Mr. L, age 35, has an appointment at a mental health clinic for ongoing treatment of depression. His medication list includes atorvastatin, bupropion, lisinopril, and cranberry capsules for non-descriptive urinary issues. He has been treated for some time at a different outpatient facility; however he recently moved and changed clinics.

At this visit, his first, Mr. L receives a full physical exam, including a urine drug screen point-of-care (POC) test. He informs the nurse that he has an extensive history of drug abuse: “You name it, I’ve done it.” Although he experimented with many illicit substances, he acknowledges that “downers” were his favorite. He believes that his drug abuse could have caused his depression, but is proud to declare that he has been “clean” for 12 months and his depression is approaching remission.

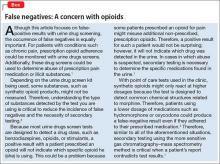

However, the urine drug screen is positive for amphetamines. Mr. L vehemently swears that the test must be wrong, restating that he has been clean for 12 months. “Besides, I don’t even like ‘uppers’!” Because of Mr. L’s insistence, the clinician does a brief literature search about false-positive results in urine drug screening, which shows that, rarely, bupropion can trigger a false positive in the amphetamine immunoassay.

Could this be a false-positive result? Or is Mr. L not telling the truth?

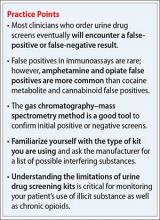

Because no clinical lab test is perfect, any clinician who runs urine drug screens will encounter a false-positive result. (See the Box,1-3 for discussion of false negatives.) Understanding how each test works—and potential sources of error— can help you evaluate test results and determine the best course of action.

There are 2 main methods involved in urine drug testing: in-office (POC) urine testing and laboratory-based testing. This article describes the differences between these tests and summarizes the potential for false-positive results.

In-office urine testing

POC tests in urine drug screens use a technique called “immunoassay,” which is quantitative and generally will detect the agent in urine for only 3 to 7 days after ingestion.4 This test relies on the principle of competitive binding: If a parent drug or metabolite is present in urine, it will bind to a specific antibody site on the test strip and produce a positive result.5 Other compounds that are similarly “shaped” on a molecular level also can bind to these antibody sites when present in sufficient quantity, producing a “cross reaction,” also called a “false-positive” result. The Table6 lists agents that can cross-react with immunoassay tests. In addition to the cross-reaction, false positives also can occur because of technician or clerical error— making it important to review the process by which the specimen was obtained and tested if a false-positive result is suspected, as in the case described here.7

Different POC tests can have varying cross-reactivity patterns, based on the antibody used.8 In general, false positives in immunoassays are rare, but amphetamine and opiate false positives are more common than cocaine metabolite and cannabinoid false positives.9 The odds of a false positive vary, depending on the specificity of the immunoassay used and the substance under detection.6

A study that analyzed 10,000 POC urine drug screens found that 362 specimens tested positive for amphetamines, but that 128 of those did not test positive for amphetamines using more sensitive tests.10 Of these 128 false positives reported, 53 patients were taking bupropion at the time of the test.10 Therefore, clinicians should do a thorough patient medication review at the time of POC urine drug testing. In addition, consider identifying which type of test you are using at your practice site, and ask the manufacturer or lab to provide a list of known possible false positives.

Laboratory-based GC–MS testing

If a false positive is suspected on a POC immunoassay-based urine drug screen, results can be confirmed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Although GC–MS is more accurate than an immunoassay, it also is more expensive and time-consuming.9

GC–MS breaks down a specimen into ionized fragments and separates them based on their mass–charge ratio. Because of this, GC–MS is able to identify the presence of a specific drug (eg, oxycodone) instead of a broad class (eg, opioid). The GC–MS method is a good tool to confirm initial positive screens when their integrity is in question because, unlike POC tests used during an office visit, GC–MS is not influenced by cross-reacting compounds.11-13

GC–MS is not error-free, however. For example, heroin and hydrocodone are metabolized into morphine and hydromorphone, respectively. Depending on when the specimen was collected, the metabolites, not the parents, might be the compounds identified, which might produce confusing results.