While febrile seizures are common in early childhood and generally benign, prolonged febrile seizures of 30 minutes or longer have been associated with a greatly increased risk of later epilepsy, particularly temporal lobe epilepsy.

To better understand the pathogenesis of epilepsy among children presenting with febrile status epilepticus (FSE) and to guide the development of interventions that could prevent it following a first episode of FSE, a group of clinical researchers has been working with a cohort of 199 children aged 1 month to 6 years (median age, 15.8 months) who presented with FSE between 2003 and 2010.

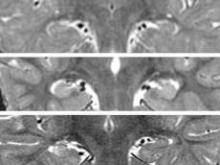

Courtesy Dr. Shlomo Shinnar

Courtesy Dr. Shlomo Shinnar

The range of hippocampal pathology shown by MRI T2 intensity after febrile status epilepticus varies from normal hippocampi (top, 15-month-old) to slightly increased intensity and reduced anatomical landmarks (middle, left hippocampus in a 3-year-old) to markedly increased intensity (bottom, lateral inferior aspect of the right hippocampus, near CA1, in a 13-month-old).

The study, being conducted at five clinical sites in the United States under funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is designed with a considerable follow-up, with data collection planned for 1, 5, 10, and 15 years after the initial acute episode.

But even with the first-year results yet to be published, the Consequences of Prolonged Febrile Seizures in Childhood, or FEBSTAT, study has already generated some important findings.

Human herpes viruses 6 and 7 are strongly associated with FSE, the FEBSTAT team revealed this June, with HHV-6b or 7 infections occurring in 32% of 169 children in the cohort (Epilepsia 2012;53:1481-8). Whether there is a relationship between HHV infection at baseline and subsequent epilepsy will take years to establish.

In July, the FEBSTAT investigators published results of a study showing that 11.5% of 191 children in the cohort had MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) evidence of an acute injury to one hippocampus following FSE (Neurology 2012;79:871-7), compared with none in a control group of children presenting with benign febrile seizures. A substantial number of cases also had developmental abnormalities of the hippocampus (10.5%); but some children in the control group also had abnormalities (2.1%).

In November, the researchers revealed that of acute EEG findings following FSE, 45.2% were abnormal, with the most common abnormality being focal slowing or attenuation. Epileptiform abnormalities also were seen in 6.5% of the full cohort of 199 children (Neurology 2012 Nov. 7 [doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182759766]). The EEG findings are highly associated with MRI evidence of acute hippocampal injury, and may also reveal injuries too subtle to be picked up by MRI imaging.

FEBSTAT principal investigator Dr. Shlomo Shinnar, professor of neurology, pediatrics, and epidemiology at Montefiore Medical Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, said in an interview that MRI and EEG are used in tandem to offer the most complete picture possible.

"Sometimes the EEG will show you’re evolving into epilepsy when the MRI doesn’t; sometimes the MRI will show changes before the EEG. We want multimodal assessments, so whenever we do an MRI we do an EEG. EEG is noninvasive and minimal risk; it turns out to be quite predictive and it is very easy to get."