User login

Dual SGLT1-2 inhibitor improved glycemic control in T1DM

SAN DIEGO – levels to less than 7% without severe diabetic ketoacidosis or hypoglycemia, compared with placebo, in a pivotal phase III trial of adults with type 1 diabetes.

After 24 weeks, 58 (22%) of patients on placebo achieved this combined endpoint, compared with 44% of patients who received 400 mg oral daily sotagliflozin (P less than .001) and 34% of those who received 200 mg (P = .002), John B. Buse, MD, PhD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Sotagliflozin significantly reduced hemoglobin A1c in the setting of optimized insulin therapy, with a safety profile that supports further clinical development,” said Dr. Buse, lead investigator of the Tandem1 trial.

To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive sotagliflozin for type 1 diabetes, Dr. Buse and his associates randomly assigned 793 patients from 75 North American sites to receive either placebo or treatment at 200 mg or 400 mg for 24 weeks. Patients and investigators were blinded as to treatment arm. Patients received optimized insulin, and the trial arms were demographically and clinically similar at baseline. The average age was 46 years, mean body mass index was 30 kg per m2, average daily insulin dose was 0.73 U per kg, and mean baseline HbA1c was 7.58 % (standard deviation, 0.73%).

By week 24, HbA1c levels fell by an average of 8% on placebo, 43% on 200 mg sotagliflozin, and 49% on 400 mg sotagliflozin, Dr. Buse reported. “The decrease from baseline was highly significant at both doses of sotagliflozin, compared with placebo,” he noted. Adjunctive sotagliflozin therapy also led to significant reductions in bolus insulin doses, fasting blood glucose levels, and body weight as compared with placebo. Drops in body weight averaged 1.6 kg at 200 mg and 2.7 kg at 400 mg, while placebo patients gained an average of 0.8 kg.

There were no deaths during the trial. Rates of treatment-associated adverse events were similar across groups, and serious adverse events affected 3% of placebo patients, 4% of 200-mg patients, and 7% of 400-mg patients. In all, 7% of placebo recipients experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 4%-5% of patients on sotagliflozin. The incidence of DKA was 0% on placebo and 1%-3% on sotagliflozin, with a higher rate among patients on pumps, Dr. Buse noted. Most cases of DKA were considered mildly to moderately severe, with blood glucose levels under 250 mg per dL, he added. Sotagliflozin also was associated with dose-dependent increases in rates of diarrhea and genital mycotic infections, which reached about 10% in the 400-mg arm. However, less than 1% of patients stopped treatment because of either adverse event.

“This is the first report of a successful phase III trial of an oral antidiabetic as an adjunct to insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Buse commented. Sotagliflozin met all prespecified endpoints in the trial, and the 400-mg dose significantly outperformed placebo on each endpoint, he added. A second phase III trial of sotagliflozin (inTandem2) is ongoing, and investigators plan to present pooled data from both trials later this year. Meanwhile, a third phase III trial (inTandem3) is comparing 400 mg sotagliflozin or placebo for patients receiving any type of insulin therapy.

Lexicon Pharmaceuticals developed sotagliflozin and funded the study. Dr. Buse disclosed research funding from Lexicon, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – levels to less than 7% without severe diabetic ketoacidosis or hypoglycemia, compared with placebo, in a pivotal phase III trial of adults with type 1 diabetes.

After 24 weeks, 58 (22%) of patients on placebo achieved this combined endpoint, compared with 44% of patients who received 400 mg oral daily sotagliflozin (P less than .001) and 34% of those who received 200 mg (P = .002), John B. Buse, MD, PhD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Sotagliflozin significantly reduced hemoglobin A1c in the setting of optimized insulin therapy, with a safety profile that supports further clinical development,” said Dr. Buse, lead investigator of the Tandem1 trial.

To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive sotagliflozin for type 1 diabetes, Dr. Buse and his associates randomly assigned 793 patients from 75 North American sites to receive either placebo or treatment at 200 mg or 400 mg for 24 weeks. Patients and investigators were blinded as to treatment arm. Patients received optimized insulin, and the trial arms were demographically and clinically similar at baseline. The average age was 46 years, mean body mass index was 30 kg per m2, average daily insulin dose was 0.73 U per kg, and mean baseline HbA1c was 7.58 % (standard deviation, 0.73%).

By week 24, HbA1c levels fell by an average of 8% on placebo, 43% on 200 mg sotagliflozin, and 49% on 400 mg sotagliflozin, Dr. Buse reported. “The decrease from baseline was highly significant at both doses of sotagliflozin, compared with placebo,” he noted. Adjunctive sotagliflozin therapy also led to significant reductions in bolus insulin doses, fasting blood glucose levels, and body weight as compared with placebo. Drops in body weight averaged 1.6 kg at 200 mg and 2.7 kg at 400 mg, while placebo patients gained an average of 0.8 kg.

There were no deaths during the trial. Rates of treatment-associated adverse events were similar across groups, and serious adverse events affected 3% of placebo patients, 4% of 200-mg patients, and 7% of 400-mg patients. In all, 7% of placebo recipients experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 4%-5% of patients on sotagliflozin. The incidence of DKA was 0% on placebo and 1%-3% on sotagliflozin, with a higher rate among patients on pumps, Dr. Buse noted. Most cases of DKA were considered mildly to moderately severe, with blood glucose levels under 250 mg per dL, he added. Sotagliflozin also was associated with dose-dependent increases in rates of diarrhea and genital mycotic infections, which reached about 10% in the 400-mg arm. However, less than 1% of patients stopped treatment because of either adverse event.

“This is the first report of a successful phase III trial of an oral antidiabetic as an adjunct to insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Buse commented. Sotagliflozin met all prespecified endpoints in the trial, and the 400-mg dose significantly outperformed placebo on each endpoint, he added. A second phase III trial of sotagliflozin (inTandem2) is ongoing, and investigators plan to present pooled data from both trials later this year. Meanwhile, a third phase III trial (inTandem3) is comparing 400 mg sotagliflozin or placebo for patients receiving any type of insulin therapy.

Lexicon Pharmaceuticals developed sotagliflozin and funded the study. Dr. Buse disclosed research funding from Lexicon, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – levels to less than 7% without severe diabetic ketoacidosis or hypoglycemia, compared with placebo, in a pivotal phase III trial of adults with type 1 diabetes.

After 24 weeks, 58 (22%) of patients on placebo achieved this combined endpoint, compared with 44% of patients who received 400 mg oral daily sotagliflozin (P less than .001) and 34% of those who received 200 mg (P = .002), John B. Buse, MD, PhD, reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “Sotagliflozin significantly reduced hemoglobin A1c in the setting of optimized insulin therapy, with a safety profile that supports further clinical development,” said Dr. Buse, lead investigator of the Tandem1 trial.

To further evaluate the efficacy and safety of adjunctive sotagliflozin for type 1 diabetes, Dr. Buse and his associates randomly assigned 793 patients from 75 North American sites to receive either placebo or treatment at 200 mg or 400 mg for 24 weeks. Patients and investigators were blinded as to treatment arm. Patients received optimized insulin, and the trial arms were demographically and clinically similar at baseline. The average age was 46 years, mean body mass index was 30 kg per m2, average daily insulin dose was 0.73 U per kg, and mean baseline HbA1c was 7.58 % (standard deviation, 0.73%).

By week 24, HbA1c levels fell by an average of 8% on placebo, 43% on 200 mg sotagliflozin, and 49% on 400 mg sotagliflozin, Dr. Buse reported. “The decrease from baseline was highly significant at both doses of sotagliflozin, compared with placebo,” he noted. Adjunctive sotagliflozin therapy also led to significant reductions in bolus insulin doses, fasting blood glucose levels, and body weight as compared with placebo. Drops in body weight averaged 1.6 kg at 200 mg and 2.7 kg at 400 mg, while placebo patients gained an average of 0.8 kg.

There were no deaths during the trial. Rates of treatment-associated adverse events were similar across groups, and serious adverse events affected 3% of placebo patients, 4% of 200-mg patients, and 7% of 400-mg patients. In all, 7% of placebo recipients experienced severe hypoglycemia, compared with 4%-5% of patients on sotagliflozin. The incidence of DKA was 0% on placebo and 1%-3% on sotagliflozin, with a higher rate among patients on pumps, Dr. Buse noted. Most cases of DKA were considered mildly to moderately severe, with blood glucose levels under 250 mg per dL, he added. Sotagliflozin also was associated with dose-dependent increases in rates of diarrhea and genital mycotic infections, which reached about 10% in the 400-mg arm. However, less than 1% of patients stopped treatment because of either adverse event.

“This is the first report of a successful phase III trial of an oral antidiabetic as an adjunct to insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes,” Dr. Buse commented. Sotagliflozin met all prespecified endpoints in the trial, and the 400-mg dose significantly outperformed placebo on each endpoint, he added. A second phase III trial of sotagliflozin (inTandem2) is ongoing, and investigators plan to present pooled data from both trials later this year. Meanwhile, a third phase III trial (inTandem3) is comparing 400 mg sotagliflozin or placebo for patients receiving any type of insulin therapy.

Lexicon Pharmaceuticals developed sotagliflozin and funded the study. Dr. Buse disclosed research funding from Lexicon, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Augmenting optimized insulin with a dual SGLT1-2 inhibitor significantly increased the chances of improved glycemic control without severe hypoglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis in adults with type 1 diabetes.

Major finding: After 24 weeks, 22% of the placebo group achieved this combined endpoint, compared with 44% of patients receiving 400 mg oral daily sotagliflozin (P less than .001) and 34% of patients receiving 200 mg (P = .002).

Data source: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind phase III trial of 793 adults with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: Lexicon Pharmaceuticals developed sotagliflozin and funded the study. Dr. Buse disclosed research funding from Lexicon, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Bedside CGM boosts glucose control in hospital

BY RANDY DOTINGA

SAN DIEGO – Bedside continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with a wireless hookup to a response team allowed doctors and nurses to gain better blood sugar control in hospitalized high-risk patients with diabetes, according to research reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Continuous glucose monitoring and wireless connections can be useful in the hospital setting, not just in the outpatient setting,” said Maria Isabel Garcia, RN, of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute. “They help us to prevent problems rather than fixing them after they happen.”

Research suggests that complications due to dangerous blood sugar levels can lead to longer hospital stays, she noted.

For the study, researchers assigned 45 high-risk hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes to be monitored by DexCom G4 CGM devices. The patients were being treated for a variety of conditions, and all were expected to be hospitalized for more than 2 days.

Researchers housed the normal-sized CGM devices in toolbox-sized containers at bedside. “We don’t want the equipment to get misplaced if the patient has to go from room to room or if the patient is discharged and takes the equipment by mistake,” Ms. Garcia said.

The patients were 43-82 years old (median, 61.4 years; standard deviation, 9.8), 56% male, 73% Hispanic (with 60% preferring to speak Spanish). The mean hemoglobin A1c was 10.2% (SD, 2.3), and the mean body mass index was 32.9 (SD, 8).

The patients were randomized to two groups. In both, the CGM devices were operative and tracked blood sugar levels. In one group, the information was transmitted via wireless hookup to a team of researchers (during the day) or a telemetry team (at night), who were alerted via alarms if blood sugar levels seemed too high or low. The teams would then alert nurses who’d confirm the levels via bedside testing and take appropriate action.

CGM data were gathered from the patients for an average of 4.2 days each (SD, 2.49; range 2-10), and the number of readings per patient ranged from 102 to 2,334 each (median 859.4; SD, 627.8).

The findings suggest that wireless transmission of CGM allowed hospital staff to improve blood sugar control. Readings under 70 mg/dL occurred 0.7% of the time in patients monitored via wireless hookup and 1.4% in the others. Readings over 250 mg/dL appeared 9.8% and 13.2% of the time, respectively and readings over 300 mg/dL appeared 2.6% and 5.1% of the time, respectively.

The investigators plan to recruit 460 patients for the study, Ms. Garcia said. Results may be available within a couple of years, she said.

DexCom provided the CGM devices for the study, which was funded by Diabetes Research Connection and the Confidence Foundation. Ms. Garcia reports no disclosures.

BY RANDY DOTINGA

SAN DIEGO – Bedside continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with a wireless hookup to a response team allowed doctors and nurses to gain better blood sugar control in hospitalized high-risk patients with diabetes, according to research reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Continuous glucose monitoring and wireless connections can be useful in the hospital setting, not just in the outpatient setting,” said Maria Isabel Garcia, RN, of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute. “They help us to prevent problems rather than fixing them after they happen.”

Research suggests that complications due to dangerous blood sugar levels can lead to longer hospital stays, she noted.

For the study, researchers assigned 45 high-risk hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes to be monitored by DexCom G4 CGM devices. The patients were being treated for a variety of conditions, and all were expected to be hospitalized for more than 2 days.

Researchers housed the normal-sized CGM devices in toolbox-sized containers at bedside. “We don’t want the equipment to get misplaced if the patient has to go from room to room or if the patient is discharged and takes the equipment by mistake,” Ms. Garcia said.

The patients were 43-82 years old (median, 61.4 years; standard deviation, 9.8), 56% male, 73% Hispanic (with 60% preferring to speak Spanish). The mean hemoglobin A1c was 10.2% (SD, 2.3), and the mean body mass index was 32.9 (SD, 8).

The patients were randomized to two groups. In both, the CGM devices were operative and tracked blood sugar levels. In one group, the information was transmitted via wireless hookup to a team of researchers (during the day) or a telemetry team (at night), who were alerted via alarms if blood sugar levels seemed too high or low. The teams would then alert nurses who’d confirm the levels via bedside testing and take appropriate action.

CGM data were gathered from the patients for an average of 4.2 days each (SD, 2.49; range 2-10), and the number of readings per patient ranged from 102 to 2,334 each (median 859.4; SD, 627.8).

The findings suggest that wireless transmission of CGM allowed hospital staff to improve blood sugar control. Readings under 70 mg/dL occurred 0.7% of the time in patients monitored via wireless hookup and 1.4% in the others. Readings over 250 mg/dL appeared 9.8% and 13.2% of the time, respectively and readings over 300 mg/dL appeared 2.6% and 5.1% of the time, respectively.

The investigators plan to recruit 460 patients for the study, Ms. Garcia said. Results may be available within a couple of years, she said.

DexCom provided the CGM devices for the study, which was funded by Diabetes Research Connection and the Confidence Foundation. Ms. Garcia reports no disclosures.

BY RANDY DOTINGA

SAN DIEGO – Bedside continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with a wireless hookup to a response team allowed doctors and nurses to gain better blood sugar control in hospitalized high-risk patients with diabetes, according to research reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“Continuous glucose monitoring and wireless connections can be useful in the hospital setting, not just in the outpatient setting,” said Maria Isabel Garcia, RN, of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute. “They help us to prevent problems rather than fixing them after they happen.”

Research suggests that complications due to dangerous blood sugar levels can lead to longer hospital stays, she noted.

For the study, researchers assigned 45 high-risk hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes to be monitored by DexCom G4 CGM devices. The patients were being treated for a variety of conditions, and all were expected to be hospitalized for more than 2 days.

Researchers housed the normal-sized CGM devices in toolbox-sized containers at bedside. “We don’t want the equipment to get misplaced if the patient has to go from room to room or if the patient is discharged and takes the equipment by mistake,” Ms. Garcia said.

The patients were 43-82 years old (median, 61.4 years; standard deviation, 9.8), 56% male, 73% Hispanic (with 60% preferring to speak Spanish). The mean hemoglobin A1c was 10.2% (SD, 2.3), and the mean body mass index was 32.9 (SD, 8).

The patients were randomized to two groups. In both, the CGM devices were operative and tracked blood sugar levels. In one group, the information was transmitted via wireless hookup to a team of researchers (during the day) or a telemetry team (at night), who were alerted via alarms if blood sugar levels seemed too high or low. The teams would then alert nurses who’d confirm the levels via bedside testing and take appropriate action.

CGM data were gathered from the patients for an average of 4.2 days each (SD, 2.49; range 2-10), and the number of readings per patient ranged from 102 to 2,334 each (median 859.4; SD, 627.8).

The findings suggest that wireless transmission of CGM allowed hospital staff to improve blood sugar control. Readings under 70 mg/dL occurred 0.7% of the time in patients monitored via wireless hookup and 1.4% in the others. Readings over 250 mg/dL appeared 9.8% and 13.2% of the time, respectively and readings over 300 mg/dL appeared 2.6% and 5.1% of the time, respectively.

The investigators plan to recruit 460 patients for the study, Ms. Garcia said. Results may be available within a couple of years, she said.

DexCom provided the CGM devices for the study, which was funded by Diabetes Research Connection and the Confidence Foundation. Ms. Garcia reports no disclosures.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: about high or low readings.

Major finding: Readings under 70 mg/dL occurred 0.7% of the time in patients monitored via wireless hookup and 1.4% in other patients. Readings over 250 mg/dL appeared 9.8% and 13.2% of the time, respectively, and readings over 300 mg/dL appeared 2.6% and 5.1% of the time, respectively.

Data source: Early results from a pilot randomized, controlled study of 45 hospitalized, high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. CGM devices measured glucose levels in all patients, but they were only transmitted via wireless hookup to teams in one group.

Disclosures: DexCom provided the CGM machines for the study, which was funded by Diabetes Research Connection and the Confidence Foundation. Garcia reports no disclosures.

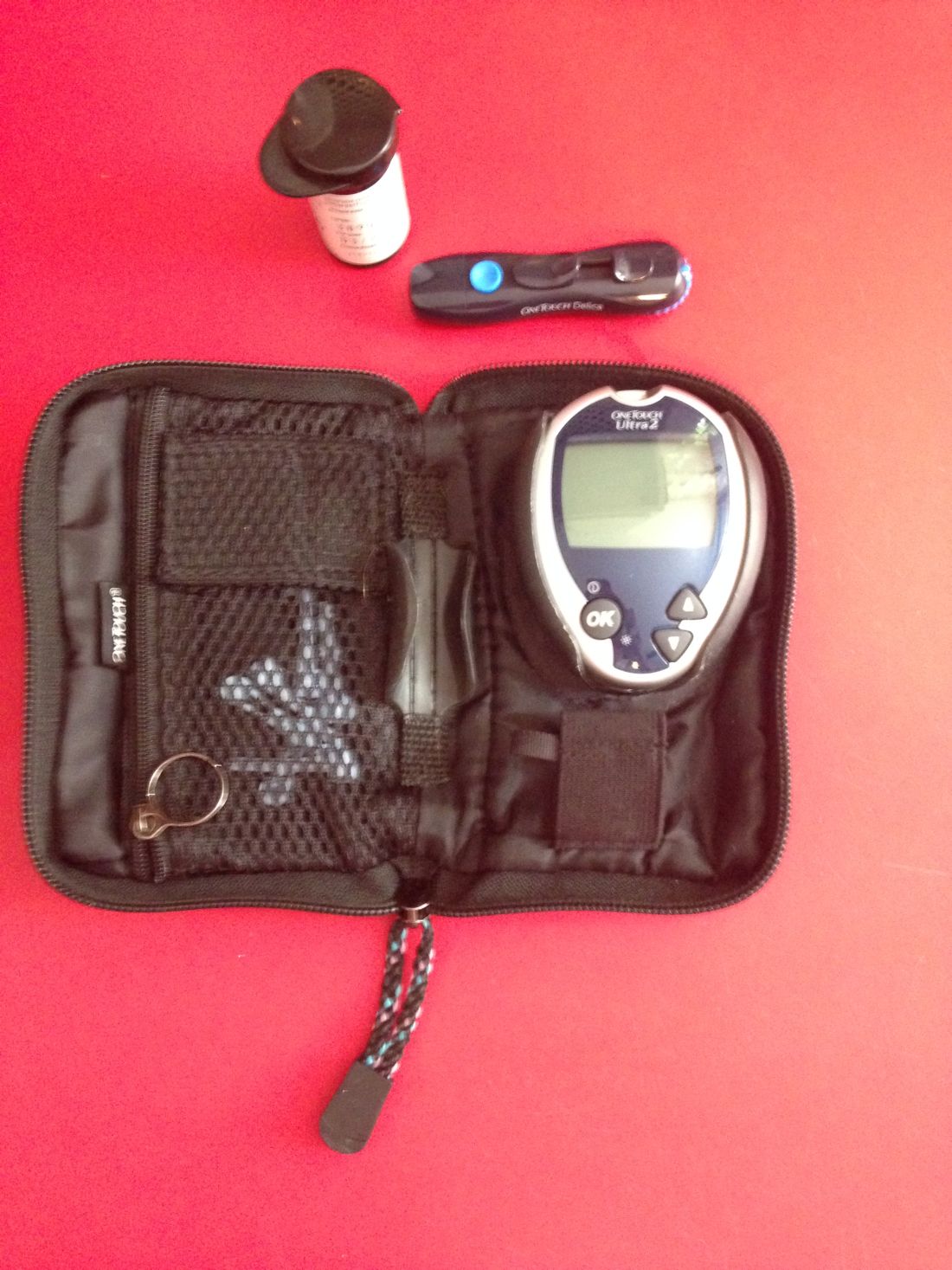

Routine blood glucose monitoring does not improve control or QOL

Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with non–insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) does not appear to make any difference to blood glucose control or quality of life, a new study has found.

The researchers report the results of the Monitor Trial in which 418 patients with non–insulin-treated T2DM were randomized either to once-daily self-monitoring of blood glucose with automatic tailored messages, once-daily monitoring with no messages, and no monitoring. Their report appears in the June 10 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, timed to appear simultaneously with the data’s presentation at the annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association

2017.1233).

Researchers also saw no significant differences in rates of insulin initiation, the incidence of hypoglycemia, or health care utilization.

“This null result occurred despite training participants and primary care clinicians on the use and interpretation of the meter results,” wrote Laura A. Young, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

While the findings reflect data from earlier studies suggesting limited usefulness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in these patients, the authors commented that self-monitoring has persisted as a cornerstone of clinical management of non–insulin-treated T2DM.

“As the first large pragmatic U.S. trial of SMBG [self-monitoring of blood glucose], our findings provide evidence to guide patients and clinicians making important clinical decisions about routine blood glucose monitoring,” they wrote. “Based on these findings, patients and clinicians should engage in dialogue regarding SMBG with the current evidence suggesting that SMBG should not be routine for most patients with non– insulin-treated T2DM.”

The main difference seen between the three groups was in the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities, which the authors said reflected the intervention itself.

Patients taking a GLP-1 agonist at baseline were significantly more likely to increase their dose of the drug if they were in one of the self-monitoring groups, compared with the no-monitoring group, but the authors noted that the numbers were small.

Researchers also saw that African Americans in the self-monitoring with messaging group had significantly lower health-related quality of life scores, compared with the no-monitoring group, although this difference was not seen with the self-monitoring without messaging.

The participants in the trial, which was conducted at 15 primary care practices in central North Carolina, were all older than 30 years and had HbA1c levels between 6.5% and 9.5% in the 6 months before screening.

Compliance rates were similar between the two self-monitoring groups and declined at a similar rate.

The authors cautioned that their study was not powered to examine the effectiveness of self-monitoring versus no monitoring in certain clinical situations, such as the initiation of a new medication or a change in medication dose.

“Proponents of routine SMBG have cited evidence that this testing approach is useful for patients with newly diagnosed diabetes or patients with poorer glycemic control,” they said.” Although disease duration, experience using SMBG, baseline glycemic control, antihyperglycemic treatment, age, race, health literacy, and number of comorbidities made no discernible difference in glycemic control at 52 weeks, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

They also commented on the potential influence of more tailored interventions such as the messaging, saying that while earlier smaller studies had suggested this could be of benefit, this was not shown in their study.

The study was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared grants and nonfinancial support from a range of pharmaceutical companies, and the University of North Carolina licensed its interest in copyright works to Telcare for a glucose messaging and treatment algorithm for the purposes of commercialization.

In most care settings, the statement “you have diabetes” still triggers prescription of a glucometer and instruction on how to perform self-monitoring of blood glucose. Every 3 months thereafter, patients’ glucose logs are reviewed and routine self-monitoring of blood glucose is encouraged, regardless of patients’ risk of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia, because common sense tells us that patients who proactively manage and monitor their diabetes should achieve better outcomes.

The surprising finding of this study make us question the current seemingly common sense–based strategy to encourage routine self-monitoring of blood glucose, and support the Choosing Wisely recommendations of the Society of General Internal Medicine and Endocrine Society that discourage frequent blood glucose monitoring among patients with type 2 diabetes. Routine self-monitoring of blood glucose merits a “less is more” designation because there were no clear benefits accrued, which leaves only possible harms.

Elaine C. Khoong, MD, is from the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and Joseph S. Ross, MD, is from the section of general internal medicine, Yale University School of Medicine and associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017. Jun 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1233 ). Dr. Ross receives research funding through Yale University from Medtronic and the Food and Drug Administration, from Johnson & Johnson, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. No other disclosures were declared.

In most care settings, the statement “you have diabetes” still triggers prescription of a glucometer and instruction on how to perform self-monitoring of blood glucose. Every 3 months thereafter, patients’ glucose logs are reviewed and routine self-monitoring of blood glucose is encouraged, regardless of patients’ risk of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia, because common sense tells us that patients who proactively manage and monitor their diabetes should achieve better outcomes.

The surprising finding of this study make us question the current seemingly common sense–based strategy to encourage routine self-monitoring of blood glucose, and support the Choosing Wisely recommendations of the Society of General Internal Medicine and Endocrine Society that discourage frequent blood glucose monitoring among patients with type 2 diabetes. Routine self-monitoring of blood glucose merits a “less is more” designation because there were no clear benefits accrued, which leaves only possible harms.

Elaine C. Khoong, MD, is from the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and Joseph S. Ross, MD, is from the section of general internal medicine, Yale University School of Medicine and associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017. Jun 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1233 ). Dr. Ross receives research funding through Yale University from Medtronic and the Food and Drug Administration, from Johnson & Johnson, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. No other disclosures were declared.

In most care settings, the statement “you have diabetes” still triggers prescription of a glucometer and instruction on how to perform self-monitoring of blood glucose. Every 3 months thereafter, patients’ glucose logs are reviewed and routine self-monitoring of blood glucose is encouraged, regardless of patients’ risk of hypoglycemia or severe hyperglycemia, because common sense tells us that patients who proactively manage and monitor their diabetes should achieve better outcomes.

The surprising finding of this study make us question the current seemingly common sense–based strategy to encourage routine self-monitoring of blood glucose, and support the Choosing Wisely recommendations of the Society of General Internal Medicine and Endocrine Society that discourage frequent blood glucose monitoring among patients with type 2 diabetes. Routine self-monitoring of blood glucose merits a “less is more” designation because there were no clear benefits accrued, which leaves only possible harms.

Elaine C. Khoong, MD, is from the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and Joseph S. Ross, MD, is from the section of general internal medicine, Yale University School of Medicine and associate editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2017. Jun 10. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1233 ). Dr. Ross receives research funding through Yale University from Medtronic and the Food and Drug Administration, from Johnson & Johnson, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, and from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. No other disclosures were declared.

Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with non–insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) does not appear to make any difference to blood glucose control or quality of life, a new study has found.

The researchers report the results of the Monitor Trial in which 418 patients with non–insulin-treated T2DM were randomized either to once-daily self-monitoring of blood glucose with automatic tailored messages, once-daily monitoring with no messages, and no monitoring. Their report appears in the June 10 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, timed to appear simultaneously with the data’s presentation at the annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association

2017.1233).

Researchers also saw no significant differences in rates of insulin initiation, the incidence of hypoglycemia, or health care utilization.

“This null result occurred despite training participants and primary care clinicians on the use and interpretation of the meter results,” wrote Laura A. Young, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

While the findings reflect data from earlier studies suggesting limited usefulness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in these patients, the authors commented that self-monitoring has persisted as a cornerstone of clinical management of non–insulin-treated T2DM.

“As the first large pragmatic U.S. trial of SMBG [self-monitoring of blood glucose], our findings provide evidence to guide patients and clinicians making important clinical decisions about routine blood glucose monitoring,” they wrote. “Based on these findings, patients and clinicians should engage in dialogue regarding SMBG with the current evidence suggesting that SMBG should not be routine for most patients with non– insulin-treated T2DM.”

The main difference seen between the three groups was in the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities, which the authors said reflected the intervention itself.

Patients taking a GLP-1 agonist at baseline were significantly more likely to increase their dose of the drug if they were in one of the self-monitoring groups, compared with the no-monitoring group, but the authors noted that the numbers were small.

Researchers also saw that African Americans in the self-monitoring with messaging group had significantly lower health-related quality of life scores, compared with the no-monitoring group, although this difference was not seen with the self-monitoring without messaging.

The participants in the trial, which was conducted at 15 primary care practices in central North Carolina, were all older than 30 years and had HbA1c levels between 6.5% and 9.5% in the 6 months before screening.

Compliance rates were similar between the two self-monitoring groups and declined at a similar rate.

The authors cautioned that their study was not powered to examine the effectiveness of self-monitoring versus no monitoring in certain clinical situations, such as the initiation of a new medication or a change in medication dose.

“Proponents of routine SMBG have cited evidence that this testing approach is useful for patients with newly diagnosed diabetes or patients with poorer glycemic control,” they said.” Although disease duration, experience using SMBG, baseline glycemic control, antihyperglycemic treatment, age, race, health literacy, and number of comorbidities made no discernible difference in glycemic control at 52 weeks, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

They also commented on the potential influence of more tailored interventions such as the messaging, saying that while earlier smaller studies had suggested this could be of benefit, this was not shown in their study.

The study was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared grants and nonfinancial support from a range of pharmaceutical companies, and the University of North Carolina licensed its interest in copyright works to Telcare for a glucose messaging and treatment algorithm for the purposes of commercialization.

Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with non–insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) does not appear to make any difference to blood glucose control or quality of life, a new study has found.

The researchers report the results of the Monitor Trial in which 418 patients with non–insulin-treated T2DM were randomized either to once-daily self-monitoring of blood glucose with automatic tailored messages, once-daily monitoring with no messages, and no monitoring. Their report appears in the June 10 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, timed to appear simultaneously with the data’s presentation at the annual meeting of the American Diabetes Association

2017.1233).

Researchers also saw no significant differences in rates of insulin initiation, the incidence of hypoglycemia, or health care utilization.

“This null result occurred despite training participants and primary care clinicians on the use and interpretation of the meter results,” wrote Laura A. Young, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

While the findings reflect data from earlier studies suggesting limited usefulness of self-monitoring of blood glucose in these patients, the authors commented that self-monitoring has persisted as a cornerstone of clinical management of non–insulin-treated T2DM.

“As the first large pragmatic U.S. trial of SMBG [self-monitoring of blood glucose], our findings provide evidence to guide patients and clinicians making important clinical decisions about routine blood glucose monitoring,” they wrote. “Based on these findings, patients and clinicians should engage in dialogue regarding SMBG with the current evidence suggesting that SMBG should not be routine for most patients with non– insulin-treated T2DM.”

The main difference seen between the three groups was in the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities, which the authors said reflected the intervention itself.

Patients taking a GLP-1 agonist at baseline were significantly more likely to increase their dose of the drug if they were in one of the self-monitoring groups, compared with the no-monitoring group, but the authors noted that the numbers were small.

Researchers also saw that African Americans in the self-monitoring with messaging group had significantly lower health-related quality of life scores, compared with the no-monitoring group, although this difference was not seen with the self-monitoring without messaging.

The participants in the trial, which was conducted at 15 primary care practices in central North Carolina, were all older than 30 years and had HbA1c levels between 6.5% and 9.5% in the 6 months before screening.

Compliance rates were similar between the two self-monitoring groups and declined at a similar rate.

The authors cautioned that their study was not powered to examine the effectiveness of self-monitoring versus no monitoring in certain clinical situations, such as the initiation of a new medication or a change in medication dose.

“Proponents of routine SMBG have cited evidence that this testing approach is useful for patients with newly diagnosed diabetes or patients with poorer glycemic control,” they said.” Although disease duration, experience using SMBG, baseline glycemic control, antihyperglycemic treatment, age, race, health literacy, and number of comorbidities made no discernible difference in glycemic control at 52 weeks, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

They also commented on the potential influence of more tailored interventions such as the messaging, saying that while earlier smaller studies had suggested this could be of benefit, this was not shown in their study.

The study was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared grants and nonfinancial support from a range of pharmaceutical companies, and the University of North Carolina licensed its interest in copyright works to Telcare for a glucose messaging and treatment algorithm for the purposes of commercialization.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with non–insulin-treated T2DM who do not use routine self-monitoring of blood glucose show the same blood glucose control and health-related quality of life as those who do self-monitor.

Data source: A 1-year open-label randomized trial in 418 patients with T2DM.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Two authors declared grants and nonfinancial support from a range of pharmaceutical companies, and the University of North Carolina licensed its interest in copyright works to Telcare for a glucose messaging and treatment algorithm for the purposes of commercialization.