First described in 1996, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) exhibits a wide clinical spectrum and is definitively diagnosed through computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of the brain.1 Clinical presentation may include a spectrum of symptoms, including nausea, emesis, seizures, visual loss, paralysis, and headaches.2,3 The most common imaging finding of PRES is bilateral foci of vasogenic edema located in the parieto-occipital white matter.2-6 Other areas of the brain are frequently affected as well, with the frontal and temporal lobes and the basal or cortical ganglia showing signs of distinctly noncytotoxic edema in 12.5% to 54.2% of all cases.3 With the symptom of visual loss being present in 20% to 62.5% of patients with PRES, the syndrome constitutes a rare potential cause for postoperative visual loss (POVL) after spinal surgery, which has a generally good prognosis because most patients will completely regain their eyesight.2,3

We present a unique account of 2 patients who underwent extensive spinal surgery and received a timely diagnosis and treatment of PRES at a single institution. We aim to elucidate the difference in clinical and radiographic presentation of PRES in relation to other known causes of POVL after spinal surgery. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

Clinical Presentation. A 78-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with disability due to severe lower back pain. Her surgical history was significant for breast lumpectomy and cataract excision. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, obesity (body mass index, 31.5), hypercholesterolemia, emphysema, and anemia. She had undergone spinal surgery, specifically laminectomies from L2 to S1. The radiographic examination showed degenerative thoracolumbar scoliosis with severe spondylosis, disc space collapse, and ankylosis of L4-L5 (Figure 1).

Operative Procedure. The patient underwent transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion (XLIF, NuVasive) from L1 to L4 and posterior spinal fusion from T10 to pelvis (Expedium, Depuy Synthes) (Figure 2). Operative time was 553 minutes; estimated blood loss was 2000 mL due to intraoperative coagulopathy (platelets, 40,000/µL) near the end of the posterior portion of the procedure. Intraoperative hypotension was treated by volume resuscitation and transient use of vasopressor agents. She was transfused with 1700 mL of blood, 150 mL of saline solution, and 420 mL of Lactated Ringer’s solution. No intraoperative complications occurred. The patient was extubated uneventfully on postoperative day 1 and was at baseline neurologically with no visual disturbances.

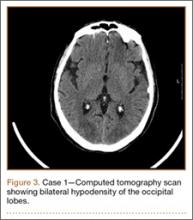

Development and Diagnosis of PRES. The patient made significant progress with physical therapy and developed episodes of hypertension at night on postoperative days 4 to 6. Her mean peak systolic blood pressure was 180 mm Hg. This improved after oral beta-blocker therapy. On postoperative day 6, the patient was ambulating with physical therapy and the aid of a walker. She was found to be neurologically intact, was resting comfortable in a chair reading a book, and was cleared for transfer to a rehabilitation facility the next day. During the morning on postoperative day 7, she developed confusion and visual loss. The patient reported blurry vision followed by complete bilateral painless loss of vision aside from mild light perception. She was unable to identify any objects. She had extinction to double simultaneous stimuli and evidence of agraphesthesia in the left hand. Her neurologic examination was otherwise at baseline. Upon emergent imaging, head CT showed bilateral symmetric areas of hypodensity involving the cortical and subcortical white matter of both occipital lobes (Figure 3). MRI showed extensive bilateral cortical and subcortical signal hyperintensity involving the parietal and occipital lobes (Figure 4). No evidence of petechial or lobar hemorrhage was found.

Treatment and Clinical Course. The patient was transferred to the neurology intensive care unit for neurologic monitoring. She was treated aggressively for recurrent hypertensive episodes. Twenty-four hours after initial blood pressure optimization therapy, she partially recovered her eyesight. She exhibited complete recovery after 48 hours. The patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility in stable condition on postoperative day 11.

Case 2

Clinical Presentation. A 51-year-old woman presented to the outpatient clinic with progressive low back pain and decompensation due to degenerative adult scoliosis. Her surgical history was significant for an uneventful Caesarean section. Her medical history was significant for borderline hypertension and obesity (body mass index, 34.4). The radiographic examination showed an S-shaped thoracolumbar curve from T4 to L4 (Figure 5).

Operative Procedure. After discussions about the risks and benefits of the procedure, the patient underwent posterior spinal fusion from T3 to pelvis (Mesa, K2M) and interbody fusion from L4 to S1 via a presacral approach using the AxiaLIF system (TranS1) (Figure 6). The operation spanned 507 minutes. The patient lost approximately 2200 mL of blood. She was transfused with 1690 mL of blood, 1250 mL of Lactated Ringer’s solution, and 1 unit (50 mL) of albumin. No intraoperative complications occurred.