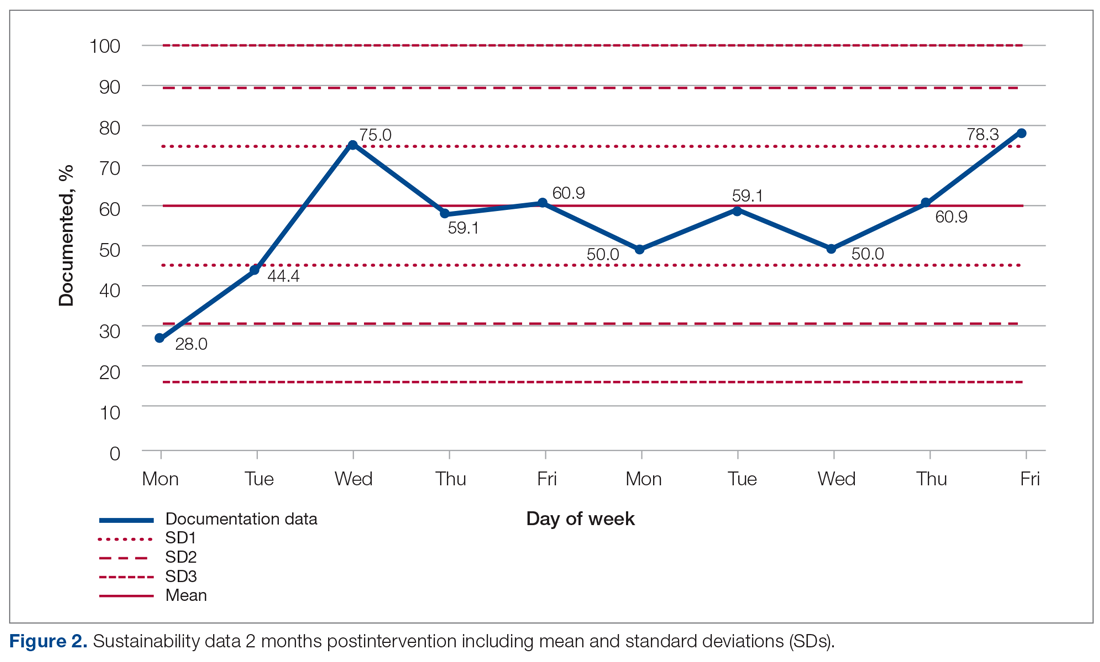

Figure 2 shows the sustainability of the intervention, which averaged 56.56% postintervention nearly 2 months later. The data returned to preintervention variability levels.

Discussion

Our project explored an important issue that was frequently encountered by department clinicians. Our team of FY2 doctors, in general, had little experience with quality improvement. We have developed our understanding and experience through planning, making, and measuring improvement.

It was challenging deciding on how to deal with the problem. A number of ways were considered to improve the paper rounding chart, but the nursing team had already planned to make changes to it. Bowel activity is mainly documented by nursing staff, but there was no specific protocol for recognizing constipation and when to inform the medical team. We decided to focus on doctors’ documentation in patient notes during the ward round, as this is where the decision regarding management of bowels is made, including interventions that could only be done by doctors, such as prescribing laxatives.

Strom et al9 have described a number of successful quality improvement interventions, and we decided to follow the authors’ guidance to implement a reminder system strategy using both posters and stickers to prompt doctors to document bowel activity. Both of these were simple, and the text on the poster was concise. The only cost incurred on the project was from printing the stickers; this totalled £2.99 (US $4.13). Individual stickers for each ward round entry were considered but not used, as it would create an additional task for doctors.

The data initially indicated that the interventions had their desired effect. However, this positive change was unsustainable, most likely suggesting that the novelty of the stickers and posters wore off at some point, leading to junior doctors no longer noticing them. Further Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles should examine the reasons why the change is difficult to sustain and implement new policies that aim to overcome them.