User login

American Epilepsy Society (AES): Annual Meeting

AES: Development of unobtrusive seizure-detection devices continues

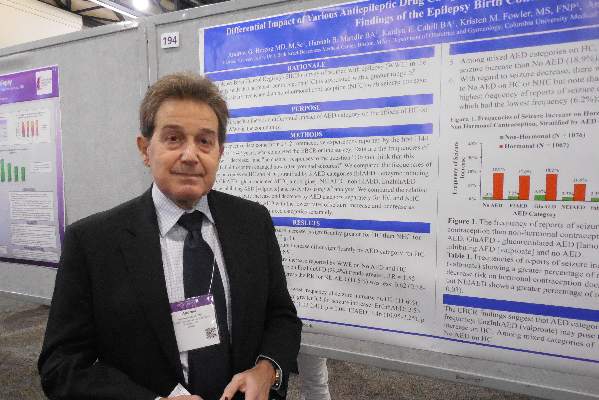

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Reliable, externally worn seizure-detection devices for epilepsy patients have been eagerly sought but elusive. New results from the pivotal trial of an arm-mounted device that works by analyzing skin electromyography showed promise when tested in 142 adults and children with epilepsy who also underwent video EEG monitoring, Dr. José E. Cavazos reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

More than 7,000 hours of simultaneous surface electromyography with the investigational device, worn on the patient’s upper arm, and video EEG monitoring as the gold standard for seizure detection showed that the device correctly identified all 29 generalized tonic-clonic seizures experienced by the 142 patients studied. This level of detection came with a false-positive rate of 1.47 false events during every 24 hours of monitoring, with most of the false positives occurring when the device was being placed or removed.

The results made Dr. Cavazos hopeful that the Food and Drug Administration would clear the device, the Brain Sentinel Seizure Detection and Warning System, for U.S. marketing in 2016. The FDA first received the marketing-clearance application in late 2014, said Dr. Cavazos, an epileptologist and professor of neurology at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

But Dr. Cavazos also conceded that receiving FDA clearance for U.S. sale of the device is just the next step in an ongoing process to prove its clinical value.

“Currently, clinical decisions for epilepsy patients are often based on patient-reported seizure counts. There is a clear need for objective data on seizure frequency,” something now obtainable only by running an expensive visual-monitoring study, said Dr. Cavazos, who is also founder of and a stockholder in the company that is developing this device. “We definitely need to show in future studies that monitoring [with the worn device] has a positive impact on patient care, by reducing hospitalizations and producing improved patient outcomes,” he said in an interview. “These data may be enough to get regulatory clearance to sell the device, but insurers may not want to reimburse for it until we can prove its value.”

When the device detects a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, it produces an audible alert and also starts recording both surface EMG data and local audible sounds for use in future analysis of the patient’s status. In the study, seizure detection occurred an average of 14 seconds following seizure onset as judged by visual EEG monitoring adjudicated by three epileptologists. The study also included an additional 31 patients who initially entered the study and began wearing the device but did not complete the monitoring protocol because of an adverse effect while wearing the monitor, usually mild or moderate skin irritation.

The results from this study come in a context of extensive research efforts aimed trying to find reliable and unobtrusive methods to quickly detect seizures short of running an observational study. The best results so far have come when using devices that monitor brain EEG signals with electrode-containing caps or implanted electrodes. But patients have voiced substantially reduced interest in having to resort to such stigmatizing methods, noted Dr. Elizabeth Donner during a separate talk at the meeting.

“Patients don’t want what looks like an EEG-detection device. We need devices that suit our patients’ needs,” said Dr. Donner, an epileptologist at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Aside from direct measurement of EEG, other approaches involve measurement of heart rate or movement, she noted.

“There are very good techniques for detecting seizures without using EEG,” said Dr. Gregory L. Krauss, a professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who joined Dr. Donner in a discussion of the pros and cons of current methods for seizure detection. He specifically cited a heart-rate based detection scheme reported last year by a Belgian team (Seizure. 2015 Nov;[32]:52-61). But like all detection methods, the heart rate–based approach showed a marked trade-off between sensitivity and specificity: A heart-rate threshold of at least 50% above baseline had a sensitivity of 82% while identifying one false positive every hour. Raising the detection threshold to at least 30% above baseline boosted the sensitivity to 91%, but with the cost of flagging 3.5 false positives each hour.

Dr. Krauss is currently trying to develop a motion-based approach to identifying seizure onset using an Apple watch, He concluded that, as of now, development of seizure-detection devices that do not rely on direct measurement of brain EEG patterns remains a work in progress, with no prospectively collected data, although he made this assessment prior to the poster report by Dr. Cavazos at the meeting.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT AES 2015

Key clinical point: A seizure-detection device worn on the arm showed good sensitivity and reasonable specificity, but no data yet exist on its clinical utility.

Major finding: The Brain Sentinel device had 100% sensitivity while resulting in 1.47 false-positive alarms every 24 hours.

Data source: The pivotal trial for the Brain Sentinel device, which collected detection data from 142 adults and children with a history of seizures.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Brain Sentinel, which is developing the device. Dr. Cavazos is a founder of the company, holds stock in the company and is a consultant to the company. Dr. Donner had no disclosures. Dr. Krauss has been a consultant to SK Life Science, Acorda Therapeutics, and Sunovion and has received research support from Upsher-Smith, SK Life Science, UCB, Novartis, and Pfizer.

AES: Seizure freedom attainable for most epilepsy patients

PHILADELPHIA - Fully optimized antiepilepsy therapy that tries at least a couple of well-chosen and properly dosed antiseizure drugs as well as follow-up with nondrug options for patients who are unresponsive to pharmaceuticals seems able to render about 80%-90% of epilepsy patients seizure free, Dr. Cynthia L. Harden said while summing up a session on epilepsy therapy at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Finding an appropriate and effective treatment for each epilepsy patient can be “labor intensive and expensive”; it depends in part on a patient’s mood, psychosocial profile, and willingness to comply with treatment; and it often needs the multidisciplinary expertise found at epilepsy centers. But the optimistic message from contemporary seizure-management is that by using a drug or two and in selected patients surgery, diet, or an implanted device, the vast majority of epilepsy patients can become seizure free, noted Dr. Harden, system director of clinical epilepsy services at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York and cochair of the session.

“How many of your uncontrolled patients can become seizure free with more vigilance and tender loving care?” she asked the large audience as she concluded the session. A significant fraction of uncontrolled patients become seizure free when their drug dosage is increased, another drug is substituted or added, their compliance improves, their depression diminishes, or a patient’s understanding of their epilepsy and treatment increases through education, Dr. Harden said.

Drugs remain the cornerstone of seizure control for epilepsy patients, with at least 22 agents now available for epilepsy treatment, including 13 with U.S. or European (or both) approval for initial monotherapy of epilepsy. In addition, study results have shown several agents – carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, and zonisamide – to be more or less equally effective for treating newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, which means that clinicians must also consider factors beyond just efficacy, such as adverse effects, impact on a specific patient’s comorbidities, interactions with other drugs a patient takes, and ease of use and cost, said Dr. Emilio Perucca, a neurologist and professor of pharmacology at the University of Pavia (Italy). In general, newer antiepilepsy drugs have not been more effective than older drugs, he noted.

Another feature of drug treatment is that more is usually not better. “Most patients do not need the highest tolerated dosage,” he said, and minimizing dosages to the lowest effective level helps minimize adverse effects. On the other hand, an antiepilepsy drug needs to be administered at an adequate dosage before concluding that it is ineffective for a patient.

Although a majority of patients respond to the first or second antiepilepsy agent they receive, drugs can’t render all patients seizure free. Results from several reported cohorts show that about 45% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy respond well to the first drug they receive and about 13% become seizure free on a second drug. After that, the response rates fall off sharply, with roughly 5% of patients responding to a third drug or drug combinations, said Dr. Patrick Kwan, professor and chairman of neurology at the University of Melbourne and head of epilepsy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. “Once a patient has failed two drugs, even if they become seizure free on a subsequent drug, there is a higher rate of relapse,” Dr. Kwan noted.

In general, 60%-65% of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients become seizure free with drug monotherapy, Dr. Kwan summarized. Epilepsy patients who fail to fully respond to the first two antiepilepsy drugs they receive need “prompt” referral to an epilepsy center. A “substantial proportion” of patients like this can become seizure free by further optimization of the dosage they receive or by addressing compliance issues, Dr. Kwan said. In addition, some patients achieve full or partial seizure freedom through multidrug treatment or with other treatments.

Two-drug combinations have generally been more effective than combinations with three or more drugs, said Dr. Josiane LaJoie, a pediatric neurologist at New York University. “Using three or more drugs probably won’t lead to better control, just more adverse events,” she cautioned. Many published study results have documented successful two-drug combinations, such as lamotrigine and valproate, and valproate and clobazam, to name just two combinations. In addition to looking at combinations with successful track records in published studies, she highlighted the importance of combining drugs with distinct mechanisms of action and avoiding combing drugs with similar adverse-event profiles. Combinations also need to be tailored to each patient’s clinical characteristics, taking possible drug-drug interactions into account, Dr. LaJoie said.

When drug treatment fails to produce seizure freedom, other options are resective or ablative surgery, diet, or a neurostimulation implant. “At no time in history have we had as many nonpharmacologic treatment options as we have today,” said Dr. Christopher T. Skidmore, a neurologist in the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “With diet or neurostimulation, you get seizure reduction without the adverse effects of addition additional drugs.”

Study results with three different diets indicate that they can each produce a roughly 50% cut in seizure rate in about half the patients who adhere to the diet. The ketogenic diet has the longest track record, but with a 90% fat content, it is notoriously difficult to stick with and requires that patients eat meals that often preclude eating with friends or family members or away from home. Adhering to a modified Atkins diet or a low glycemic load diet seems about as effective as a ketogenic diet while offering more food flexibility and a range of foods more compatible with group meals or meals outside the home, Dr. Skidmore said.

Even though the modified Atkins and low glycemic load diets offer somewhat more flexibility, both remain a “paradigm shift in food consumption,” compared with what most Americans eat, and when compliance is poor they don’t work. “Diet doesn’t work when people cheat,” Dr. Skidmore noted.

Three forms of nerve stimulation have also shown efficacy for seizure reduction, he said: vagal nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. “All three devices have proven efficacy,” he noted. “Neurostimulation offers an alternative to medical therapy that does not require daily effort and compliance.”

Discussions with patients about diet, neurostimulation, and surgery options allow each patient to decide whether one or more of these might be a good option. “It takes a certain patient to follow a diet or want an implant,” he said. “There is no one right choice. You need to educate patients and help them make their choice,” Dr. Skidmore advised.

Dr. Harmon had no disclosures. Dr. Perucca has served as a consultant to and received honoraria from Biopharma Solutions, GW Pharma, Takeda, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Kwan has been a consultant to Eisai and Novartis and has received research funding from UCB. Dr. LaJoie had no disclosures. Dr. Skidmore has been a consultant to Supernus and a site principal investigator for NeuroPace.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA - Fully optimized antiepilepsy therapy that tries at least a couple of well-chosen and properly dosed antiseizure drugs as well as follow-up with nondrug options for patients who are unresponsive to pharmaceuticals seems able to render about 80%-90% of epilepsy patients seizure free, Dr. Cynthia L. Harden said while summing up a session on epilepsy therapy at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Finding an appropriate and effective treatment for each epilepsy patient can be “labor intensive and expensive”; it depends in part on a patient’s mood, psychosocial profile, and willingness to comply with treatment; and it often needs the multidisciplinary expertise found at epilepsy centers. But the optimistic message from contemporary seizure-management is that by using a drug or two and in selected patients surgery, diet, or an implanted device, the vast majority of epilepsy patients can become seizure free, noted Dr. Harden, system director of clinical epilepsy services at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York and cochair of the session.

“How many of your uncontrolled patients can become seizure free with more vigilance and tender loving care?” she asked the large audience as she concluded the session. A significant fraction of uncontrolled patients become seizure free when their drug dosage is increased, another drug is substituted or added, their compliance improves, their depression diminishes, or a patient’s understanding of their epilepsy and treatment increases through education, Dr. Harden said.

Drugs remain the cornerstone of seizure control for epilepsy patients, with at least 22 agents now available for epilepsy treatment, including 13 with U.S. or European (or both) approval for initial monotherapy of epilepsy. In addition, study results have shown several agents – carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, and zonisamide – to be more or less equally effective for treating newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, which means that clinicians must also consider factors beyond just efficacy, such as adverse effects, impact on a specific patient’s comorbidities, interactions with other drugs a patient takes, and ease of use and cost, said Dr. Emilio Perucca, a neurologist and professor of pharmacology at the University of Pavia (Italy). In general, newer antiepilepsy drugs have not been more effective than older drugs, he noted.

Another feature of drug treatment is that more is usually not better. “Most patients do not need the highest tolerated dosage,” he said, and minimizing dosages to the lowest effective level helps minimize adverse effects. On the other hand, an antiepilepsy drug needs to be administered at an adequate dosage before concluding that it is ineffective for a patient.

Although a majority of patients respond to the first or second antiepilepsy agent they receive, drugs can’t render all patients seizure free. Results from several reported cohorts show that about 45% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy respond well to the first drug they receive and about 13% become seizure free on a second drug. After that, the response rates fall off sharply, with roughly 5% of patients responding to a third drug or drug combinations, said Dr. Patrick Kwan, professor and chairman of neurology at the University of Melbourne and head of epilepsy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. “Once a patient has failed two drugs, even if they become seizure free on a subsequent drug, there is a higher rate of relapse,” Dr. Kwan noted.

In general, 60%-65% of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients become seizure free with drug monotherapy, Dr. Kwan summarized. Epilepsy patients who fail to fully respond to the first two antiepilepsy drugs they receive need “prompt” referral to an epilepsy center. A “substantial proportion” of patients like this can become seizure free by further optimization of the dosage they receive or by addressing compliance issues, Dr. Kwan said. In addition, some patients achieve full or partial seizure freedom through multidrug treatment or with other treatments.

Two-drug combinations have generally been more effective than combinations with three or more drugs, said Dr. Josiane LaJoie, a pediatric neurologist at New York University. “Using three or more drugs probably won’t lead to better control, just more adverse events,” she cautioned. Many published study results have documented successful two-drug combinations, such as lamotrigine and valproate, and valproate and clobazam, to name just two combinations. In addition to looking at combinations with successful track records in published studies, she highlighted the importance of combining drugs with distinct mechanisms of action and avoiding combing drugs with similar adverse-event profiles. Combinations also need to be tailored to each patient’s clinical characteristics, taking possible drug-drug interactions into account, Dr. LaJoie said.

When drug treatment fails to produce seizure freedom, other options are resective or ablative surgery, diet, or a neurostimulation implant. “At no time in history have we had as many nonpharmacologic treatment options as we have today,” said Dr. Christopher T. Skidmore, a neurologist in the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “With diet or neurostimulation, you get seizure reduction without the adverse effects of addition additional drugs.”

Study results with three different diets indicate that they can each produce a roughly 50% cut in seizure rate in about half the patients who adhere to the diet. The ketogenic diet has the longest track record, but with a 90% fat content, it is notoriously difficult to stick with and requires that patients eat meals that often preclude eating with friends or family members or away from home. Adhering to a modified Atkins diet or a low glycemic load diet seems about as effective as a ketogenic diet while offering more food flexibility and a range of foods more compatible with group meals or meals outside the home, Dr. Skidmore said.

Even though the modified Atkins and low glycemic load diets offer somewhat more flexibility, both remain a “paradigm shift in food consumption,” compared with what most Americans eat, and when compliance is poor they don’t work. “Diet doesn’t work when people cheat,” Dr. Skidmore noted.

Three forms of nerve stimulation have also shown efficacy for seizure reduction, he said: vagal nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. “All three devices have proven efficacy,” he noted. “Neurostimulation offers an alternative to medical therapy that does not require daily effort and compliance.”

Discussions with patients about diet, neurostimulation, and surgery options allow each patient to decide whether one or more of these might be a good option. “It takes a certain patient to follow a diet or want an implant,” he said. “There is no one right choice. You need to educate patients and help them make their choice,” Dr. Skidmore advised.

Dr. Harmon had no disclosures. Dr. Perucca has served as a consultant to and received honoraria from Biopharma Solutions, GW Pharma, Takeda, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Kwan has been a consultant to Eisai and Novartis and has received research funding from UCB. Dr. LaJoie had no disclosures. Dr. Skidmore has been a consultant to Supernus and a site principal investigator for NeuroPace.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA - Fully optimized antiepilepsy therapy that tries at least a couple of well-chosen and properly dosed antiseizure drugs as well as follow-up with nondrug options for patients who are unresponsive to pharmaceuticals seems able to render about 80%-90% of epilepsy patients seizure free, Dr. Cynthia L. Harden said while summing up a session on epilepsy therapy at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Finding an appropriate and effective treatment for each epilepsy patient can be “labor intensive and expensive”; it depends in part on a patient’s mood, psychosocial profile, and willingness to comply with treatment; and it often needs the multidisciplinary expertise found at epilepsy centers. But the optimistic message from contemporary seizure-management is that by using a drug or two and in selected patients surgery, diet, or an implanted device, the vast majority of epilepsy patients can become seizure free, noted Dr. Harden, system director of clinical epilepsy services at the Mount Sinai Health System in New York and cochair of the session.

“How many of your uncontrolled patients can become seizure free with more vigilance and tender loving care?” she asked the large audience as she concluded the session. A significant fraction of uncontrolled patients become seizure free when their drug dosage is increased, another drug is substituted or added, their compliance improves, their depression diminishes, or a patient’s understanding of their epilepsy and treatment increases through education, Dr. Harden said.

Drugs remain the cornerstone of seizure control for epilepsy patients, with at least 22 agents now available for epilepsy treatment, including 13 with U.S. or European (or both) approval for initial monotherapy of epilepsy. In addition, study results have shown several agents – carbamazepine, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, and zonisamide – to be more or less equally effective for treating newly diagnosed focal epilepsy, which means that clinicians must also consider factors beyond just efficacy, such as adverse effects, impact on a specific patient’s comorbidities, interactions with other drugs a patient takes, and ease of use and cost, said Dr. Emilio Perucca, a neurologist and professor of pharmacology at the University of Pavia (Italy). In general, newer antiepilepsy drugs have not been more effective than older drugs, he noted.

Another feature of drug treatment is that more is usually not better. “Most patients do not need the highest tolerated dosage,” he said, and minimizing dosages to the lowest effective level helps minimize adverse effects. On the other hand, an antiepilepsy drug needs to be administered at an adequate dosage before concluding that it is ineffective for a patient.

Although a majority of patients respond to the first or second antiepilepsy agent they receive, drugs can’t render all patients seizure free. Results from several reported cohorts show that about 45% of patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy respond well to the first drug they receive and about 13% become seizure free on a second drug. After that, the response rates fall off sharply, with roughly 5% of patients responding to a third drug or drug combinations, said Dr. Patrick Kwan, professor and chairman of neurology at the University of Melbourne and head of epilepsy at Royal Melbourne Hospital. “Once a patient has failed two drugs, even if they become seizure free on a subsequent drug, there is a higher rate of relapse,” Dr. Kwan noted.

In general, 60%-65% of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients become seizure free with drug monotherapy, Dr. Kwan summarized. Epilepsy patients who fail to fully respond to the first two antiepilepsy drugs they receive need “prompt” referral to an epilepsy center. A “substantial proportion” of patients like this can become seizure free by further optimization of the dosage they receive or by addressing compliance issues, Dr. Kwan said. In addition, some patients achieve full or partial seizure freedom through multidrug treatment or with other treatments.

Two-drug combinations have generally been more effective than combinations with three or more drugs, said Dr. Josiane LaJoie, a pediatric neurologist at New York University. “Using three or more drugs probably won’t lead to better control, just more adverse events,” she cautioned. Many published study results have documented successful two-drug combinations, such as lamotrigine and valproate, and valproate and clobazam, to name just two combinations. In addition to looking at combinations with successful track records in published studies, she highlighted the importance of combining drugs with distinct mechanisms of action and avoiding combing drugs with similar adverse-event profiles. Combinations also need to be tailored to each patient’s clinical characteristics, taking possible drug-drug interactions into account, Dr. LaJoie said.

When drug treatment fails to produce seizure freedom, other options are resective or ablative surgery, diet, or a neurostimulation implant. “At no time in history have we had as many nonpharmacologic treatment options as we have today,” said Dr. Christopher T. Skidmore, a neurologist in the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. “With diet or neurostimulation, you get seizure reduction without the adverse effects of addition additional drugs.”

Study results with three different diets indicate that they can each produce a roughly 50% cut in seizure rate in about half the patients who adhere to the diet. The ketogenic diet has the longest track record, but with a 90% fat content, it is notoriously difficult to stick with and requires that patients eat meals that often preclude eating with friends or family members or away from home. Adhering to a modified Atkins diet or a low glycemic load diet seems about as effective as a ketogenic diet while offering more food flexibility and a range of foods more compatible with group meals or meals outside the home, Dr. Skidmore said.

Even though the modified Atkins and low glycemic load diets offer somewhat more flexibility, both remain a “paradigm shift in food consumption,” compared with what most Americans eat, and when compliance is poor they don’t work. “Diet doesn’t work when people cheat,” Dr. Skidmore noted.

Three forms of nerve stimulation have also shown efficacy for seizure reduction, he said: vagal nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation of the anterior nucleus of the thalamus. “All three devices have proven efficacy,” he noted. “Neurostimulation offers an alternative to medical therapy that does not require daily effort and compliance.”

Discussions with patients about diet, neurostimulation, and surgery options allow each patient to decide whether one or more of these might be a good option. “It takes a certain patient to follow a diet or want an implant,” he said. “There is no one right choice. You need to educate patients and help them make their choice,” Dr. Skidmore advised.

Dr. Harmon had no disclosures. Dr. Perucca has served as a consultant to and received honoraria from Biopharma Solutions, GW Pharma, Takeda, Sun Pharma, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Kwan has been a consultant to Eisai and Novartis and has received research funding from UCB. Dr. LaJoie had no disclosures. Dr. Skidmore has been a consultant to Supernus and a site principal investigator for NeuroPace.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AES 2015

AES: Sparse evidence hints at epilepsy disease modification

PHILADELPHIA – Tantalizing hints support the possibility that disease modification of epilepsy is possible, but while the best evidence available today for disease modification may be “very encouraging and strongly suggestive,” it also remains low-level evidence drawn from modest numbers of patients, Dr. Andrew J. Cole said during the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The upshot is that proving disease modification is feasible for some epilepsy types “stands to be a great challenge for a long time to come,” said Dr. Cole, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Dr. Cole started by defining disease modification: A treatment that modifies a disease’s expression, course, severity or duration, or modifies comorbidities integral to the disease. These effects need not be mutually exclusive, he added. Another issue about disease modification is that it presumably takes a long time to happen, which makes it harder to recognize. “Disease modification likely happens over the long term, which produces a severe methodological challenge,” Dr. Cole said.

Perhaps the best example of what appears to be disease modification of epilepsy are the long-term outcomes of patients with severe disease – 30 or more seizures a month – who receive long-term treatment with deep brain stimulation (DBS). These patients “seem to get better and better over several years [of treatment], as if their disease was changing,” he said.

For example, both the short- and long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in the Stimulation of the Anterior Nucleus of the Thalamus for Epilepsy (SANTE) trial, which enrolled 157 patients, showed that over time continued DBS linked with a steady decrease in seizure numbers. Recently published long-term follow-up results showed that seizure reduction grew from an average drop of 41% from baseline numbers after 1 year of DBS to an average reduction from baseline of 69% after 5 years (Neurology. 2015 Mar 10;84[10]:1017-25).

A similar pattern of this DBS effect came in 2-year follow-up results from the 191-patient pivotal trial for the responsive neurostimulation system, which showed a 44% reduction, compared with baseline in seizure incidence after 1 year and a 53% reduction after 2 years (Epilepsia. 2014 March;55[3]:432-41). Once again, the findings suggest “a plasticity response and not a purely symptomatic response,” Dr. Cole said.

He also cited findings from two additional, much smaller series of patients who stopped prolonged treatment with DBS and continued to have low seizure rates, compared with the incidence before DBS began. In short, observations from several series of patients who underwent DBS make a “reasonable case for disease modification by suggesting disease modification can occur,” Dr. Cole said.

He cited two additional lines of evidence: a rat model of early treatment for spike-wave epilepsy (Epilepsia. 2008 Mar;49[3]:400-9), and studies of patients with epileptic encephalopathy that have shown associations between early treatment and better cognitive outcomes regardless of the type of treatment patients received (Epilepsia. 2015 Oct;56[10]:1482-5). One limitation of the epileptic encephalopathy examples is the difficulty, if not impossibility. of conducting randomized trials to truly test the hypothesis that treatment can be disease modifying. “The big problem is distinguishing an anticonvulsant effect of treatment from a disease-modifying antiepileptogenic effect,” Dr. Cole said.

He proposed a clinical setting where it’s possible to envision a randomized clinical trial that could test whether a disease-modifying effect occurs: Prophylactic treatment of people who have experienced brain insults known to potentially trigger epilepsy, such as head trauma or stroke. So far, this approach has not been used to test possible disease-modifying treatments. Although such studies are plausible they would also be limited by the number of patients required to produce statistically meaningful results.

Dr. Cole estimated that based on assumptions of epilepsy incidence following various types of brain insults and the possible efficacy of a disease-modifying intervention, such trials could require anywhere from several hundred to several thousand patients, with price tags ranging from more than $10 million to more than $100 million per study. Plus, “even if we had success, [the treatment] would be relevant to a relatively small fraction of patients with epilepsy,” he said.

Dr. Cole said that he has been a consultant to Precisis, NeuroPace, and Nestec.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Tantalizing hints support the possibility that disease modification of epilepsy is possible, but while the best evidence available today for disease modification may be “very encouraging and strongly suggestive,” it also remains low-level evidence drawn from modest numbers of patients, Dr. Andrew J. Cole said during the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The upshot is that proving disease modification is feasible for some epilepsy types “stands to be a great challenge for a long time to come,” said Dr. Cole, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Dr. Cole started by defining disease modification: A treatment that modifies a disease’s expression, course, severity or duration, or modifies comorbidities integral to the disease. These effects need not be mutually exclusive, he added. Another issue about disease modification is that it presumably takes a long time to happen, which makes it harder to recognize. “Disease modification likely happens over the long term, which produces a severe methodological challenge,” Dr. Cole said.

Perhaps the best example of what appears to be disease modification of epilepsy are the long-term outcomes of patients with severe disease – 30 or more seizures a month – who receive long-term treatment with deep brain stimulation (DBS). These patients “seem to get better and better over several years [of treatment], as if their disease was changing,” he said.

For example, both the short- and long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in the Stimulation of the Anterior Nucleus of the Thalamus for Epilepsy (SANTE) trial, which enrolled 157 patients, showed that over time continued DBS linked with a steady decrease in seizure numbers. Recently published long-term follow-up results showed that seizure reduction grew from an average drop of 41% from baseline numbers after 1 year of DBS to an average reduction from baseline of 69% after 5 years (Neurology. 2015 Mar 10;84[10]:1017-25).

A similar pattern of this DBS effect came in 2-year follow-up results from the 191-patient pivotal trial for the responsive neurostimulation system, which showed a 44% reduction, compared with baseline in seizure incidence after 1 year and a 53% reduction after 2 years (Epilepsia. 2014 March;55[3]:432-41). Once again, the findings suggest “a plasticity response and not a purely symptomatic response,” Dr. Cole said.

He also cited findings from two additional, much smaller series of patients who stopped prolonged treatment with DBS and continued to have low seizure rates, compared with the incidence before DBS began. In short, observations from several series of patients who underwent DBS make a “reasonable case for disease modification by suggesting disease modification can occur,” Dr. Cole said.

He cited two additional lines of evidence: a rat model of early treatment for spike-wave epilepsy (Epilepsia. 2008 Mar;49[3]:400-9), and studies of patients with epileptic encephalopathy that have shown associations between early treatment and better cognitive outcomes regardless of the type of treatment patients received (Epilepsia. 2015 Oct;56[10]:1482-5). One limitation of the epileptic encephalopathy examples is the difficulty, if not impossibility. of conducting randomized trials to truly test the hypothesis that treatment can be disease modifying. “The big problem is distinguishing an anticonvulsant effect of treatment from a disease-modifying antiepileptogenic effect,” Dr. Cole said.

He proposed a clinical setting where it’s possible to envision a randomized clinical trial that could test whether a disease-modifying effect occurs: Prophylactic treatment of people who have experienced brain insults known to potentially trigger epilepsy, such as head trauma or stroke. So far, this approach has not been used to test possible disease-modifying treatments. Although such studies are plausible they would also be limited by the number of patients required to produce statistically meaningful results.

Dr. Cole estimated that based on assumptions of epilepsy incidence following various types of brain insults and the possible efficacy of a disease-modifying intervention, such trials could require anywhere from several hundred to several thousand patients, with price tags ranging from more than $10 million to more than $100 million per study. Plus, “even if we had success, [the treatment] would be relevant to a relatively small fraction of patients with epilepsy,” he said.

Dr. Cole said that he has been a consultant to Precisis, NeuroPace, and Nestec.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Tantalizing hints support the possibility that disease modification of epilepsy is possible, but while the best evidence available today for disease modification may be “very encouraging and strongly suggestive,” it also remains low-level evidence drawn from modest numbers of patients, Dr. Andrew J. Cole said during the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The upshot is that proving disease modification is feasible for some epilepsy types “stands to be a great challenge for a long time to come,” said Dr. Cole, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and director of the epilepsy service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

Dr. Cole started by defining disease modification: A treatment that modifies a disease’s expression, course, severity or duration, or modifies comorbidities integral to the disease. These effects need not be mutually exclusive, he added. Another issue about disease modification is that it presumably takes a long time to happen, which makes it harder to recognize. “Disease modification likely happens over the long term, which produces a severe methodological challenge,” Dr. Cole said.

Perhaps the best example of what appears to be disease modification of epilepsy are the long-term outcomes of patients with severe disease – 30 or more seizures a month – who receive long-term treatment with deep brain stimulation (DBS). These patients “seem to get better and better over several years [of treatment], as if their disease was changing,” he said.

For example, both the short- and long-term follow-up of patients enrolled in the Stimulation of the Anterior Nucleus of the Thalamus for Epilepsy (SANTE) trial, which enrolled 157 patients, showed that over time continued DBS linked with a steady decrease in seizure numbers. Recently published long-term follow-up results showed that seizure reduction grew from an average drop of 41% from baseline numbers after 1 year of DBS to an average reduction from baseline of 69% after 5 years (Neurology. 2015 Mar 10;84[10]:1017-25).

A similar pattern of this DBS effect came in 2-year follow-up results from the 191-patient pivotal trial for the responsive neurostimulation system, which showed a 44% reduction, compared with baseline in seizure incidence after 1 year and a 53% reduction after 2 years (Epilepsia. 2014 March;55[3]:432-41). Once again, the findings suggest “a plasticity response and not a purely symptomatic response,” Dr. Cole said.

He also cited findings from two additional, much smaller series of patients who stopped prolonged treatment with DBS and continued to have low seizure rates, compared with the incidence before DBS began. In short, observations from several series of patients who underwent DBS make a “reasonable case for disease modification by suggesting disease modification can occur,” Dr. Cole said.

He cited two additional lines of evidence: a rat model of early treatment for spike-wave epilepsy (Epilepsia. 2008 Mar;49[3]:400-9), and studies of patients with epileptic encephalopathy that have shown associations between early treatment and better cognitive outcomes regardless of the type of treatment patients received (Epilepsia. 2015 Oct;56[10]:1482-5). One limitation of the epileptic encephalopathy examples is the difficulty, if not impossibility. of conducting randomized trials to truly test the hypothesis that treatment can be disease modifying. “The big problem is distinguishing an anticonvulsant effect of treatment from a disease-modifying antiepileptogenic effect,” Dr. Cole said.

He proposed a clinical setting where it’s possible to envision a randomized clinical trial that could test whether a disease-modifying effect occurs: Prophylactic treatment of people who have experienced brain insults known to potentially trigger epilepsy, such as head trauma or stroke. So far, this approach has not been used to test possible disease-modifying treatments. Although such studies are plausible they would also be limited by the number of patients required to produce statistically meaningful results.

Dr. Cole estimated that based on assumptions of epilepsy incidence following various types of brain insults and the possible efficacy of a disease-modifying intervention, such trials could require anywhere from several hundred to several thousand patients, with price tags ranging from more than $10 million to more than $100 million per study. Plus, “even if we had success, [the treatment] would be relevant to a relatively small fraction of patients with epilepsy,” he said.

Dr. Cole said that he has been a consultant to Precisis, NeuroPace, and Nestec.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AES 2015

Good luck convincing patients that generics equal brand-name drugs

Generic drugs have long carried a stigma for at least some people. Patients sometimes feel scared and shortchanged when prescribed them, and some physicians have been wary of their safety and efficacy, compared with brand-name counterparts.

This fall, results appeared from a trio of prospective, randomized studies that compared several generic forms of the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine against the brand-name compound, Lamictal, in patients with epilepsy. As reported earlier this month in a special session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, and as I wrote up in a news article, the findings from all three studies consistently and clearly showed that the generic lamotrigine products tested in these three studies all performed identically to Lamictal by both their pharmacokinetic profiles and in their clinical safety and efficacy.

A critic could quibble that the three studies involved relatively small numbers of patients (they included 34-48 subjects), that the treatment times were relatively brief (a matter of a few weeks), and the investigations were limited to just lamotrigine. But the neurologists who reported these findings, a pair of Food and Drug Administration staffers who deal with generics and spoke at the session, and two pharmacy researchers who also participated in the panel all agreed that these groundbreaking studies establish an unprecedented level of confidence in not just the generic products tested but for generic drugs in general.

As Dr. Michael Privitera, director of the Epilepsy Center at the University of Cincinnati and a lead investigator for two of the three studies, told me, controlling seizures in epilepsy patients is a stringent test of drug efficacy and similarity. If generic forms of lamotrigine behave indistinguishably from Lamictal, then it’s very reasonable to expect that virtually any generic form of any brand-name drug used in medicine is also a good mimic if it recently passed FDA muster. His only caveat was selected drugs with very unusual pharmacokinetic properties, such as phenytoin – another antiepileptic drug, which has saturation kinetics making it a special case that requires additional, customized testing to prove equivalence between the generic and brand-name form.

But as he and others at the session highlighted, equivalent pharmacologic properties of generic and brand-name forms of a drug tell just part of the story. They may act the same once inside patients’ bodies, but what’s also important is how patients regard these drugs from the neck up. Psychological factors play a role in how patients perceive and use different forms of chemically identical products. Differences in pill size, shape, and color can confuse patients, and just knowing that a drug is a generic could possibly trigger anxiety in a patient that might perhaps produce a seizure or disrupt their pill-taking behavior. Several clinicians at the session spoke of certain patients who have begged them to specify the brand-name drug on their prescriptions. On the other hand, a generic’s lower price often encourages more conscientious use, a phenomenon documented in a database review reported at the session by pharmacoepidemiologist Joshua J. Gagne, Pharm.D.

Madison Avenue has known for years that function and utility tell just part of the story when it comes to consumer goods. A Kia may be just as durable and effective for transporting someone as a Mercedes or BMW, but cheap isn’t always what a consumer wants or feels comfortable with. Generics that work indistinguishably from brand drugs are certainly attractive for the U.S. health care system and the majority of the American public, but the concept that generic is best will be tough to sell to everyone.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Generic drugs have long carried a stigma for at least some people. Patients sometimes feel scared and shortchanged when prescribed them, and some physicians have been wary of their safety and efficacy, compared with brand-name counterparts.

This fall, results appeared from a trio of prospective, randomized studies that compared several generic forms of the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine against the brand-name compound, Lamictal, in patients with epilepsy. As reported earlier this month in a special session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, and as I wrote up in a news article, the findings from all three studies consistently and clearly showed that the generic lamotrigine products tested in these three studies all performed identically to Lamictal by both their pharmacokinetic profiles and in their clinical safety and efficacy.

A critic could quibble that the three studies involved relatively small numbers of patients (they included 34-48 subjects), that the treatment times were relatively brief (a matter of a few weeks), and the investigations were limited to just lamotrigine. But the neurologists who reported these findings, a pair of Food and Drug Administration staffers who deal with generics and spoke at the session, and two pharmacy researchers who also participated in the panel all agreed that these groundbreaking studies establish an unprecedented level of confidence in not just the generic products tested but for generic drugs in general.

As Dr. Michael Privitera, director of the Epilepsy Center at the University of Cincinnati and a lead investigator for two of the three studies, told me, controlling seizures in epilepsy patients is a stringent test of drug efficacy and similarity. If generic forms of lamotrigine behave indistinguishably from Lamictal, then it’s very reasonable to expect that virtually any generic form of any brand-name drug used in medicine is also a good mimic if it recently passed FDA muster. His only caveat was selected drugs with very unusual pharmacokinetic properties, such as phenytoin – another antiepileptic drug, which has saturation kinetics making it a special case that requires additional, customized testing to prove equivalence between the generic and brand-name form.

But as he and others at the session highlighted, equivalent pharmacologic properties of generic and brand-name forms of a drug tell just part of the story. They may act the same once inside patients’ bodies, but what’s also important is how patients regard these drugs from the neck up. Psychological factors play a role in how patients perceive and use different forms of chemically identical products. Differences in pill size, shape, and color can confuse patients, and just knowing that a drug is a generic could possibly trigger anxiety in a patient that might perhaps produce a seizure or disrupt their pill-taking behavior. Several clinicians at the session spoke of certain patients who have begged them to specify the brand-name drug on their prescriptions. On the other hand, a generic’s lower price often encourages more conscientious use, a phenomenon documented in a database review reported at the session by pharmacoepidemiologist Joshua J. Gagne, Pharm.D.

Madison Avenue has known for years that function and utility tell just part of the story when it comes to consumer goods. A Kia may be just as durable and effective for transporting someone as a Mercedes or BMW, but cheap isn’t always what a consumer wants or feels comfortable with. Generics that work indistinguishably from brand drugs are certainly attractive for the U.S. health care system and the majority of the American public, but the concept that generic is best will be tough to sell to everyone.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Generic drugs have long carried a stigma for at least some people. Patients sometimes feel scared and shortchanged when prescribed them, and some physicians have been wary of their safety and efficacy, compared with brand-name counterparts.

This fall, results appeared from a trio of prospective, randomized studies that compared several generic forms of the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine against the brand-name compound, Lamictal, in patients with epilepsy. As reported earlier this month in a special session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, and as I wrote up in a news article, the findings from all three studies consistently and clearly showed that the generic lamotrigine products tested in these three studies all performed identically to Lamictal by both their pharmacokinetic profiles and in their clinical safety and efficacy.

A critic could quibble that the three studies involved relatively small numbers of patients (they included 34-48 subjects), that the treatment times were relatively brief (a matter of a few weeks), and the investigations were limited to just lamotrigine. But the neurologists who reported these findings, a pair of Food and Drug Administration staffers who deal with generics and spoke at the session, and two pharmacy researchers who also participated in the panel all agreed that these groundbreaking studies establish an unprecedented level of confidence in not just the generic products tested but for generic drugs in general.

As Dr. Michael Privitera, director of the Epilepsy Center at the University of Cincinnati and a lead investigator for two of the three studies, told me, controlling seizures in epilepsy patients is a stringent test of drug efficacy and similarity. If generic forms of lamotrigine behave indistinguishably from Lamictal, then it’s very reasonable to expect that virtually any generic form of any brand-name drug used in medicine is also a good mimic if it recently passed FDA muster. His only caveat was selected drugs with very unusual pharmacokinetic properties, such as phenytoin – another antiepileptic drug, which has saturation kinetics making it a special case that requires additional, customized testing to prove equivalence between the generic and brand-name form.

But as he and others at the session highlighted, equivalent pharmacologic properties of generic and brand-name forms of a drug tell just part of the story. They may act the same once inside patients’ bodies, but what’s also important is how patients regard these drugs from the neck up. Psychological factors play a role in how patients perceive and use different forms of chemically identical products. Differences in pill size, shape, and color can confuse patients, and just knowing that a drug is a generic could possibly trigger anxiety in a patient that might perhaps produce a seizure or disrupt their pill-taking behavior. Several clinicians at the session spoke of certain patients who have begged them to specify the brand-name drug on their prescriptions. On the other hand, a generic’s lower price often encourages more conscientious use, a phenomenon documented in a database review reported at the session by pharmacoepidemiologist Joshua J. Gagne, Pharm.D.

Madison Avenue has known for years that function and utility tell just part of the story when it comes to consumer goods. A Kia may be just as durable and effective for transporting someone as a Mercedes or BMW, but cheap isn’t always what a consumer wants or feels comfortable with. Generics that work indistinguishably from brand drugs are certainly attractive for the U.S. health care system and the majority of the American public, but the concept that generic is best will be tough to sell to everyone.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AES: Three studies show generic lamotrigine equals Lamictal

PHILADELPHIA – Several different generic lamotrigine products proved pharmacologically and clinically equivalent to Lamictal, the brand-name, reference form of lamotrigine, in three separate, prospective, randomized trials run by two independent groups. These results that should lay to rest lingering concerns by physicians and patients that generic lamotrigine poses any risk to patients, agreed a panel of experts speaking at a session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The findings, which confirmed the standards now set by the Food and Drug Administration for deeming generic products equivalent to their reference product, should also reassure physicians and patients more broadly about the reliability of the generic forms of most other antiepileptic drugs as well as generic drugs used for virtually all indications across the range of medical practice, the panelists said.

The results of these three new studies “show that generic drugs have the same quality as the reference-listed drugs in patients with epilepsy,” said Dr. Wenlei Jiang, acting deputy director of the FDA’s Office of Research Standards and Office of Generic Drugs. Dr. Jiang coauthored one of the new studies.

“We were a skeptical group going into our studies,” said Dr. Michael Privitera, coprincipal investigator for the other two new studies. “We were not sure that these drugs [brand-name lamotrigine and various generic products] were really the same. We were shocked at how equivalent they were. It wasn’t that the differences [among their pharmacokinetic profiles] were small; it’s that there was no difference. We could not see any difference,” said Dr. Privitera, professor of neurology and director of the Epilepsy Center at the University of Cincinnati.

“We chose to study lamotrigine because there had been a lot of complaints [about the generic products] and because it is a drug that is very susceptible to drug-drug interactions. There is no reason I can think of why what we found would not extend to all antiepileptic drugs except for phenytoin, which has saturation kinetics and the way the FDA tests drugs in a single-dose study is not appropriate for drugs with saturation kinetics,” Dr. Privitera said in an interview. The implications of the new findings also extend beyond just drugs for epilepsy or other neurologic conditions, he added.

“When you have a very complicated disorder like epilepsy, which has the possibility for drug-drug interactions, and we could show this much quality” in the generic products, it has implications for the entire universe of generic drugs that show equivalence in FDA-mandated testing, Dr. Privitera said.

Randomized trials in epilepsy patients

One of the two studies run by Dr. Privitera and his associates used a single-dose format, and the second used a chronic-dosage format.

The EQUIGEN (Equivalence Among Antiepileptic Drug Generic and Brand Products in People With Epilepsy) Single Dose Study enrolled 48 epilepsy patients at any of six U.S. centers. All patients were on an antiepileptic drug other than lamotrigine, and the researchers randomized them to receive single doses of the brand-name reference form of lamotrigine (Lamictal), or either of two generic forms of lamotrigine. Patients received single dosages of each of the three study drugs with a 12-23 day washout period separating each dose (the preferred washout interval was 14 days), with the patients and researchers blinded to which specific product was administered at any time. The researchers selected the two FDA-approved generic products with the most widely divergent profiles based on in vitro dissolution testing and prior pharmacokinetic data supplied to the FDA. Forty-five patients received the scheduled two doses (on two different occasions) of each drug, a total of six test doses administered. The remaining three patients received a single dose of each of the three tested products.

All three products resulted in essentially superimposed concentration-time curves and area under the curve measures with no outliers or serious adverse events seen, Dr. Privitera and his associates reported in a poster presented at the meeting as well as during the session.

The EQUIGEN Chronic Dose Study compared the pharmacokinetic patterns after chronic dosing for 2 weeks with one of the two most disparate lamotrigine generic products. The study enrolled 35 patients with epilepsy at any of six U.S. centers, and 33 patients completed all four treatment periods, which involved a repeated crossover between the two study products. Patients received lamotrigine twice daily and could be on additional antiepileptic drugs or monotherapy; six patients received concomitant enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs during the study. The results showed that the area under the curve for both products had 90% confidence intervals of 98%-103%, compared with Lamictal, and they both had a 90% confidence interval for peak plasma concentration of 99%-105%, Dr. Privitera and his associates reported at the session. None of the enrolled patients showed unexpected adverse events, and the two generics produced similar adverse-event profiles.

The third study, BEEP (Bioequivalence in Epilepsy Patients) ran at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the results appeared in a journal article published in September (Epilepsia. 2015 Sept;56[9]:1415-24). This study enrolled 34 “generic brittle” epilepsy patients, which meant they had already shown signs of possible sensitivity to switching from Lamictal to generic lamotrigine. The study randomized patients to four consecutive 2-week periods of treatment with either the brand-name or a generic lamotrigine product in a crossover design that was then repeated, and each patient underwent a 12-hour pharmacokinetic analysis after they reached a steady-state drug level with 2 weeks of treatment. The results showed a tight match for both the area under the curve and peak plasma concentration for the generic and brand drugs, said Dr. Tricia Y. Ting, lead investigator for the study and a neurologist and epilepsy specialist at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore.

“The results could not have been more beautiful. We were quite surprised at how close the generic and brand products were” in their steady-state pharmacokinetic profiles, Dr. Ting said during the session.

The results of the three studies, while reassuring, raise questions as to why some patients nevertheless report problems while taking generic products, noted Dr. Ting. “We need to look outside of bioequivalence, and focus instead on issues such as patient expectations,” she said.

Patient factors

Dr. Joshua J. Gagne, a pharmacoepidemiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, discussed the role of patient expectations and other patient-specific factors that can affect the safety and efficacy of generic products. He noted that patients can be confused by generic pills that do not have the same size, shape, or color as their brand-name counterparts. “Variations in appearance with generic antiepilepsy drugs is a real problem and may be a barrier to adherence,” he said. In addition, “patients’ out of pocket costs are important drivers of antiepileptic drug adherence,” and may act in favor of generics, he said.

He documented this potential effect in a recent study he published and also summarized while speaking during the session. Dr. Gagne and his associates used a database of more than 19,000 U.S. Medicare patients with epilepsy who began treatment with an antiepileptic drug. The researchers used propensity scoring to match a subset from among the 18,306 patients who started on a generic drug and the 1,454 patients who started on a brand-name drug. In the matched subgroups, those on a generic went an average of 138 days before having a 14-day gap in treatment, compared with an average 124 days until a 14-day treatment gap occurred among those on a branded drug. This difference in adherence linked with a significant difference in seizure-related hospitalizations, experienced by 47 patients who started on a branded drug and in 31 of those who started on a generic. This calculated out to a statistically significant relative risk reduction of more than 50% (Epilepsy Behavior. 2015 Nov;52[part A]:14-8).

Often it is the physician that’s to blame when patients lack trust in a generic drug, noted Dr. Michel J. Berg, a neurologist at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) and coprincipal investigator on the two EQUIGEN studies. “If physicians are confident [in generics] then patients will rely on the physician’s expert opinion,” Dr. Berg said during a panel discussion of these studies during the session.

Patients and physicians also need to realize that today’s generics are often not the same products that they were years ago. The FDA has “encouraged manufacturers to move from ’quality by testing’ to ‘quality by design,’ which has resulted in better products,” stressed Dr. Jiang.

Dr. Privitera agreed. “A lot of the fear about generics was generated 20 or more years ago, when the generic quality was not as good. There were a lot of scary stories out there. Today, with quality by design, manufacturers don’t just try to get their generic in a target range but they do multiple tests earlier in the [generic development] process so that by the time they get to clinical testing they already have a drug that is really tight.”

Members of the audience at the session who commented during the discussion period usually agreed that the new data reported for lamotrigine convinced them of the quality of modern generics. “There has been discomfort with generics, but now we have the data that they are effective and safe,” commented Dr. Mark C. Spitz, professor of neurology and head of the Adult Comprehensive Epilepsy Program at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, who spoke from the floor. “These new data will make a big difference in how epileptologists will practice,” Dr. Spitz predicted.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

PHILADELPHIA – Several different generic lamotrigine products proved pharmacologically and clinically equivalent to Lamictal, the brand-name, reference form of lamotrigine, in three separate, prospective, randomized trials run by two independent groups. These results that should lay to rest lingering concerns by physicians and patients that generic lamotrigine poses any risk to patients, agreed a panel of experts speaking at a session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The findings, which confirmed the standards now set by the Food and Drug Administration for deeming generic products equivalent to their reference product, should also reassure physicians and patients more broadly about the reliability of the generic forms of most other antiepileptic drugs as well as generic drugs used for virtually all indications across the range of medical practice, the panelists said.

The results of these three new studies “show that generic drugs have the same quality as the reference-listed drugs in patients with epilepsy,” said Dr. Wenlei Jiang, acting deputy director of the FDA’s Office of Research Standards and Office of Generic Drugs. Dr. Jiang coauthored one of the new studies.

“We were a skeptical group going into our studies,” said Dr. Michael Privitera, coprincipal investigator for the other two new studies. “We were not sure that these drugs [brand-name lamotrigine and various generic products] were really the same. We were shocked at how equivalent they were. It wasn’t that the differences [among their pharmacokinetic profiles] were small; it’s that there was no difference. We could not see any difference,” said Dr. Privitera, professor of neurology and director of the Epilepsy Center at the University of Cincinnati.

“We chose to study lamotrigine because there had been a lot of complaints [about the generic products] and because it is a drug that is very susceptible to drug-drug interactions. There is no reason I can think of why what we found would not extend to all antiepileptic drugs except for phenytoin, which has saturation kinetics and the way the FDA tests drugs in a single-dose study is not appropriate for drugs with saturation kinetics,” Dr. Privitera said in an interview. The implications of the new findings also extend beyond just drugs for epilepsy or other neurologic conditions, he added.

“When you have a very complicated disorder like epilepsy, which has the possibility for drug-drug interactions, and we could show this much quality” in the generic products, it has implications for the entire universe of generic drugs that show equivalence in FDA-mandated testing, Dr. Privitera said.

Randomized trials in epilepsy patients

One of the two studies run by Dr. Privitera and his associates used a single-dose format, and the second used a chronic-dosage format.

The EQUIGEN (Equivalence Among Antiepileptic Drug Generic and Brand Products in People With Epilepsy) Single Dose Study enrolled 48 epilepsy patients at any of six U.S. centers. All patients were on an antiepileptic drug other than lamotrigine, and the researchers randomized them to receive single doses of the brand-name reference form of lamotrigine (Lamictal), or either of two generic forms of lamotrigine. Patients received single dosages of each of the three study drugs with a 12-23 day washout period separating each dose (the preferred washout interval was 14 days), with the patients and researchers blinded to which specific product was administered at any time. The researchers selected the two FDA-approved generic products with the most widely divergent profiles based on in vitro dissolution testing and prior pharmacokinetic data supplied to the FDA. Forty-five patients received the scheduled two doses (on two different occasions) of each drug, a total of six test doses administered. The remaining three patients received a single dose of each of the three tested products.

All three products resulted in essentially superimposed concentration-time curves and area under the curve measures with no outliers or serious adverse events seen, Dr. Privitera and his associates reported in a poster presented at the meeting as well as during the session.