User login

University of Colorado: Annual Internal Medicine Program

When to think ‘primary aldosteronism’

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Primary aldosteronism, traditionally seen as a rare, stump-the-experts-type disorder, is now accepted as the cause of 5%-10% of all cases of what has been considered essential hypertension.

Primary aldosteronism is a readily treatable disorder, either surgically or medically, depending upon the subtype. So it’s essential to know which hypertensive patients to screen and how to confirm the diagnosis and then to move forward to identify the subtype in play, Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Primary aldosteronism occurs when the adrenal gland produces excessive aldosterone without being stimulated by renin. Aldosterone causes sodium retention in the kidney in exchange for potassium and hydrogen ions. The result is the triple harms of hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis, explained Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and clinical pharmacology and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

The two main subtypes of primary aldosteronism are idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA), also known as bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, which accounts for two-thirds of all cases, and unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, which accounts for the remaining third.

Which hypertensive patients should be screened for primary aldosteronism? Anyone with resistant hypertension as defined by inadequate blood pressure control while on three or more antihypertensive drugs; those with severe hypertension, meaning readings greater than 160/100 mm Hg; patients with onset of hypertension before age 20; and any hypertensive patient with hypokalemia, which can either be provoked by diuretic therapy or in some cases occurs spontaneously, the endocrinologist continued.

Screening for primary aldosteronism entails getting a morning blood sample to measure plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity after having the patient sit for 10 minutes. A positive screen requires both a plasma aldosterone level greater than 15 ng/dL and a plasma aldosterone/plasma renin activity ratio greater than 20.

“You can do this screening test in a patient on any medication except spironolactone. They have to stop that drug for at least 2 weeks first,” according to Dr. McDermott.

Confirmation of a positive screening test requires demonstration that the elevated aldosterone can’t be suppressed via volume expansion. This volume expansion can be accomplished in two ways: putting the patient on a high-salt diet for 3 days, which can generally be accomplished simply by eating some potato chips daily on top of a typically high-salt American diet, or by intravenous infusion of 2 L of normal saline over the course of 4 hours.

If a 24-hour urine collection on day 3 of a high-salt diet shows an aldosterone level in excess of 12 mcg, the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism is confirmed.

“If anyone in this room who doesn’t have primary aldosteronism had a high-salt diet for 3 days and we did a 24-hour urine on the third day, your aldosterone would be zero. So a level over 12 mcg is clearly abnormal,” Dr. McDermott emphasized.

Likewise, a plasma aldosterone greater than 10 ng/dL following the IV saline infusion is also confirmatory.

A good clinical clue that primary aldosteronism is due to an aldosterone-producing tumor is severe hypertension and/or severe hypokalemia in a patient under 40 years of age. A plasma aldosterone greater than 25 ng/dL or a urine aldosterone in excess of 30 mcg/24 hours is another useful clue because a tumor produces a lot more aldosterone than does bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.

If, and only if, a patient is willing to undergo surgery in the event further work-up establishes the presence of an aldosterone-producing tumor, the next step is an abdominal CT scan. If it reveals a unilateral hypodense nodule greater than 1 cm in size and the patient is less than 35 years old, referral for unilateral laparoscopic or open adrenalectomy is warranted. Preoperatively the patient should be placed on either spironolactone or eplerenone; these aldosterone antagonists block the effects of aldosterone on the kidney, with resultant normalization of hypertension and hypokalemia.

Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia is much more common than an aldosterone-producing tumor in patients older than age 35, so even when a unilateral nodule is found in such a patient it’s worthwhile to consider adrenal vein sampling. If the sampling lateralizes to one side then adrenalectomy can be offered. If there is no lateralization, however, the patient has IHA and medical management is appropriate. An aldosterone antagonist will normalize the hypokalemia but may not be sufficient to control the elevated blood pressure, in which case a calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, and/or angiotensin receptor blocker can be added.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Primary aldosteronism, traditionally seen as a rare, stump-the-experts-type disorder, is now accepted as the cause of 5%-10% of all cases of what has been considered essential hypertension.

Primary aldosteronism is a readily treatable disorder, either surgically or medically, depending upon the subtype. So it’s essential to know which hypertensive patients to screen and how to confirm the diagnosis and then to move forward to identify the subtype in play, Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Primary aldosteronism occurs when the adrenal gland produces excessive aldosterone without being stimulated by renin. Aldosterone causes sodium retention in the kidney in exchange for potassium and hydrogen ions. The result is the triple harms of hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis, explained Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and clinical pharmacology and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

The two main subtypes of primary aldosteronism are idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA), also known as bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, which accounts for two-thirds of all cases, and unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, which accounts for the remaining third.

Which hypertensive patients should be screened for primary aldosteronism? Anyone with resistant hypertension as defined by inadequate blood pressure control while on three or more antihypertensive drugs; those with severe hypertension, meaning readings greater than 160/100 mm Hg; patients with onset of hypertension before age 20; and any hypertensive patient with hypokalemia, which can either be provoked by diuretic therapy or in some cases occurs spontaneously, the endocrinologist continued.

Screening for primary aldosteronism entails getting a morning blood sample to measure plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity after having the patient sit for 10 minutes. A positive screen requires both a plasma aldosterone level greater than 15 ng/dL and a plasma aldosterone/plasma renin activity ratio greater than 20.

“You can do this screening test in a patient on any medication except spironolactone. They have to stop that drug for at least 2 weeks first,” according to Dr. McDermott.

Confirmation of a positive screening test requires demonstration that the elevated aldosterone can’t be suppressed via volume expansion. This volume expansion can be accomplished in two ways: putting the patient on a high-salt diet for 3 days, which can generally be accomplished simply by eating some potato chips daily on top of a typically high-salt American diet, or by intravenous infusion of 2 L of normal saline over the course of 4 hours.

If a 24-hour urine collection on day 3 of a high-salt diet shows an aldosterone level in excess of 12 mcg, the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism is confirmed.

“If anyone in this room who doesn’t have primary aldosteronism had a high-salt diet for 3 days and we did a 24-hour urine on the third day, your aldosterone would be zero. So a level over 12 mcg is clearly abnormal,” Dr. McDermott emphasized.

Likewise, a plasma aldosterone greater than 10 ng/dL following the IV saline infusion is also confirmatory.

A good clinical clue that primary aldosteronism is due to an aldosterone-producing tumor is severe hypertension and/or severe hypokalemia in a patient under 40 years of age. A plasma aldosterone greater than 25 ng/dL or a urine aldosterone in excess of 30 mcg/24 hours is another useful clue because a tumor produces a lot more aldosterone than does bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.

If, and only if, a patient is willing to undergo surgery in the event further work-up establishes the presence of an aldosterone-producing tumor, the next step is an abdominal CT scan. If it reveals a unilateral hypodense nodule greater than 1 cm in size and the patient is less than 35 years old, referral for unilateral laparoscopic or open adrenalectomy is warranted. Preoperatively the patient should be placed on either spironolactone or eplerenone; these aldosterone antagonists block the effects of aldosterone on the kidney, with resultant normalization of hypertension and hypokalemia.

Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia is much more common than an aldosterone-producing tumor in patients older than age 35, so even when a unilateral nodule is found in such a patient it’s worthwhile to consider adrenal vein sampling. If the sampling lateralizes to one side then adrenalectomy can be offered. If there is no lateralization, however, the patient has IHA and medical management is appropriate. An aldosterone antagonist will normalize the hypokalemia but may not be sufficient to control the elevated blood pressure, in which case a calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, and/or angiotensin receptor blocker can be added.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – Primary aldosteronism, traditionally seen as a rare, stump-the-experts-type disorder, is now accepted as the cause of 5%-10% of all cases of what has been considered essential hypertension.

Primary aldosteronism is a readily treatable disorder, either surgically or medically, depending upon the subtype. So it’s essential to know which hypertensive patients to screen and how to confirm the diagnosis and then to move forward to identify the subtype in play, Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Primary aldosteronism occurs when the adrenal gland produces excessive aldosterone without being stimulated by renin. Aldosterone causes sodium retention in the kidney in exchange for potassium and hydrogen ions. The result is the triple harms of hypertension, hypokalemia, and metabolic acidosis, explained Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and clinical pharmacology and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora.

The two main subtypes of primary aldosteronism are idiopathic hyperaldosteronism (IHA), also known as bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, which accounts for two-thirds of all cases, and unilateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, which accounts for the remaining third.

Which hypertensive patients should be screened for primary aldosteronism? Anyone with resistant hypertension as defined by inadequate blood pressure control while on three or more antihypertensive drugs; those with severe hypertension, meaning readings greater than 160/100 mm Hg; patients with onset of hypertension before age 20; and any hypertensive patient with hypokalemia, which can either be provoked by diuretic therapy or in some cases occurs spontaneously, the endocrinologist continued.

Screening for primary aldosteronism entails getting a morning blood sample to measure plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity after having the patient sit for 10 minutes. A positive screen requires both a plasma aldosterone level greater than 15 ng/dL and a plasma aldosterone/plasma renin activity ratio greater than 20.

“You can do this screening test in a patient on any medication except spironolactone. They have to stop that drug for at least 2 weeks first,” according to Dr. McDermott.

Confirmation of a positive screening test requires demonstration that the elevated aldosterone can’t be suppressed via volume expansion. This volume expansion can be accomplished in two ways: putting the patient on a high-salt diet for 3 days, which can generally be accomplished simply by eating some potato chips daily on top of a typically high-salt American diet, or by intravenous infusion of 2 L of normal saline over the course of 4 hours.

If a 24-hour urine collection on day 3 of a high-salt diet shows an aldosterone level in excess of 12 mcg, the diagnosis of primary aldosteronism is confirmed.

“If anyone in this room who doesn’t have primary aldosteronism had a high-salt diet for 3 days and we did a 24-hour urine on the third day, your aldosterone would be zero. So a level over 12 mcg is clearly abnormal,” Dr. McDermott emphasized.

Likewise, a plasma aldosterone greater than 10 ng/dL following the IV saline infusion is also confirmatory.

A good clinical clue that primary aldosteronism is due to an aldosterone-producing tumor is severe hypertension and/or severe hypokalemia in a patient under 40 years of age. A plasma aldosterone greater than 25 ng/dL or a urine aldosterone in excess of 30 mcg/24 hours is another useful clue because a tumor produces a lot more aldosterone than does bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.

If, and only if, a patient is willing to undergo surgery in the event further work-up establishes the presence of an aldosterone-producing tumor, the next step is an abdominal CT scan. If it reveals a unilateral hypodense nodule greater than 1 cm in size and the patient is less than 35 years old, referral for unilateral laparoscopic or open adrenalectomy is warranted. Preoperatively the patient should be placed on either spironolactone or eplerenone; these aldosterone antagonists block the effects of aldosterone on the kidney, with resultant normalization of hypertension and hypokalemia.

Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia is much more common than an aldosterone-producing tumor in patients older than age 35, so even when a unilateral nodule is found in such a patient it’s worthwhile to consider adrenal vein sampling. If the sampling lateralizes to one side then adrenalectomy can be offered. If there is no lateralization, however, the patient has IHA and medical management is appropriate. An aldosterone antagonist will normalize the hypokalemia but may not be sufficient to control the elevated blood pressure, in which case a calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, and/or angiotensin receptor blocker can be added.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts with regard to his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

Attack PCOS in adolescents hard

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The sweet spot for intervention in polycystic ovary syndrome occurs early: in the adolescent who doesn’t yet desire pregnancy and who is just starting to experience the classic PCOS progressive weight gain.

“The obstetricians don’t want to see these patients when they’re already 220 lb and they’re trying to induce ovulation. It’s our job to pick them up in their adolescence. You want to clamp the hormones – suppress the androgens – so that things will be better down the road,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman urged at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Aggressive treatment at this stage will reduce the risk of a host of potential health problems later. In addition to infertility issues, these include increased long-term risks of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, endometrial cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, noted Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine, ob.gyn., and physiology at the university and chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center.

PCOS is by far the most common cause of hyperandrogenic anovulation. Indeed, 6%-8% of all women in their childbearing years have PCOS. The condition is defined by clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and the presence of ovarian cysts or increased ovarian volume on ultrasound.

In the adolescent with PCOS who doesn’t desire pregnancy, Dr. Wierman takes a three-pronged treatment approach: regularize menses with a less androgenic oral contraceptive, such as one containing norethindrone, or by using cyclic progesterone; treat hirsutism with spironolactone at 50-100 mg once daily coupled with electrolysis for local control; and consider using short-acting metformin as an insulin-sensitizing agent.

The use of metformin in treating PCOS is controversial. It is off-label therapy. There have been no prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies supporting this application of the drug. Nevertheless, Dr. Wierman is a believer.

“If you take these adolescent girls, especially as they’re beginning to start the weight gain, and you give them metformin, it will stop the weight gain, improve their androgen level and their insulin resistance, and it will help them when they’re ready to have kids later on. I use metformin, and I call it Antabuse for fat: You cheat, you pay. You have no side effects if you eat healthy. If you eat fatty foods, you will have nausea and diarrhea,” she explained.

The endocrinologist added that she finds metformin works best in the adolescent with PCOS who has a family history of diabetes, is gaining weight, but is not yet diabetic herself.

“And that’s based on clinical experience, no prospective studies,” Dr. Wierman emphasized.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The sweet spot for intervention in polycystic ovary syndrome occurs early: in the adolescent who doesn’t yet desire pregnancy and who is just starting to experience the classic PCOS progressive weight gain.

“The obstetricians don’t want to see these patients when they’re already 220 lb and they’re trying to induce ovulation. It’s our job to pick them up in their adolescence. You want to clamp the hormones – suppress the androgens – so that things will be better down the road,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman urged at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Aggressive treatment at this stage will reduce the risk of a host of potential health problems later. In addition to infertility issues, these include increased long-term risks of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, endometrial cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, noted Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine, ob.gyn., and physiology at the university and chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center.

PCOS is by far the most common cause of hyperandrogenic anovulation. Indeed, 6%-8% of all women in their childbearing years have PCOS. The condition is defined by clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and the presence of ovarian cysts or increased ovarian volume on ultrasound.

In the adolescent with PCOS who doesn’t desire pregnancy, Dr. Wierman takes a three-pronged treatment approach: regularize menses with a less androgenic oral contraceptive, such as one containing norethindrone, or by using cyclic progesterone; treat hirsutism with spironolactone at 50-100 mg once daily coupled with electrolysis for local control; and consider using short-acting metformin as an insulin-sensitizing agent.

The use of metformin in treating PCOS is controversial. It is off-label therapy. There have been no prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies supporting this application of the drug. Nevertheless, Dr. Wierman is a believer.

“If you take these adolescent girls, especially as they’re beginning to start the weight gain, and you give them metformin, it will stop the weight gain, improve their androgen level and their insulin resistance, and it will help them when they’re ready to have kids later on. I use metformin, and I call it Antabuse for fat: You cheat, you pay. You have no side effects if you eat healthy. If you eat fatty foods, you will have nausea and diarrhea,” she explained.

The endocrinologist added that she finds metformin works best in the adolescent with PCOS who has a family history of diabetes, is gaining weight, but is not yet diabetic herself.

“And that’s based on clinical experience, no prospective studies,” Dr. Wierman emphasized.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The sweet spot for intervention in polycystic ovary syndrome occurs early: in the adolescent who doesn’t yet desire pregnancy and who is just starting to experience the classic PCOS progressive weight gain.

“The obstetricians don’t want to see these patients when they’re already 220 lb and they’re trying to induce ovulation. It’s our job to pick them up in their adolescence. You want to clamp the hormones – suppress the androgens – so that things will be better down the road,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman urged at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Aggressive treatment at this stage will reduce the risk of a host of potential health problems later. In addition to infertility issues, these include increased long-term risks of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, endometrial cancer, obstructive sleep apnea, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, noted Dr. Wierman, professor of medicine, ob.gyn., and physiology at the university and chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center.

PCOS is by far the most common cause of hyperandrogenic anovulation. Indeed, 6%-8% of all women in their childbearing years have PCOS. The condition is defined by clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism, oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and the presence of ovarian cysts or increased ovarian volume on ultrasound.

In the adolescent with PCOS who doesn’t desire pregnancy, Dr. Wierman takes a three-pronged treatment approach: regularize menses with a less androgenic oral contraceptive, such as one containing norethindrone, or by using cyclic progesterone; treat hirsutism with spironolactone at 50-100 mg once daily coupled with electrolysis for local control; and consider using short-acting metformin as an insulin-sensitizing agent.

The use of metformin in treating PCOS is controversial. It is off-label therapy. There have been no prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies supporting this application of the drug. Nevertheless, Dr. Wierman is a believer.

“If you take these adolescent girls, especially as they’re beginning to start the weight gain, and you give them metformin, it will stop the weight gain, improve their androgen level and their insulin resistance, and it will help them when they’re ready to have kids later on. I use metformin, and I call it Antabuse for fat: You cheat, you pay. You have no side effects if you eat healthy. If you eat fatty foods, you will have nausea and diarrhea,” she explained.

The endocrinologist added that she finds metformin works best in the adolescent with PCOS who has a family history of diabetes, is gaining weight, but is not yet diabetic herself.

“And that’s based on clinical experience, no prospective studies,” Dr. Wierman emphasized.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

New Treatment Target for Hypothyroid Elderly

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

New treatment target for hypothyroid elderly

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The latest major guidelines on management of hypothyroidism create a new, looser treatment target for older patients.

“This is a departure from the message we’ve given many times in the past. Elderly people seem to tolerate slight degrees of hypothyroidism and may actually benefit from it,” Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The American Thyroid Association guidelines issued late last year (Thyroid. 2014 Dec;24[12]:1670-75) raise the target serum TSH to 4-6 mIU/L in hypothyroid individuals age 70 or older. The target serum TSH in nonelderly, nonpregnant patients remains unchanged at 0.5-4.5 mIU/L, noted Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes practice at the University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora.

“The slightly higher TSH treatment target in elderly patients is very heavily evidence-based. Studies showed that people over age 70 often did worse if their TSH was maintained in the low end of the normal range, and that people whose TSH was maintained up to about 6 mIU/L didn’t seem to have any adverse effects from that. It’s kind of a moving target: we’ll probably see the data reevaluated over time. But I think it’s clear that normal elderly people have a normal TSH that’s slightly higher,” according to the endocrinologist.

The starting dose of levothyroxine (LT4) in older patients is 25-50 mcg/day. The TSH level should be rechecked after 6 weeks in patients with overt hypothyroidism and 6-10 weeks in those with subclinical hypothyroidism, with LT4 then being titrated in the elderly until it’s in the 4-6 mIU/L range.

Speaking of subclinical hypothyroidism, which is defined by an elevated TSH but a normal free T4 level, four studies now show the same thing: While subclinical hypothyroidism is independently associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in patients under age 65, it does not carry any increased cardiovascular mortality risk in older individuals. The first of these studies, a meta-analysis of 15 clinical trials totalling 2,531 subclinically hypothyroid patients and more than 26,000 controls, found a 37% increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients younger than 65 with subclinical hypothyroidism, but no increase in older people with the disorder (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Aug;93[8]:2998-3007).

“We don’t know why that is, but it’s the reason the recommended TSH range when treating people for subclinical or overt hypothyroidism has now changed in people over age 70,” Dr. McDermott explained.

The consensus recommendations of the American Thyroid Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists advise treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism involving a TSH level greater than 10.0 mIU/L. In patients with lesser elevations of TSH, however, clinical judgment is critical in deciding whether to treat or monitor.

“If the person has symptoms, treatment is very reasonable. You should know, however, that one-third of people who have a TSH of 4.5-10.0 mIU/L will have a normal TSH 1 year later if you don’t treat them. So if they’re not symptomatic you may usually monitor these patients,” he said.

While LT4 remains the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism, 16% of patients have persistent symptoms despite optimal LT4 therapy. They appear to benefit from a combination of LT4 and liothyronine (LT3) given in a 10:1 ratio. Because LT3 lasts for only about 8 hours, it’s best administered twice daily. Thyroid tests should be obtained before the medication is taken because triiodothyronine (T3) levels rise abruptly in response to a dose.

Dr. McDermott reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

Testosterone regimen may affect cardiovascular risk

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The delivery route of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism has emerged as a new issue in the still-developing story of the therapy’s cardiovascular safety.

A retrospective cohort study of more than 544,000 men in the United States and England who initiated testosterone therapy concluded that the associated cardiovascular risk varied significantly with the dosage form prescribed.

Testosterone by injection inevitably results in pharmacologic hormone levels. Study participants who initiated testosterone injections had a significant 26% increase in the 1-year risk of the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or stroke, compared with men using testosterone gels, which generally achieve physiologic levels. The testosterone injectors also had a 34% increase in 1-year all-cause mortality and a 16% increase in all-cause hospitalizations.

In all, 27% of the men received testosterone injections, 56% gels, and 7% patches. Outcomes did not differ between men on the gels and those on testosterone patches (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Jul 1;175[7]:1187-96).

“This study has made our VA hospital – and VAs across the country – relook at what they’re covering as far as testosterone therapy,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wierman, who wrote the editorial accompanying the JAMA study, acknowledged the inherent limitations of an epidemiologic study such as this, which can’t prove cause-and-effect. Nonetheless, the study’s strengths, including its sheer size, make it deserving of attention. And the findings raise legitimate concerns about the huge increase in testosterone prescribing in recent years in the U.S. and elsewhere, said Dr. Wierman, who is chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center and professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at the university (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175[7]:1197-8).

Those concerns were brought to the fore in what she termed an “alarming” Food and Drug Administration report issued last year. The FDA determined that during 2010-2013, testosterone prescriptions in the U.S. jumped by 76% to 2.3 million annually. Disturbingly, hypogonadism was documented in only 50% of patient charts. One quarter of the men didn’t have a baseline testosterone measurement, and 21% never had a follow-up level checked after going on the hormone therapy.

“It shows there’s a lot of charlatanism out there, and a lot of abuse,” she commented.

The FDA also found that 57% of men being prescribed testosterone were also prescribed cardiac medications, suggesting they are at increased cardiovascular risk. Yet the cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy remains an open question, with all eyes now on the 800-subject, randomized, placebo-controlled, National Institute on Aging–sponsored Testosterone Trial in Older Men, due to report results next year.

In the interim, Dr. Wierman’s take-home message on testosterone, based on her decades of work in the field, is simple: Too little is bad; it is manifest in a variety of physical, psychologic, and sexual symptoms, many of which are related to aging and aren’t sensitive or specific to hypogonadism. Too much is bad as well, posing potential risks of accelerated growth of undiagnosed prostate cancer, tissue edema in patients with cardiac, liver, or renal disease, gynecomastia, erythrocytosis, sleep apnea, stimulation of platelet aggregation, and possibly an increase in cardiovascular events.

The virtues of the middle path were recently underscored in a study of 3,690 community-dwelling Australian men ages 70-89. Over the course of up to 9 years of follow-up, death rates were lower in men in the middle quartiles for testosterone than in those with low or high levels (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jan;99[1]:E9-18).

“This suggests that there may be side effects of pushing testosterone up above the physiologic range, at least in some sets of men,” according to Dr. Wierman.

She fully supports the Endocrine Society’s recommendations to treat men with both signs and symptoms of hypogonadism and documented low testosterone due to a known disorder, and to target physiologic testosterone levels.

“Usually you can find out what the cause is. I want to be a hormone detective. I want to find out what the cause is because if I can reverse the cause, I’d rather have the testosterone level come up on its own,” the endocrinologist said.

Of course, the cause isn’t always reversible. For example, high-dose narcotic therapy is one of the most common causes of acquired central hypogonadism in VA hospitals.

“There are a lot of wounded young men coming back from the war who have horrible osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome who are on narcotics and can’t get off them, and who are not getting testosterone and should be on it,” she said.

There has been a major change in thinking with regard to late-onset hypogonadism, also known as andropause, a disorder that has served as the rationale for much testosterone prescribing. Fifteen years, ago based on data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging, it was thought that up to 30% of older men have andropause; however, that conclusion was based solely on testosterone levels, with no consideration of signs and symptoms.

More recently, European investigators used an appropriately more rigorous definition of andropause: that is, a serum total testosterone level below 320 ng/mL plus at least three sexual symptoms, such as low sexual desire, poor morning erection, and erectile dysfunction. By this definition, the prevalence of andropause is much lower, a maximum of 3%-5%. And it’s influenced by advancing age, body mass index, and comorbid conditions (N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 8;363[2]:123-35).

“The 30% prevalence figure that’s out there is just wrong,” Dr. Wierman stressed. “There may be a diagnosis of late-onset hypogonadism – it’s a diagnosis of exclusion – but it’s much lower.”

In a follow-up study, the same European researchers showed that weight loss in middle-aged and older men was associated with a proportional increase in serum testosterone and sex-hormone binding globulin, while weight gain brought a proportional drop in testosterone and SHBG (Eur J Endocrinol. 2013 Feb 20;168[3]:445-55).

Dr. Wierman said this study contains an important lesson for everyday clinical practice: In overweight older men with low-normal testosterone levels in the 200-250 ng/mL range, the primary recommendation should be diet and lifestyle modification aimed at achieving weight loss, not testosterone therapy. Successful weight loss will boost their testosterone level, improve comorbid obstructive sleep apnea, enhance their cardiovascular and metabolic fitness, and in some cases improve erectile dysfunction, although she was quick to add that low testosterone is “actually a pretty modest cause” of erectile dysfunction.

The number-one cause of erectile dysfunction is poor vascular plumbing as predicted by hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Neurogenic causes are number two and are predicted by chronic back injury, diabetes, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Hormonal causes are next, followed by performance anxiety and other psychogenic issues, and lastly iatrogenic causes involving medication side effects.

Dr. Wierman reported that she is coprincipal investigator for a clinical trial on neuroendocrine dysfunction during rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury funded by the Colorado Brain Trust. Abbvie donates the testosterone gel and placebo utilized in the study.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The delivery route of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism has emerged as a new issue in the still-developing story of the therapy’s cardiovascular safety.

A retrospective cohort study of more than 544,000 men in the United States and England who initiated testosterone therapy concluded that the associated cardiovascular risk varied significantly with the dosage form prescribed.

Testosterone by injection inevitably results in pharmacologic hormone levels. Study participants who initiated testosterone injections had a significant 26% increase in the 1-year risk of the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or stroke, compared with men using testosterone gels, which generally achieve physiologic levels. The testosterone injectors also had a 34% increase in 1-year all-cause mortality and a 16% increase in all-cause hospitalizations.

In all, 27% of the men received testosterone injections, 56% gels, and 7% patches. Outcomes did not differ between men on the gels and those on testosterone patches (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Jul 1;175[7]:1187-96).

“This study has made our VA hospital – and VAs across the country – relook at what they’re covering as far as testosterone therapy,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wierman, who wrote the editorial accompanying the JAMA study, acknowledged the inherent limitations of an epidemiologic study such as this, which can’t prove cause-and-effect. Nonetheless, the study’s strengths, including its sheer size, make it deserving of attention. And the findings raise legitimate concerns about the huge increase in testosterone prescribing in recent years in the U.S. and elsewhere, said Dr. Wierman, who is chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center and professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at the university (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175[7]:1197-8).

Those concerns were brought to the fore in what she termed an “alarming” Food and Drug Administration report issued last year. The FDA determined that during 2010-2013, testosterone prescriptions in the U.S. jumped by 76% to 2.3 million annually. Disturbingly, hypogonadism was documented in only 50% of patient charts. One quarter of the men didn’t have a baseline testosterone measurement, and 21% never had a follow-up level checked after going on the hormone therapy.

“It shows there’s a lot of charlatanism out there, and a lot of abuse,” she commented.

The FDA also found that 57% of men being prescribed testosterone were also prescribed cardiac medications, suggesting they are at increased cardiovascular risk. Yet the cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy remains an open question, with all eyes now on the 800-subject, randomized, placebo-controlled, National Institute on Aging–sponsored Testosterone Trial in Older Men, due to report results next year.

In the interim, Dr. Wierman’s take-home message on testosterone, based on her decades of work in the field, is simple: Too little is bad; it is manifest in a variety of physical, psychologic, and sexual symptoms, many of which are related to aging and aren’t sensitive or specific to hypogonadism. Too much is bad as well, posing potential risks of accelerated growth of undiagnosed prostate cancer, tissue edema in patients with cardiac, liver, or renal disease, gynecomastia, erythrocytosis, sleep apnea, stimulation of platelet aggregation, and possibly an increase in cardiovascular events.

The virtues of the middle path were recently underscored in a study of 3,690 community-dwelling Australian men ages 70-89. Over the course of up to 9 years of follow-up, death rates were lower in men in the middle quartiles for testosterone than in those with low or high levels (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jan;99[1]:E9-18).

“This suggests that there may be side effects of pushing testosterone up above the physiologic range, at least in some sets of men,” according to Dr. Wierman.

She fully supports the Endocrine Society’s recommendations to treat men with both signs and symptoms of hypogonadism and documented low testosterone due to a known disorder, and to target physiologic testosterone levels.

“Usually you can find out what the cause is. I want to be a hormone detective. I want to find out what the cause is because if I can reverse the cause, I’d rather have the testosterone level come up on its own,” the endocrinologist said.

Of course, the cause isn’t always reversible. For example, high-dose narcotic therapy is one of the most common causes of acquired central hypogonadism in VA hospitals.

“There are a lot of wounded young men coming back from the war who have horrible osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome who are on narcotics and can’t get off them, and who are not getting testosterone and should be on it,” she said.

There has been a major change in thinking with regard to late-onset hypogonadism, also known as andropause, a disorder that has served as the rationale for much testosterone prescribing. Fifteen years, ago based on data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging, it was thought that up to 30% of older men have andropause; however, that conclusion was based solely on testosterone levels, with no consideration of signs and symptoms.

More recently, European investigators used an appropriately more rigorous definition of andropause: that is, a serum total testosterone level below 320 ng/mL plus at least three sexual symptoms, such as low sexual desire, poor morning erection, and erectile dysfunction. By this definition, the prevalence of andropause is much lower, a maximum of 3%-5%. And it’s influenced by advancing age, body mass index, and comorbid conditions (N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 8;363[2]:123-35).

“The 30% prevalence figure that’s out there is just wrong,” Dr. Wierman stressed. “There may be a diagnosis of late-onset hypogonadism – it’s a diagnosis of exclusion – but it’s much lower.”

In a follow-up study, the same European researchers showed that weight loss in middle-aged and older men was associated with a proportional increase in serum testosterone and sex-hormone binding globulin, while weight gain brought a proportional drop in testosterone and SHBG (Eur J Endocrinol. 2013 Feb 20;168[3]:445-55).

Dr. Wierman said this study contains an important lesson for everyday clinical practice: In overweight older men with low-normal testosterone levels in the 200-250 ng/mL range, the primary recommendation should be diet and lifestyle modification aimed at achieving weight loss, not testosterone therapy. Successful weight loss will boost their testosterone level, improve comorbid obstructive sleep apnea, enhance their cardiovascular and metabolic fitness, and in some cases improve erectile dysfunction, although she was quick to add that low testosterone is “actually a pretty modest cause” of erectile dysfunction.

The number-one cause of erectile dysfunction is poor vascular plumbing as predicted by hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Neurogenic causes are number two and are predicted by chronic back injury, diabetes, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Hormonal causes are next, followed by performance anxiety and other psychogenic issues, and lastly iatrogenic causes involving medication side effects.

Dr. Wierman reported that she is coprincipal investigator for a clinical trial on neuroendocrine dysfunction during rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury funded by the Colorado Brain Trust. Abbvie donates the testosterone gel and placebo utilized in the study.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The delivery route of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism has emerged as a new issue in the still-developing story of the therapy’s cardiovascular safety.

A retrospective cohort study of more than 544,000 men in the United States and England who initiated testosterone therapy concluded that the associated cardiovascular risk varied significantly with the dosage form prescribed.

Testosterone by injection inevitably results in pharmacologic hormone levels. Study participants who initiated testosterone injections had a significant 26% increase in the 1-year risk of the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or stroke, compared with men using testosterone gels, which generally achieve physiologic levels. The testosterone injectors also had a 34% increase in 1-year all-cause mortality and a 16% increase in all-cause hospitalizations.

In all, 27% of the men received testosterone injections, 56% gels, and 7% patches. Outcomes did not differ between men on the gels and those on testosterone patches (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Jul 1;175[7]:1187-96).

“This study has made our VA hospital – and VAs across the country – relook at what they’re covering as far as testosterone therapy,” Dr. Margaret E. Wierman said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wierman, who wrote the editorial accompanying the JAMA study, acknowledged the inherent limitations of an epidemiologic study such as this, which can’t prove cause-and-effect. Nonetheless, the study’s strengths, including its sheer size, make it deserving of attention. And the findings raise legitimate concerns about the huge increase in testosterone prescribing in recent years in the U.S. and elsewhere, said Dr. Wierman, who is chief of endocrinology at the Denver VA Medical Center and professor of medicine, physiology and biophysics at the university (JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175[7]:1197-8).

Those concerns were brought to the fore in what she termed an “alarming” Food and Drug Administration report issued last year. The FDA determined that during 2010-2013, testosterone prescriptions in the U.S. jumped by 76% to 2.3 million annually. Disturbingly, hypogonadism was documented in only 50% of patient charts. One quarter of the men didn’t have a baseline testosterone measurement, and 21% never had a follow-up level checked after going on the hormone therapy.

“It shows there’s a lot of charlatanism out there, and a lot of abuse,” she commented.

The FDA also found that 57% of men being prescribed testosterone were also prescribed cardiac medications, suggesting they are at increased cardiovascular risk. Yet the cardiovascular safety of testosterone therapy remains an open question, with all eyes now on the 800-subject, randomized, placebo-controlled, National Institute on Aging–sponsored Testosterone Trial in Older Men, due to report results next year.

In the interim, Dr. Wierman’s take-home message on testosterone, based on her decades of work in the field, is simple: Too little is bad; it is manifest in a variety of physical, psychologic, and sexual symptoms, many of which are related to aging and aren’t sensitive or specific to hypogonadism. Too much is bad as well, posing potential risks of accelerated growth of undiagnosed prostate cancer, tissue edema in patients with cardiac, liver, or renal disease, gynecomastia, erythrocytosis, sleep apnea, stimulation of platelet aggregation, and possibly an increase in cardiovascular events.

The virtues of the middle path were recently underscored in a study of 3,690 community-dwelling Australian men ages 70-89. Over the course of up to 9 years of follow-up, death rates were lower in men in the middle quartiles for testosterone than in those with low or high levels (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jan;99[1]:E9-18).

“This suggests that there may be side effects of pushing testosterone up above the physiologic range, at least in some sets of men,” according to Dr. Wierman.

She fully supports the Endocrine Society’s recommendations to treat men with both signs and symptoms of hypogonadism and documented low testosterone due to a known disorder, and to target physiologic testosterone levels.

“Usually you can find out what the cause is. I want to be a hormone detective. I want to find out what the cause is because if I can reverse the cause, I’d rather have the testosterone level come up on its own,” the endocrinologist said.

Of course, the cause isn’t always reversible. For example, high-dose narcotic therapy is one of the most common causes of acquired central hypogonadism in VA hospitals.

“There are a lot of wounded young men coming back from the war who have horrible osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome who are on narcotics and can’t get off them, and who are not getting testosterone and should be on it,” she said.

There has been a major change in thinking with regard to late-onset hypogonadism, also known as andropause, a disorder that has served as the rationale for much testosterone prescribing. Fifteen years, ago based on data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging, it was thought that up to 30% of older men have andropause; however, that conclusion was based solely on testosterone levels, with no consideration of signs and symptoms.

More recently, European investigators used an appropriately more rigorous definition of andropause: that is, a serum total testosterone level below 320 ng/mL plus at least three sexual symptoms, such as low sexual desire, poor morning erection, and erectile dysfunction. By this definition, the prevalence of andropause is much lower, a maximum of 3%-5%. And it’s influenced by advancing age, body mass index, and comorbid conditions (N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 8;363[2]:123-35).

“The 30% prevalence figure that’s out there is just wrong,” Dr. Wierman stressed. “There may be a diagnosis of late-onset hypogonadism – it’s a diagnosis of exclusion – but it’s much lower.”

In a follow-up study, the same European researchers showed that weight loss in middle-aged and older men was associated with a proportional increase in serum testosterone and sex-hormone binding globulin, while weight gain brought a proportional drop in testosterone and SHBG (Eur J Endocrinol. 2013 Feb 20;168[3]:445-55).

Dr. Wierman said this study contains an important lesson for everyday clinical practice: In overweight older men with low-normal testosterone levels in the 200-250 ng/mL range, the primary recommendation should be diet and lifestyle modification aimed at achieving weight loss, not testosterone therapy. Successful weight loss will boost their testosterone level, improve comorbid obstructive sleep apnea, enhance their cardiovascular and metabolic fitness, and in some cases improve erectile dysfunction, although she was quick to add that low testosterone is “actually a pretty modest cause” of erectile dysfunction.

The number-one cause of erectile dysfunction is poor vascular plumbing as predicted by hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Neurogenic causes are number two and are predicted by chronic back injury, diabetes, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Hormonal causes are next, followed by performance anxiety and other psychogenic issues, and lastly iatrogenic causes involving medication side effects.

Dr. Wierman reported that she is coprincipal investigator for a clinical trial on neuroendocrine dysfunction during rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury funded by the Colorado Brain Trust. Abbvie donates the testosterone gel and placebo utilized in the study.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

New shingles vaccine delivers whopping efficacy

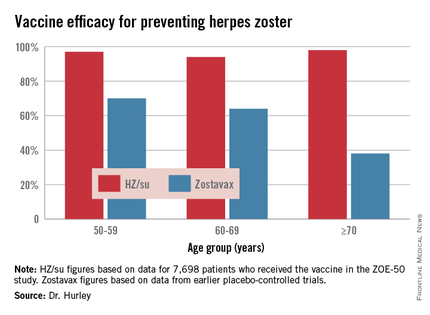

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The investigational HZ/su vaccine looks like it could be the herpes zoster vaccine of the future for older adults, Dr. Laura P. Hurley said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The vaccine demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in the recently reported international ZOE-50 study, which featured 15,411 participants aged 50 years and older who were randomized to either vaccine or placebo.

During a mean 3.2 years of follow-up, the vaccine efficacy was 97.2% for prevention of herpes zoster in adults aged 50 and older. Herpes zoster occurred in 6 subjects in the vaccine group and 210 in the placebo arm. That’s an incidence rate of 0.3 versus 9.1 cases per 1,000 person-years (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 28;372[22]:2087-96).

The HZ/su vaccine, a subunit vaccine containing varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E and a proprietary adjuvant system, crushed the current Zostavax vaccine in terms of vaccine efficacy in all older-age subgroups based upon comparative data from the earlier large placebo-controlled trials of Zostavax. Efficacy of the HZ/su vaccine was independent of age and was as good in persons over age 70 – the age group where the incidence of herpes zoster and its complications is highest – as in the 50- to 59-year-olds, noted Dr. Hurley, a general internist and vaccination researcher at the university.

Follow-up in ZOE-50 is ongoing and planned for at least 10 years in order to determine the duration of protection. Thus far, however, there is no signal of waning efficacy. In contrast, a recent study of nearly 7,000 Zostavax recipients showed that its efficacy declined over time and remained statistically significant only through year 8 post vaccination (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar 15;60[6]:900-9), she observed.

Dr. Hurley described another big advantage of the investigational vaccine, in addition to its almost-too-good-to-be-true efficacy: the fact that, unlike Zostavax, it’s not a live-virus vaccine. That means it doesn’t require freezer storage, thereby removing a major impediment to convenient vaccination. It also means it can potentially be safe for use in immunocompromised patients. Such patients were excluded from ZOE-50 but are the focus of ongoing studies conducted in patients with hematologic and solid organ malignancies, as well as renal transplant recipients.

The HZ/su vaccine has two major drawbacks. One is that it’s delivered in a series of two intramuscular doses with the injections given 2 months apart. “A two-shot series always creates problems with implementation,” according to Dr. Hurley.

The other shortcoming is the high rate of local and systemic reactions during the first week post vaccination. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity and lasted only 1 or 2 days.

“Patients who had a large local reaction to the first shot and were asked to come back 2 months later for the second might be less inclined to do so,” the physician said.

The HZ/su vaccine is being developed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Hurley reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

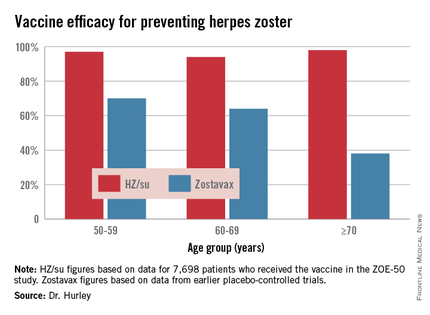

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The investigational HZ/su vaccine looks like it could be the herpes zoster vaccine of the future for older adults, Dr. Laura P. Hurley said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The vaccine demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in the recently reported international ZOE-50 study, which featured 15,411 participants aged 50 years and older who were randomized to either vaccine or placebo.

During a mean 3.2 years of follow-up, the vaccine efficacy was 97.2% for prevention of herpes zoster in adults aged 50 and older. Herpes zoster occurred in 6 subjects in the vaccine group and 210 in the placebo arm. That’s an incidence rate of 0.3 versus 9.1 cases per 1,000 person-years (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 28;372[22]:2087-96).

The HZ/su vaccine, a subunit vaccine containing varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E and a proprietary adjuvant system, crushed the current Zostavax vaccine in terms of vaccine efficacy in all older-age subgroups based upon comparative data from the earlier large placebo-controlled trials of Zostavax. Efficacy of the HZ/su vaccine was independent of age and was as good in persons over age 70 – the age group where the incidence of herpes zoster and its complications is highest – as in the 50- to 59-year-olds, noted Dr. Hurley, a general internist and vaccination researcher at the university.

Follow-up in ZOE-50 is ongoing and planned for at least 10 years in order to determine the duration of protection. Thus far, however, there is no signal of waning efficacy. In contrast, a recent study of nearly 7,000 Zostavax recipients showed that its efficacy declined over time and remained statistically significant only through year 8 post vaccination (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar 15;60[6]:900-9), she observed.

Dr. Hurley described another big advantage of the investigational vaccine, in addition to its almost-too-good-to-be-true efficacy: the fact that, unlike Zostavax, it’s not a live-virus vaccine. That means it doesn’t require freezer storage, thereby removing a major impediment to convenient vaccination. It also means it can potentially be safe for use in immunocompromised patients. Such patients were excluded from ZOE-50 but are the focus of ongoing studies conducted in patients with hematologic and solid organ malignancies, as well as renal transplant recipients.

The HZ/su vaccine has two major drawbacks. One is that it’s delivered in a series of two intramuscular doses with the injections given 2 months apart. “A two-shot series always creates problems with implementation,” according to Dr. Hurley.

The other shortcoming is the high rate of local and systemic reactions during the first week post vaccination. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity and lasted only 1 or 2 days.

“Patients who had a large local reaction to the first shot and were asked to come back 2 months later for the second might be less inclined to do so,” the physician said.

The HZ/su vaccine is being developed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Hurley reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

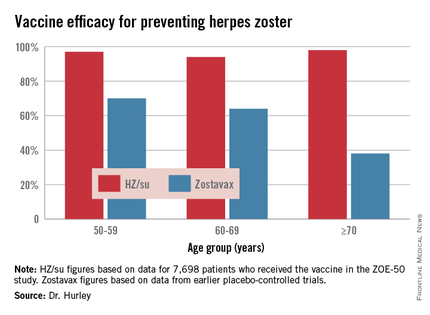

ESTES PARK, COLO. – The investigational HZ/su vaccine looks like it could be the herpes zoster vaccine of the future for older adults, Dr. Laura P. Hurley said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

The vaccine demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in the recently reported international ZOE-50 study, which featured 15,411 participants aged 50 years and older who were randomized to either vaccine or placebo.

During a mean 3.2 years of follow-up, the vaccine efficacy was 97.2% for prevention of herpes zoster in adults aged 50 and older. Herpes zoster occurred in 6 subjects in the vaccine group and 210 in the placebo arm. That’s an incidence rate of 0.3 versus 9.1 cases per 1,000 person-years (N Engl J Med. 2015 May 28;372[22]:2087-96).

The HZ/su vaccine, a subunit vaccine containing varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E and a proprietary adjuvant system, crushed the current Zostavax vaccine in terms of vaccine efficacy in all older-age subgroups based upon comparative data from the earlier large placebo-controlled trials of Zostavax. Efficacy of the HZ/su vaccine was independent of age and was as good in persons over age 70 – the age group where the incidence of herpes zoster and its complications is highest – as in the 50- to 59-year-olds, noted Dr. Hurley, a general internist and vaccination researcher at the university.

Follow-up in ZOE-50 is ongoing and planned for at least 10 years in order to determine the duration of protection. Thus far, however, there is no signal of waning efficacy. In contrast, a recent study of nearly 7,000 Zostavax recipients showed that its efficacy declined over time and remained statistically significant only through year 8 post vaccination (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Mar 15;60[6]:900-9), she observed.

Dr. Hurley described another big advantage of the investigational vaccine, in addition to its almost-too-good-to-be-true efficacy: the fact that, unlike Zostavax, it’s not a live-virus vaccine. That means it doesn’t require freezer storage, thereby removing a major impediment to convenient vaccination. It also means it can potentially be safe for use in immunocompromised patients. Such patients were excluded from ZOE-50 but are the focus of ongoing studies conducted in patients with hematologic and solid organ malignancies, as well as renal transplant recipients.

The HZ/su vaccine has two major drawbacks. One is that it’s delivered in a series of two intramuscular doses with the injections given 2 months apart. “A two-shot series always creates problems with implementation,” according to Dr. Hurley.

The other shortcoming is the high rate of local and systemic reactions during the first week post vaccination. Most of the reactions were mild to moderate in severity and lasted only 1 or 2 days.

“Patients who had a large local reaction to the first shot and were asked to come back 2 months later for the second might be less inclined to do so,” the physician said.

The HZ/su vaccine is being developed by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Hurley reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

Nocturnal Back Pain Suggests Systemic Disorder