User login

Research and Reviews for the Practicing Oncologist

Trastuzumab-dkst approval adds to the biosimilar cancer drug market

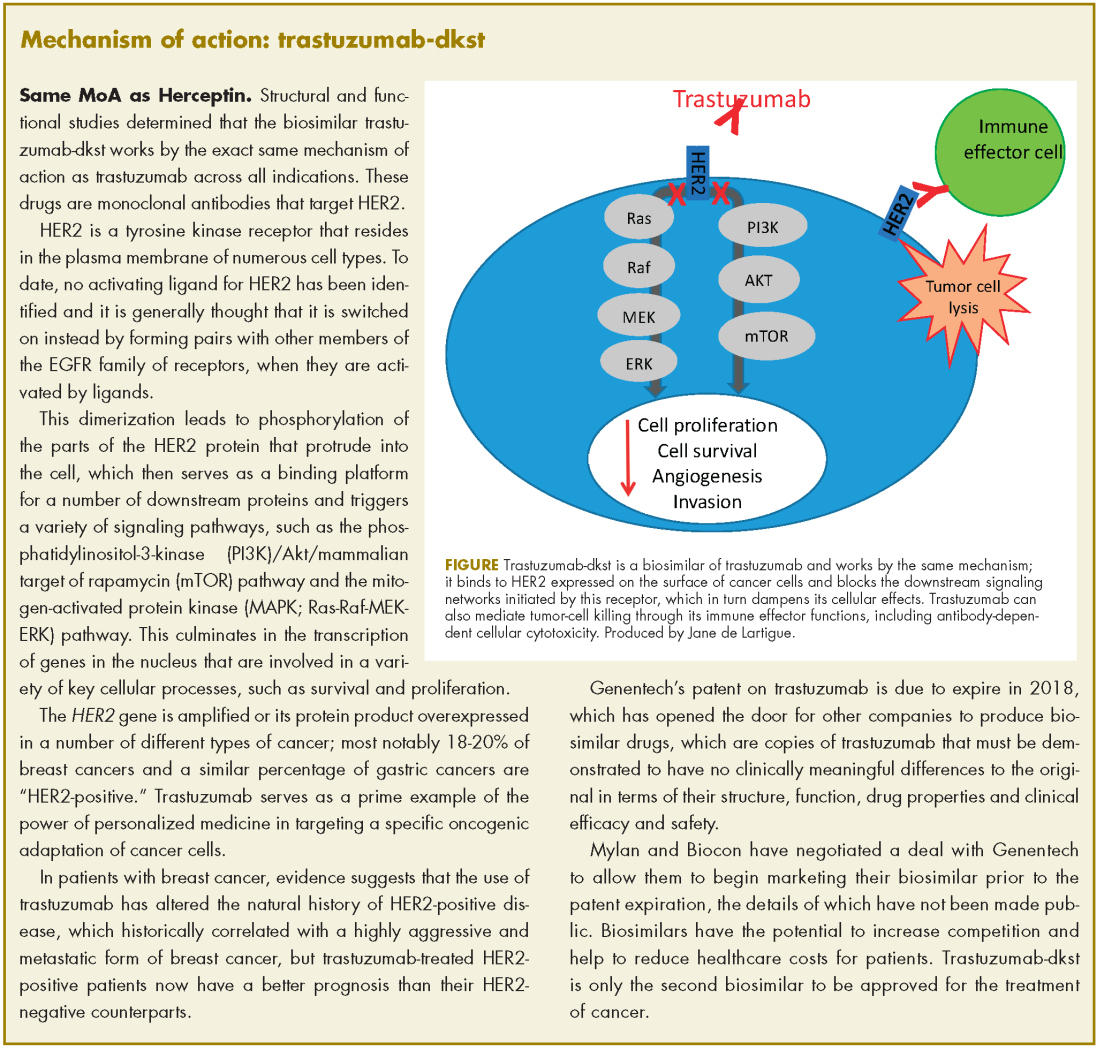

The human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-targeting monoclonal antibody trastuzumab-dkst, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive breast or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma.1 Trastuzumab-dkst, marketed as Ogviri by Mylan NV and Biocon Ltd, is a copy, known as a biosimilar, of Genentech’s trastuzumab (Herceptin), which has been approved in the US since 1998. Genentech’s patent on trastuzumab expires in 2018

Approval was based on a comparison of the 2 drugs, which demonstrated that there were no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product (trastuzumab) in terms of structure and function, pharmacokinetics (PKs), pharmacodynamics, and clinical efficacy and safety.

In structural and functional studies, trastuzumab-dkst was shown to have an identical amino acid sequence and a highly similar 3-dimensional structure, as well as equivalency in an inhibition of proliferation assay, a HER2-binding assay, and an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity assay, compared with trastuzumab.

Two nonclinical animal studies were performed in cynomolgus monkeys; a single-dose comparative PK study and a 4-week, repeat-dose toxicity study. That was further supported by data from a single-dose, randomized, double-blind, comparative 3-way PK study (MYL-HER-1002) in which 120 healthy men were given an 8 mg/kg infusion of trastuzumab-dkst, US-approved trastuzumab, or European Union (EU)-approved trastuzumab.

The key clinical study was the phase 3 HERiTAge trial, a 2-part, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel group trial that was performed in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had not been previously treated with either chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting.2

Eligible patients included males or females with measurably HER2-positive disease (as defined by HER2 overexpression determined by immunohistochemistry performed by a central laboratory), no exposure to chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 2, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) within institutional range of normal, and who had completed adjuvant trastuzumab therapy at least 1 year before.

Patients with central nervous system metastases had to have stable disease after treatment, and hormonal agents were required to be discontinued before the start of the study. Patients with a history of unstable angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction less than 1 year from randomization, other clinically significant cardiac disease, grade 2 or higher peripheral neuropathy, a history of any other cancer within 4 years before screening, or any significant medical illness that increased treatment risk or impeded evaluation, were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive trastuzumab-dkst or trastuzumab, both in combination with paclitaxel or docetaxel, at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg, followed by a maintenance dose of 6 mg/kg, every 3 weeks for a minimum of 7 cycles in part 1 of the study. Patients who had stable disease or better were enrolled in part 2 and continued treatment until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR) and, after 24 weeks, the ORR was 69.6% in the trastuzumab-dkst arm, compared with 64% in the trastuzumab arm, with a ratio of ORR of 1.09. Progression-free survival was also nearly identical in the 2 groups and median overall survival had not been reached in either arm.

The safety of the biosimilar and reference product were also highly similar. Serious adverse events occurred in 39.3%, compared with 37% of patients, respectively, with neutropenia the most frequently reported in both arms. Overall, treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 96.8%, compared with 94.7% of patients, respectively, with the majority of events mild or moderate in severity in both groups. This study also confirmed the low immunogenicity of the 2 drug products.

The prescribing information details the recommended doses of trastuzumab-dkst for each approved indication and warnings and precautions for cardiomyopathy, infusion reactions, pulmonary toxicity, exacerbation of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and embryofetal toxicity.3

Patients should undergo thorough cardiac assessments, including baseline LVEF measurement immediately before starting therapy, every 3 months during therapy, and upon completion of therapy. Patients who complete adjuvant therapy should have cardiac assessments every 6 months for at least 2 years. Treatment should be withheld for ≥16% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values or an LVEF value below institutional limits of normal and ≥10% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values. When treatment is withheld for significant LVEF cardiac dysfunction, patients should undergo cardiac assessment at 4-week intervals.

To combat infusion reactions, infusion should be interrupted in all patients experiencing dyspnea or clinically significant hypotension and medical therapy administered. Patients should be evaluated and monitored carefully until signs and symptoms resolve and permanent discontinuation considered in patients with severe reactions. Patients should be warned of the potential for fetal harm with trastuzumab-dkst and of the need for effective contraceptive use during and for 6 months after treatment

1. FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of certain breast and stomach cancers. FDA News Release. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm587378.htm. December 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

2. Rugo HS, Barve A, Waller CF, et al. Effect of a proposed trastuzumab biosimilar compared with trastuzumab on overall response rate in patients with ERBB2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):37-47.

3. Ogviri (trastuzumab-dkst) injection, for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Mylan, GMBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761074s000lbl.pdf. December, 2017. Accessed July 31, 2015.

The human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-targeting monoclonal antibody trastuzumab-dkst, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive breast or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma.1 Trastuzumab-dkst, marketed as Ogviri by Mylan NV and Biocon Ltd, is a copy, known as a biosimilar, of Genentech’s trastuzumab (Herceptin), which has been approved in the US since 1998. Genentech’s patent on trastuzumab expires in 2018

Approval was based on a comparison of the 2 drugs, which demonstrated that there were no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product (trastuzumab) in terms of structure and function, pharmacokinetics (PKs), pharmacodynamics, and clinical efficacy and safety.

In structural and functional studies, trastuzumab-dkst was shown to have an identical amino acid sequence and a highly similar 3-dimensional structure, as well as equivalency in an inhibition of proliferation assay, a HER2-binding assay, and an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity assay, compared with trastuzumab.

Two nonclinical animal studies were performed in cynomolgus monkeys; a single-dose comparative PK study and a 4-week, repeat-dose toxicity study. That was further supported by data from a single-dose, randomized, double-blind, comparative 3-way PK study (MYL-HER-1002) in which 120 healthy men were given an 8 mg/kg infusion of trastuzumab-dkst, US-approved trastuzumab, or European Union (EU)-approved trastuzumab.

The key clinical study was the phase 3 HERiTAge trial, a 2-part, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel group trial that was performed in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had not been previously treated with either chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting.2

Eligible patients included males or females with measurably HER2-positive disease (as defined by HER2 overexpression determined by immunohistochemistry performed by a central laboratory), no exposure to chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 2, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) within institutional range of normal, and who had completed adjuvant trastuzumab therapy at least 1 year before.

Patients with central nervous system metastases had to have stable disease after treatment, and hormonal agents were required to be discontinued before the start of the study. Patients with a history of unstable angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction less than 1 year from randomization, other clinically significant cardiac disease, grade 2 or higher peripheral neuropathy, a history of any other cancer within 4 years before screening, or any significant medical illness that increased treatment risk or impeded evaluation, were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive trastuzumab-dkst or trastuzumab, both in combination with paclitaxel or docetaxel, at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg, followed by a maintenance dose of 6 mg/kg, every 3 weeks for a minimum of 7 cycles in part 1 of the study. Patients who had stable disease or better were enrolled in part 2 and continued treatment until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR) and, after 24 weeks, the ORR was 69.6% in the trastuzumab-dkst arm, compared with 64% in the trastuzumab arm, with a ratio of ORR of 1.09. Progression-free survival was also nearly identical in the 2 groups and median overall survival had not been reached in either arm.

The safety of the biosimilar and reference product were also highly similar. Serious adverse events occurred in 39.3%, compared with 37% of patients, respectively, with neutropenia the most frequently reported in both arms. Overall, treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 96.8%, compared with 94.7% of patients, respectively, with the majority of events mild or moderate in severity in both groups. This study also confirmed the low immunogenicity of the 2 drug products.

The prescribing information details the recommended doses of trastuzumab-dkst for each approved indication and warnings and precautions for cardiomyopathy, infusion reactions, pulmonary toxicity, exacerbation of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and embryofetal toxicity.3

Patients should undergo thorough cardiac assessments, including baseline LVEF measurement immediately before starting therapy, every 3 months during therapy, and upon completion of therapy. Patients who complete adjuvant therapy should have cardiac assessments every 6 months for at least 2 years. Treatment should be withheld for ≥16% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values or an LVEF value below institutional limits of normal and ≥10% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values. When treatment is withheld for significant LVEF cardiac dysfunction, patients should undergo cardiac assessment at 4-week intervals.

To combat infusion reactions, infusion should be interrupted in all patients experiencing dyspnea or clinically significant hypotension and medical therapy administered. Patients should be evaluated and monitored carefully until signs and symptoms resolve and permanent discontinuation considered in patients with severe reactions. Patients should be warned of the potential for fetal harm with trastuzumab-dkst and of the need for effective contraceptive use during and for 6 months after treatment

The human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-targeting monoclonal antibody trastuzumab-dkst, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017 for the treatment of patients with HER2-positive breast or metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma.1 Trastuzumab-dkst, marketed as Ogviri by Mylan NV and Biocon Ltd, is a copy, known as a biosimilar, of Genentech’s trastuzumab (Herceptin), which has been approved in the US since 1998. Genentech’s patent on trastuzumab expires in 2018

Approval was based on a comparison of the 2 drugs, which demonstrated that there were no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar and the reference product (trastuzumab) in terms of structure and function, pharmacokinetics (PKs), pharmacodynamics, and clinical efficacy and safety.

In structural and functional studies, trastuzumab-dkst was shown to have an identical amino acid sequence and a highly similar 3-dimensional structure, as well as equivalency in an inhibition of proliferation assay, a HER2-binding assay, and an antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity assay, compared with trastuzumab.

Two nonclinical animal studies were performed in cynomolgus monkeys; a single-dose comparative PK study and a 4-week, repeat-dose toxicity study. That was further supported by data from a single-dose, randomized, double-blind, comparative 3-way PK study (MYL-HER-1002) in which 120 healthy men were given an 8 mg/kg infusion of trastuzumab-dkst, US-approved trastuzumab, or European Union (EU)-approved trastuzumab.

The key clinical study was the phase 3 HERiTAge trial, a 2-part, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel group trial that was performed in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had not been previously treated with either chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting.2

Eligible patients included males or females with measurably HER2-positive disease (as defined by HER2 overexpression determined by immunohistochemistry performed by a central laboratory), no exposure to chemotherapy or trastuzumab in the metastatic setting, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status of 0 or 2, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) within institutional range of normal, and who had completed adjuvant trastuzumab therapy at least 1 year before.

Patients with central nervous system metastases had to have stable disease after treatment, and hormonal agents were required to be discontinued before the start of the study. Patients with a history of unstable angina, heart failure, myocardial infarction less than 1 year from randomization, other clinically significant cardiac disease, grade 2 or higher peripheral neuropathy, a history of any other cancer within 4 years before screening, or any significant medical illness that increased treatment risk or impeded evaluation, were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive trastuzumab-dkst or trastuzumab, both in combination with paclitaxel or docetaxel, at a loading dose of 8 mg/kg, followed by a maintenance dose of 6 mg/kg, every 3 weeks for a minimum of 7 cycles in part 1 of the study. Patients who had stable disease or better were enrolled in part 2 and continued treatment until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR) and, after 24 weeks, the ORR was 69.6% in the trastuzumab-dkst arm, compared with 64% in the trastuzumab arm, with a ratio of ORR of 1.09. Progression-free survival was also nearly identical in the 2 groups and median overall survival had not been reached in either arm.

The safety of the biosimilar and reference product were also highly similar. Serious adverse events occurred in 39.3%, compared with 37% of patients, respectively, with neutropenia the most frequently reported in both arms. Overall, treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 96.8%, compared with 94.7% of patients, respectively, with the majority of events mild or moderate in severity in both groups. This study also confirmed the low immunogenicity of the 2 drug products.

The prescribing information details the recommended doses of trastuzumab-dkst for each approved indication and warnings and precautions for cardiomyopathy, infusion reactions, pulmonary toxicity, exacerbation of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and embryofetal toxicity.3

Patients should undergo thorough cardiac assessments, including baseline LVEF measurement immediately before starting therapy, every 3 months during therapy, and upon completion of therapy. Patients who complete adjuvant therapy should have cardiac assessments every 6 months for at least 2 years. Treatment should be withheld for ≥16% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values or an LVEF value below institutional limits of normal and ≥10% absolute decrease in LVEF from pre-treatment values. When treatment is withheld for significant LVEF cardiac dysfunction, patients should undergo cardiac assessment at 4-week intervals.

To combat infusion reactions, infusion should be interrupted in all patients experiencing dyspnea or clinically significant hypotension and medical therapy administered. Patients should be evaluated and monitored carefully until signs and symptoms resolve and permanent discontinuation considered in patients with severe reactions. Patients should be warned of the potential for fetal harm with trastuzumab-dkst and of the need for effective contraceptive use during and for 6 months after treatment

1. FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of certain breast and stomach cancers. FDA News Release. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm587378.htm. December 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

2. Rugo HS, Barve A, Waller CF, et al. Effect of a proposed trastuzumab biosimilar compared with trastuzumab on overall response rate in patients with ERBB2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):37-47.

3. Ogviri (trastuzumab-dkst) injection, for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Mylan, GMBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761074s000lbl.pdf. December, 2017. Accessed July 31, 2015.

1. FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of certain breast and stomach cancers. FDA News Release. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm587378.htm. December 1, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2018.

2. Rugo HS, Barve A, Waller CF, et al. Effect of a proposed trastuzumab biosimilar compared with trastuzumab on overall response rate in patients with ERBB2 (HER2)-positive metastatic breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(1):37-47.

3. Ogviri (trastuzumab-dkst) injection, for intravenous use. Prescribing information. Mylan, GMBH. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761074s000lbl.pdf. December, 2017. Accessed July 31, 2015.

Biosimilars: same ol’ – but with a suffix, and cheaper

Biosimilars have arrived, and chances are that you’re already prescribing them. Last September, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first cancer-specific biosimilar, bevacizumab-awwb, for multiple cancer types (p. e60);1 and in November, it approved trastuzumab-dkst for HER2-positive breast and gastrointestinal cancers (p. e63).1 Briefly, biosimilars are biologic products that show comparable quality, efficacy, and safety to an existing, approved biologic known as the reference product.

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin are easy to replicate identically, whereas biosimilars are large, complex proteins that are manufactured in nature’s factory, a micro-organism or biologic cell.2 The manufacturing process must be nearly identical to that for the reference product, so that only insignificant/nonclinically significant impurities occur in the final product. The protein-amino acid sequence is key and must therefore be identical. The 2010 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act established an abbreviated pathway for the FDA to consider and approve biosimilars, and 5 years later, the bone marrow stimulant filgrastim-sndz became the first biosimilar approved for use in the United States.3 The development of biosimilars is not inexpensive. The law and the FDA approval system require preclinical and phase 1 testing, and a robust phase 3 trial against the reference product to demonstrate that safety and efficacy are statistically not different and that any chemical differences between the biosimilar and reference product are clinically and safety or immunogenically insignificant. When those criteria have been met, and the biosimilar approved, the clinical and cost benefits to patients could be significant. In general, the cost of a biosimilar is about 20% to 30% lower than that of the reference product.

Biosimilarity does not yet allow interchangeability. Small-molecule generics under FDA regulations are interchangeable in the drug store and the hospital without the prescriber or patient being aware. That is not yet the case with biosimilars, but their lower prices could have a notable impact on overall cost of care. In 2013, 7 of the top 8 best-selling drugs in the global market were biologics.4 Three of the top 8 – rituximab, trastuzumab, and bevacizumab – were used to treat cancer, and 1 (pegfilgrastim) was for therapy-related neutropenia. Their total cost was US$27 billion. Biosimilars of those therapies could significantly lower that amount.

Nabhan and colleagues interviewed 510 US-based community oncologists about their understanding of biosimilars. They found that only 29% of respondents said they prescribed filgrastim-sndz for supportive care by personal choice, but upward of 73% said they would prescribe biosimilars for the active anticancer therapies, trastuzumab and bevacizumab. There’s no question that biosimilars are here to stay. The requirements to make them have been well worked out. Their safety and efficacy therefore can be assured, and their lower prices promise cost savings for patients and society as a whole.

1. Bosserman L. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. https://www. mdedge.com/jcso/article/154559/cancer-care-2017-promise-morecures- challenges-unstable-health-care-system. December 15, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Biosimilar and interchangeable products. FDA website. https://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsare DevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/Therapeutic BiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm#biological. Last updated October 23, 2017. Accessed April 25, 2018.

3. de Lartigue J. Filgrastim-sndz debuts as the first biosimilar approved in United States. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/105177/patientsurvivor- care/filgrastim-sndz-debuts-first-biosimilar-approved-united. Published December 2015. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4 . The Dish. Biologics still on top in best selling drugs of 2013. http:// cellculturedish.com/2014/03/top-ten-biologics-2013-us-pharmaceutical- sales-2/. March 13, 2014. Accessed April 26, 2018.

5. Nabhan C, Jeune-Smith Y, Valley A, Feinberg BA. Community Oncologists’ Perception and Acceptance of Biosimilars in Oncology. https://www.journalofclinicalpathways.com/article/communityoncologists- perception-and-acceptance-biosimilars-oncology. Published March 2018. Accessed April 24, 2018.

Biosimilars have arrived, and chances are that you’re already prescribing them. Last September, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first cancer-specific biosimilar, bevacizumab-awwb, for multiple cancer types (p. e60);1 and in November, it approved trastuzumab-dkst for HER2-positive breast and gastrointestinal cancers (p. e63).1 Briefly, biosimilars are biologic products that show comparable quality, efficacy, and safety to an existing, approved biologic known as the reference product.

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin are easy to replicate identically, whereas biosimilars are large, complex proteins that are manufactured in nature’s factory, a micro-organism or biologic cell.2 The manufacturing process must be nearly identical to that for the reference product, so that only insignificant/nonclinically significant impurities occur in the final product. The protein-amino acid sequence is key and must therefore be identical. The 2010 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act established an abbreviated pathway for the FDA to consider and approve biosimilars, and 5 years later, the bone marrow stimulant filgrastim-sndz became the first biosimilar approved for use in the United States.3 The development of biosimilars is not inexpensive. The law and the FDA approval system require preclinical and phase 1 testing, and a robust phase 3 trial against the reference product to demonstrate that safety and efficacy are statistically not different and that any chemical differences between the biosimilar and reference product are clinically and safety or immunogenically insignificant. When those criteria have been met, and the biosimilar approved, the clinical and cost benefits to patients could be significant. In general, the cost of a biosimilar is about 20% to 30% lower than that of the reference product.

Biosimilarity does not yet allow interchangeability. Small-molecule generics under FDA regulations are interchangeable in the drug store and the hospital without the prescriber or patient being aware. That is not yet the case with biosimilars, but their lower prices could have a notable impact on overall cost of care. In 2013, 7 of the top 8 best-selling drugs in the global market were biologics.4 Three of the top 8 – rituximab, trastuzumab, and bevacizumab – were used to treat cancer, and 1 (pegfilgrastim) was for therapy-related neutropenia. Their total cost was US$27 billion. Biosimilars of those therapies could significantly lower that amount.

Nabhan and colleagues interviewed 510 US-based community oncologists about their understanding of biosimilars. They found that only 29% of respondents said they prescribed filgrastim-sndz for supportive care by personal choice, but upward of 73% said they would prescribe biosimilars for the active anticancer therapies, trastuzumab and bevacizumab. There’s no question that biosimilars are here to stay. The requirements to make them have been well worked out. Their safety and efficacy therefore can be assured, and their lower prices promise cost savings for patients and society as a whole.

Biosimilars have arrived, and chances are that you’re already prescribing them. Last September, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first cancer-specific biosimilar, bevacizumab-awwb, for multiple cancer types (p. e60);1 and in November, it approved trastuzumab-dkst for HER2-positive breast and gastrointestinal cancers (p. e63).1 Briefly, biosimilars are biologic products that show comparable quality, efficacy, and safety to an existing, approved biologic known as the reference product.

Small-molecule drugs such as aspirin are easy to replicate identically, whereas biosimilars are large, complex proteins that are manufactured in nature’s factory, a micro-organism or biologic cell.2 The manufacturing process must be nearly identical to that for the reference product, so that only insignificant/nonclinically significant impurities occur in the final product. The protein-amino acid sequence is key and must therefore be identical. The 2010 Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act established an abbreviated pathway for the FDA to consider and approve biosimilars, and 5 years later, the bone marrow stimulant filgrastim-sndz became the first biosimilar approved for use in the United States.3 The development of biosimilars is not inexpensive. The law and the FDA approval system require preclinical and phase 1 testing, and a robust phase 3 trial against the reference product to demonstrate that safety and efficacy are statistically not different and that any chemical differences between the biosimilar and reference product are clinically and safety or immunogenically insignificant. When those criteria have been met, and the biosimilar approved, the clinical and cost benefits to patients could be significant. In general, the cost of a biosimilar is about 20% to 30% lower than that of the reference product.

Biosimilarity does not yet allow interchangeability. Small-molecule generics under FDA regulations are interchangeable in the drug store and the hospital without the prescriber or patient being aware. That is not yet the case with biosimilars, but their lower prices could have a notable impact on overall cost of care. In 2013, 7 of the top 8 best-selling drugs in the global market were biologics.4 Three of the top 8 – rituximab, trastuzumab, and bevacizumab – were used to treat cancer, and 1 (pegfilgrastim) was for therapy-related neutropenia. Their total cost was US$27 billion. Biosimilars of those therapies could significantly lower that amount.

Nabhan and colleagues interviewed 510 US-based community oncologists about their understanding of biosimilars. They found that only 29% of respondents said they prescribed filgrastim-sndz for supportive care by personal choice, but upward of 73% said they would prescribe biosimilars for the active anticancer therapies, trastuzumab and bevacizumab. There’s no question that biosimilars are here to stay. The requirements to make them have been well worked out. Their safety and efficacy therefore can be assured, and their lower prices promise cost savings for patients and society as a whole.

1. Bosserman L. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. https://www. mdedge.com/jcso/article/154559/cancer-care-2017-promise-morecures- challenges-unstable-health-care-system. December 15, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Biosimilar and interchangeable products. FDA website. https://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsare DevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/Therapeutic BiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm#biological. Last updated October 23, 2017. Accessed April 25, 2018.

3. de Lartigue J. Filgrastim-sndz debuts as the first biosimilar approved in United States. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/105177/patientsurvivor- care/filgrastim-sndz-debuts-first-biosimilar-approved-united. Published December 2015. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4 . The Dish. Biologics still on top in best selling drugs of 2013. http:// cellculturedish.com/2014/03/top-ten-biologics-2013-us-pharmaceutical- sales-2/. March 13, 2014. Accessed April 26, 2018.

5. Nabhan C, Jeune-Smith Y, Valley A, Feinberg BA. Community Oncologists’ Perception and Acceptance of Biosimilars in Oncology. https://www.journalofclinicalpathways.com/article/communityoncologists- perception-and-acceptance-biosimilars-oncology. Published March 2018. Accessed April 24, 2018.

1. Bosserman L. Cancer care in 2017: the promise of more cures with the challenges of an unstable health care system. https://www. mdedge.com/jcso/article/154559/cancer-care-2017-promise-morecures- challenges-unstable-health-care-system. December 15, 2017. Accessed April 23, 2018.

2. Biosimilar and interchangeable products. FDA website. https://www. fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsare DevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/Therapeutic BiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm580419.htm#biological. Last updated October 23, 2017. Accessed April 25, 2018.

3. de Lartigue J. Filgrastim-sndz debuts as the first biosimilar approved in United States. https://www.mdedge.com/jcso/article/105177/patientsurvivor- care/filgrastim-sndz-debuts-first-biosimilar-approved-united. Published December 2015. Accessed April 23, 2018.

4 . The Dish. Biologics still on top in best selling drugs of 2013. http:// cellculturedish.com/2014/03/top-ten-biologics-2013-us-pharmaceutical- sales-2/. March 13, 2014. Accessed April 26, 2018.

5. Nabhan C, Jeune-Smith Y, Valley A, Feinberg BA. Community Oncologists’ Perception and Acceptance of Biosimilars in Oncology. https://www.journalofclinicalpathways.com/article/communityoncologists- perception-and-acceptance-biosimilars-oncology. Published March 2018. Accessed April 24, 2018.

Isolated ocular metastases from lung cancer

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

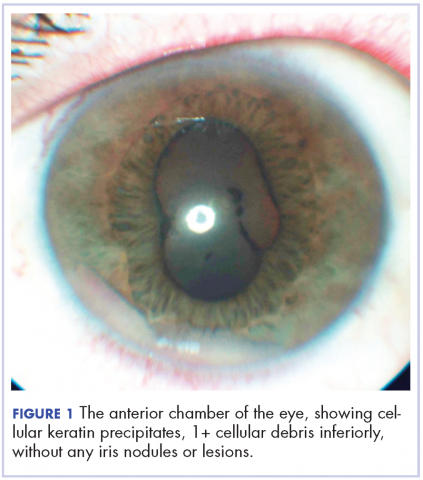

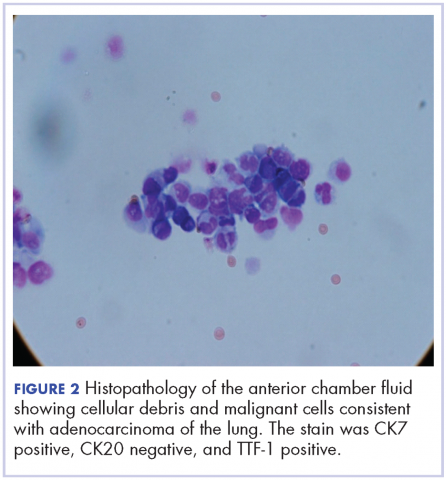

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

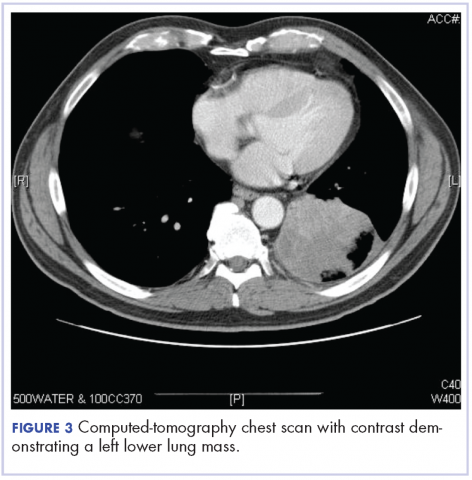

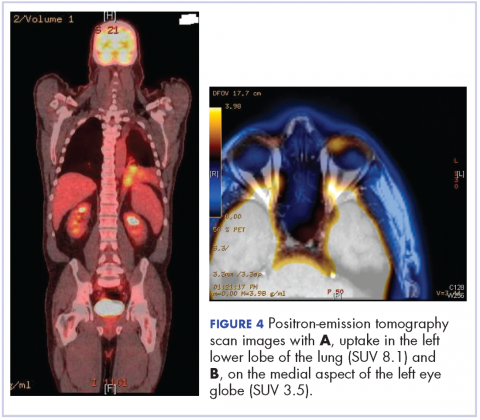

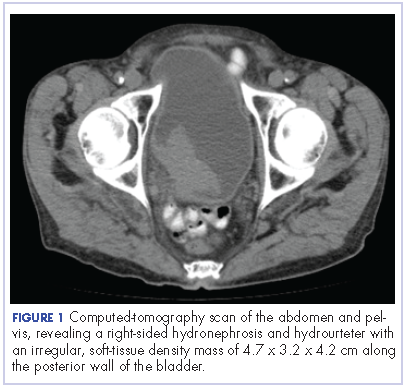

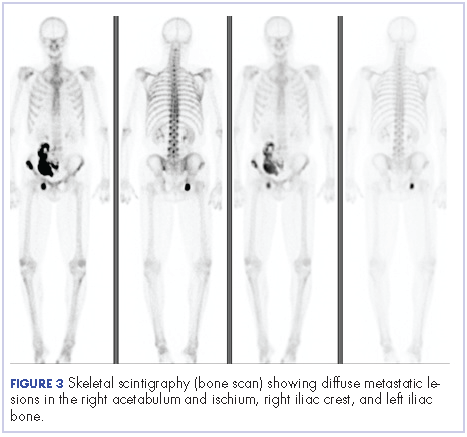

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

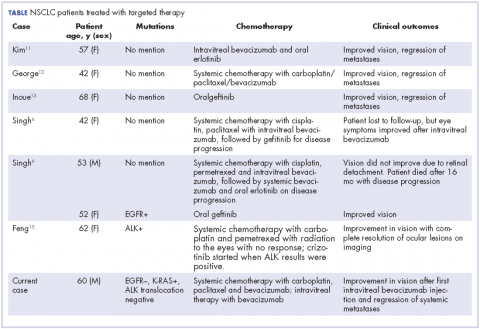

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

Non–small cell lung cancer constitutes 80%-85% of lung cancers, and 40% of NSCLC are adenocarcinoma. It is rare to find intraocular metastasis from lung cancer. In this article, we present the case of a patient who presented with complaints of diminished vision redness of the eye and was found to have intra-ocular metastases from lung cancer.

Case presentation and summary

A 60-year-old man with a 40-pack per year history of smoking presented to multiple ophthalmologists with complaints of decreased vision and redness of the left eye. He was eventually evaluated by an ophthalmologist who performed a biopsy of the anterior chamber of the eye. Histologic findings were consistent with adenocarcinoma of lung primary (Figures 1 and 2).

After the diagnosis, a chest X-ray showed that the patient had a left lower lung mass. The results of his physical exam were all within normal limits, with the exception of decreased visual acuity in the left eye. The results of his laboratory studies, including complete blood count and serum chemistries, were also within normal limits. Imaging studies – including a computed-tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis and a full-body positron-emission tomography–CT scan – showed a hypermetabolic left lower lobe mass 4.5 cm and right lower paratracheal lymph node metastasis 2 cm with a small focus of increased uptake alone the medial aspect of the left globe (Figures 3 and 4).

An MRI orbit was performed in an attempt to better characterize the left eye mass, but no optic lesion was identified. A biopsy of the left lower lung mass was consistent with non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Aside from the isolated left eye metastases, the patient did not have evidence of other distant metastatic involvement.

He was started on palliative chemotherapy on a clinical trial and received intravenous carboplatin AUC 6, pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks. He received 1 dose intraocular bevacizumab injection before initiation of systemic chemotherapy as he was symptomatic from the intraocular metastases. Within 2 weeks after intravitreal bevacizumab was administered, the patient had subjective improvement in vision. Mutational analysis to identify if the patient would benefit from targeted therapy showed no presence of EGFR mutation and ALK gene rearrangement, and that the patient was K-RAS mutant.

After treatment initiation, interval imaging studies (a computed-tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, pelvis; and magnetic-resonance imaging of the brain) after 3 cycles showed no evidence of disease progression, and after 4 cycles of chemotherapy with these drugs, the patient was started on maintenance chemotherapy with bevacizumab 15 mg/kg and pemetrexed 500 mg/m2.

Discussion

Choroidal metastasis is the most common site of intraocular tumor. In an autopsy study of 230 patients with carcinoma, 12% of cases demonstrated histologic evidence of ocular metastasis.1 A retrospective series of patients with malignant involvement of the eye, 66% of patients had a known history of primary cancer and in 34% of patients the ocular tumor was the first sign of cancer.2 The most common cancers that were found to have ocular metastasis were lung and breast cancer.2 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histologic type of lung cancer to result in ocular metastases and was seen in 41% of patients.3

Decreased or blurred vision with redness as the primary complaint of NSCLC is rare. Only a few case reports are available. Abundo and colleagues reported that 0.7%-12% of patients with lung cancer develop ocular metastases.4 Therefore, routine ophthalmologic screening for ocular metastases in patients with cancer has not been pursued in asymptomatic patients.5 Ophthalmological evaluation is recommended in symptomatic patients.

Metastatic involvement of two or more other organs was found to be a risk factor for development of choroidal metastasis in patients with lung cancer though in our patient no evidence of other organ involvement was found.5 The most common site of metastases in patients with NSCLC with ocular metastases was found to be the liver. Choroidal metastases was reported to be the sixth common site of metastases in patients with lung cancer.5

Treatment of ocular manifestations has been generally confined to surgical resection or radiation therapy, but advances in chemotherapy and development of novel targeted agents have shown promising results.7 Median life expectancy after a diagnosis of uveal metastases was reported to be 12 months in a retrospective study, which is similar to the reported median survival in metastatic NSCLC.8

Our patient was enrolled in a clinical trial and was treated with a regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and bevacizumab. On presentation, he had significant impairment of vision with pain. He was treated with intravitreal bevacizumab yielding improvement in his visual symptoms. Bevacizumab is a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody approved for use in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Other pathways that have been reported in development of lung cancer involve the ALK gene translocation, and EGFR and K-RAS mutations, and targeted therapy has shown good results in cancer patients with these molecular defects. Randomized clinical trials in patients with advanced NSCLC and an EGFR mutation have shown significant improvement in overall survival with the use of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor.9 Similarly, crizotinib has shown promising results in patients with metastatic NSCLC who have ELM-ALK rearrangement.10 As our patient’s tumor did not have either of these mutations, he was initiated on chemotherapy with bevacizumab. The presence of a K-RAS mutation in this patient further supported the use of front-line chemotherapy given that it may confer resistance against agents that target the EGFR pathway.

In our review of the literature, we found cases of patients with ocular metastases who responded well to therapy with targeted agents (Table).

Singh and colleagues did a systematic review of 55 cases of patients with lung cancer and choroidal metastases and found that the type of therapy depended on when the diagnosis had been made in relation to the advent of targeted therapy: cases diagnosed before targeted therapy had received radiation therapy or enucleation.6 As far as we could ascertain, there have been no randomized studies evaluating the impact of various targeted therapies or systemic chemotherapy on ocular metastases, although case reports have documented improvement in vision and regression of metastases with such therapy.

Conclusion

The goal of therapy in metastatic lung cancer is palliation of symptoms and improvement in patient quality of life with prolongation in overall survival. The newer targeted chemotherapeutic agents assist in achieving these goals and may decrease the morbidity associated from radiation or surgery with improvement in vision and regression of ocular metastatic lesions. Targeted therapies should be considered in the treatment of patients with ocular metastases from NSCLC.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

1. Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol-Chic. 1971;85(6):673-675.

2. Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, Schwartz GP, Lally SE. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265-1276.

3. Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Wiegel T, Krause L, Foerster MH. Incidence and clinical characteristics of symptomatic choroidal metastasis from lung cancer. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(5):515-519.

4. Abundo RE, Orenic CJ, Anderson SF, Townsend JC. Choroidal metastases resulting from carcinoma of the lung. J Am Optom Assoc. 1997;68(2):95-108.

5. Kreusel KM, Wiegel T, Stange M, Bornfeld N, Hinkelbein W, Foerster MH. Choroidal metastasis in disseminated lung cancer: frequency and risk factors. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134(3):445-447.

6. Singh N, Kulkarni P, Aggarwal AN, et al. Choroidal metastasis as a presenting manifestation of lung cancer: a report of 3 cases and systematic review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91(4):179-194.

7. Chen CJ, McCoy AN, Brahmer J, Handa JT. Emerging treatments for choroidal metastases. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56(6):511-521.

8. Shah SU, Mashayekhi A, Shields CL, et al. Uveal metastasis from lung cancer: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in 194 patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):352-357.

9. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123-132.

10. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2385-2394.

11. Kim SW, Kim MJ, Huh K, Oh J. Complete regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to non-small-cell lung cancer with intravitreal bevacizumab and oral erlotinib combination therapy. Ophthalmologica. 2009;223(6):411-413.

12. George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, Choong NW. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661-662.

13. Inoue M, Watanabe Y, Yamane S, et al. Choroidal metastasis with adenocarcinoma of the lung treated with gefitinib. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2010;20(5):963-965.

14. Shimomura I, Tada Y, Miura G, et al. Choroidal metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer that responded to gefitinib. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/criopm/2013/213124/. Published 2013. Accessed May 4, 2017.

15. Feng Y, Singh AD, Lanigan C, Tubbs RR, Ma PC. Choroidal metastases responsive to crizotinib therapy in a lung adenocarcinoma patient with ALK 2p23 fusion identified by ALK immunohistochemistry. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(12):e109-111.

Resolution of refractory pruritus with aprepitant in a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

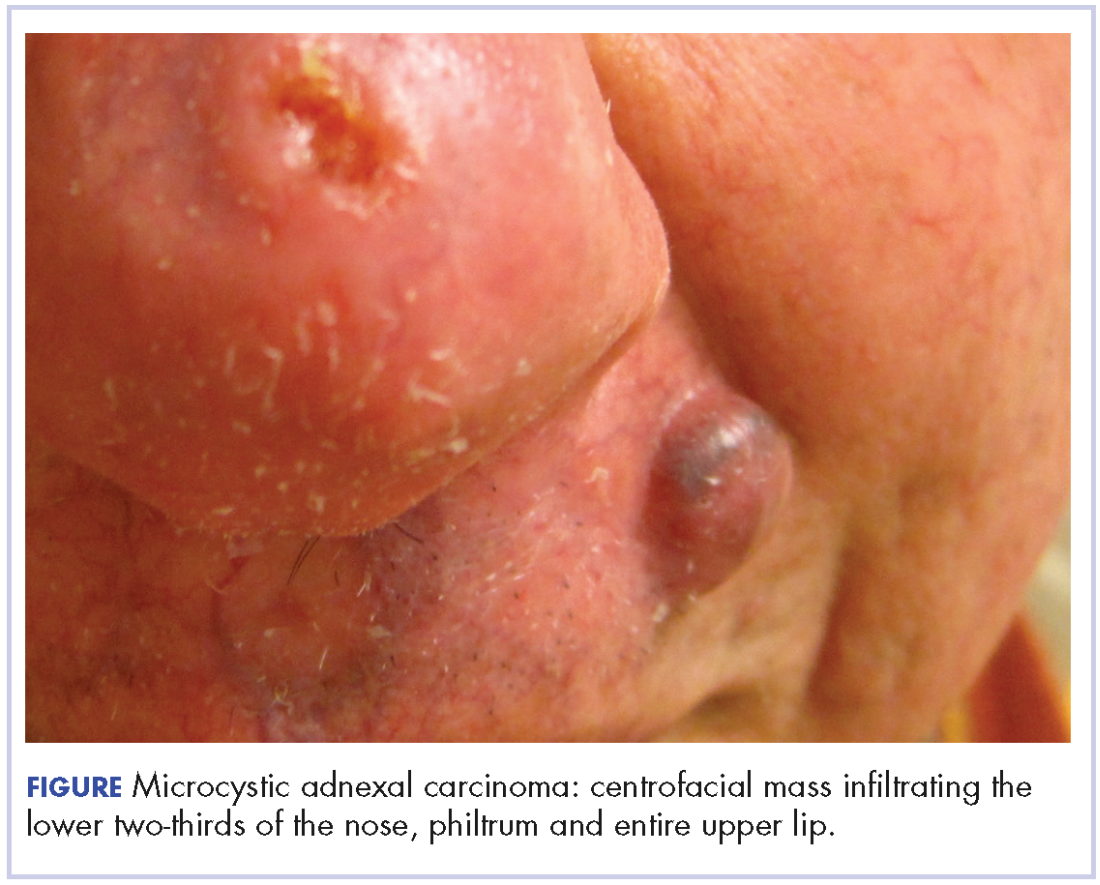

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4

The clinical presentation of MAC includes smooth, flesh-colored or yellow papules, nodules, or plaques.3 Patients often present with numbness, paresthesia, and burning in the area of involvement because of neural infiltration with tumor. Despite the rarity of MAC, pruritus has been reported as a presenting symptom in 1 other case in the literature.4 Our case represents the first report of MAC presenting with a grossly enlarging centrofacial mass, lymph node involvement, and severe full-body pruritus. Our patient responded completely, and within hours, to treatment with aprepitant after experiencing months of failure with conventional antipruritus treatments and without recurrence in symptoms in more than 2 years of follow-up.

Aprepitant blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor NK-1 and has been approved as an anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients. Substance P has been shown to be important in both nausea and itch pathways. The largest prospective study to date on aprepitant for the indication of pruritus in 45 patients with metastatic solid tumors demonstrated a 91% response rate, defined by >50% reduction in pruritus intensity, and 13% recurrence rate that occurred at a median of 7 weeks after initial treatment.5 Aprepitant treatment has been used with success for pruritus associated with both malignant and nonmalignant conditions in at least 74 patients,6 among whom the malignant conditions included cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.5-7 Aprepitant has also been used for erlotinib- and nivolumab-induced pruritus in non–small cell lung cancer, which suggests a possible future role for aprepitant in the treatment of pruritus secondary to novel cancer therapies, perhaps including immune checkpoint inhibitors.8-10

However, despite those reports, and likely owing to the multifactorial nature of pruritus, aprepitant is not unviversally effective. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated itch are yet to be elucidated, and optimal patient selection for aprepitant use needs to be determined. However, our patient’s notable response supports the increasing evidence that substance P is a key mediator of pruritus and that disruption of binding to its receptor may result in significant improvement in symptoms in certain patients. It remains to be seen whether the cell type or the tendency toward neural invasion plays a role. Large, randomized studies are needed to guide patient selection and confirm the findings reported here and in the literature, with careful documentation of and close attention paid to timing of pruritus relief and improvement in patient quality of life. Aprepitant might be an important therapeutic tool for refractory, malignancy-associated pruritus, in which patient quality of life is especially critical.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care and Cancer Meeting, in Miami Florida, June 26-28, 2014. The authors are indebted to Saajar Jadeja for his assistance preparing the manuscript.

1. Wallengren J. Neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of itch. Dermatol Ther. 2005;18(4):292-303.

2. Kulka M, Sheen CH, Tancowny BP, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP. Neuropeptides activate human mast cell degranulation and chemokine production. Immunology. 2008;123(3):398-410.

3. Wetter R, Goldstein GD. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(6):452-458.

4. Adamson T. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Dermatol Nurs. 2004;16(4):365.

5. Santini D, Vincenzi B, Guida FM, et al. Aprepitant for management of severe pruritus related to biological cancer treatments: a pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):1020-1024.

6. Song JS, Tawa M, Chau NG, Kupper TS, LeBoeuf NR. Aprepitant for refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-associated pruritus: 4 cases and a review of the literature. BMC Cancer. 2017;17.

7. Villafranca JJA, Siles MG, Casanova M, Goitia BT, Domínguez AR. Paraneoplastic pruritus presenting with Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2014;8:300.

8. Ito J, Fujimoto D, Nakamura A, et al. Aprepitant for refractory nivolumab-induced pruritus. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2017;109:58-61.

9. Levêque D. Aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1680-1681; author reply 1681.

10. Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Homey B. More on aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):486-487.

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4

The clinical presentation of MAC includes smooth, flesh-colored or yellow papules, nodules, or plaques.3 Patients often present with numbness, paresthesia, and burning in the area of involvement because of neural infiltration with tumor. Despite the rarity of MAC, pruritus has been reported as a presenting symptom in 1 other case in the literature.4 Our case represents the first report of MAC presenting with a grossly enlarging centrofacial mass, lymph node involvement, and severe full-body pruritus. Our patient responded completely, and within hours, to treatment with aprepitant after experiencing months of failure with conventional antipruritus treatments and without recurrence in symptoms in more than 2 years of follow-up.

Aprepitant blocks the binding of substance P to its receptor NK-1 and has been approved as an anti-emetic for chemotherapy patients. Substance P has been shown to be important in both nausea and itch pathways. The largest prospective study to date on aprepitant for the indication of pruritus in 45 patients with metastatic solid tumors demonstrated a 91% response rate, defined by >50% reduction in pruritus intensity, and 13% recurrence rate that occurred at a median of 7 weeks after initial treatment.5 Aprepitant treatment has been used with success for pruritus associated with both malignant and nonmalignant conditions in at least 74 patients,6 among whom the malignant conditions included cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, and metastatic solid tumors.5-7 Aprepitant has also been used for erlotinib- and nivolumab-induced pruritus in non–small cell lung cancer, which suggests a possible future role for aprepitant in the treatment of pruritus secondary to novel cancer therapies, perhaps including immune checkpoint inhibitors.8-10

However, despite those reports, and likely owing to the multifactorial nature of pruritus, aprepitant is not unviversally effective. Mechanisms of malignancy-associated itch are yet to be elucidated, and optimal patient selection for aprepitant use needs to be determined. However, our patient’s notable response supports the increasing evidence that substance P is a key mediator of pruritus and that disruption of binding to its receptor may result in significant improvement in symptoms in certain patients. It remains to be seen whether the cell type or the tendency toward neural invasion plays a role. Large, randomized studies are needed to guide patient selection and confirm the findings reported here and in the literature, with careful documentation of and close attention paid to timing of pruritus relief and improvement in patient quality of life. Aprepitant might be an important therapeutic tool for refractory, malignancy-associated pruritus, in which patient quality of life is especially critical.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care and Cancer Meeting, in Miami Florida, June 26-28, 2014. The authors are indebted to Saajar Jadeja for his assistance preparing the manuscript.

Substance P is an important neurotransmitter implicated in itch pathways.1 After binding to its receptor, neurokinin-1 (NK-1), substance P induces release of factors including histamine, which may cause pruritus.2 Recent literature has reported successful use of aprepitant, an NK-1 antagonist that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, for treatment of pruritus. We report here the case of a patient with microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC) who presented with refractory pruritus and who had rapid and complete resolution of itch after administration of aprepitant.

Case presentation and summary

A 73-year-old man presented with a 12-year history of a small nodule on his philtrum, which had been increasing in size. He subsequently developed upper-lip numbness and nasal induration. He complained of 2.5 months of severe, debilitating, full-body pruritus. His symptoms were refractory to treatment with prednisone, gabapentin, doxycycline, doxepin, antihistamines, and topical steroids. At the time of consultation, he was being treated with hydroxyzine and topical pramocaine lotion with minimal relief.

At initial dermatologic evaluation, his tumor involved the lower two-thirds of the nose and entire upper cutaneous lip. There was a 4-mm rolled ulcer on the nasal tip and a 1-cm exophytic, smooth nodule on the left upper lip with palpable 4-cm submandibular adenopathy (Figure). Skin examination otherwise revealed linear excoriations on the upper back with no additional primary lesions. The nodule was biopsied, and the patient was diagnosed with MAC with gross nodal involvement. Laboratory findings including serum chemistries, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood cell count, thyroid, and liver function were normal. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for distant metastases.

Treatment was initiated with oral aprepitant – 125 mg on day 1, 80 mg on day 2, and 80 mg on day 3 –with concomitant weekly carboplatin (AUC 1.5) and paclitaxel (30 mg/m2) as well as radiation. Within hours after the first dose of aprepitant, the patient reported a notable cessation in his pruritus. He reported that after 5 hours, his skin “finally turned off” and over the hour that followed, he had complete resolution of symptoms. He completed chemoradiation with a significant disease response. Despite persistent MAC confined to the philtrum, he has been followed for over 2 years without recurrence of itch.

Discussion

MAC is an uncommon cutaneous malignancy of sweat and eccrine gland differentiation. In all, 700 cases of MAC have been described in the literature; a 2008 review estimated the incidence of metastasis at around 2.1%.3 Though metastasis is exceedingly rare, the tumor is locally aggressive and there are reports of invasion into the muscle, perichondrium, periosteum, bone marrow, as well as perineural spaces and vascular adventitia.4