adjusted administration of sorafenib has been advocated in patients with more impaired liver function (Child–Pugh class 7B) and bilirubin of 1.5 to 3 times the upper limit of normal, although it is unclear whether these patients are deriving any benefit from sorafenib.16 At this time, in a patient with preserved liver function, starting with 400 mg twice daily, followed by dose reduction based on toxicity, remains standard.

Lenvatinib

After multiple attempts to develop newer first-line treatments for HCC, lenvatinib, another small-molecule multikinase inhibitor of VEGFR signaling, was approved by the FDA in August 2018. Approval was based on a noninferiority study of lenvatinib versus sorafenib in patients with unresectable, treatment-naïve HCC who had preserved liver function and excellent performance status.17 Lenvatinib was noninferior to sorafenib, with an OS of 13.6 months versus 12.3 months for sorafenib. Lenvatinib was associated with an improved response rate (24% vs 9%), increased time to disease progression, and longer PFS (7.3 months vs 3.6 months). Patients with a performance status of 0 and 1 were allowed in this trial. Lenvatinib is associated with a more favorable adverse effect profile and is desirable in patients in whom tumor shrinkage is important. Compared to those treated with sorafenib, patients treated with lenvatinib reported a somewhat higher incidence of higher-grade hypertension (42% vs 30%), loss of appetite (34% vs 27%), and weight loss (31%), but lower rates of diarrhea (39% vs 46%) and skin toxicity (27% vs 52%).