Osteochondromas are common benign bone tumors composed of a bony protrusion with an overlying cartilage cap.1 This lesion constitutes 24% to 40% of all benign bone tumors, and the great majority arise from the metaphyseal region of long bones.2 The scapula accounts for only 3% to 5% of all osteochondromas; however, this lesion is the most common benign bone tumor to involve the scapula.3

In contrast, cutaneous bronchogenic cyst of the scapula is an exceedingly rare pathology. The bronchogenic cyst is a congenital cystic mass lined by tracheobronchial structures and respiratory epithelium.4 These are most commonly located in the thorax, although numerous remote locations have also been described, including cutaneous cysts.5 The overall incidence of bronchogenic cysts is thought to be 1 in 42,000 to 1 in 68,000.6 There are only 15 case reports of cutaneous bronchogenic cysts in the scapular region.7

We report the case of a novel dual lesion of both an osteochondroma and a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst in the scapula. The patient’s guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 12-month-old boy presented to our clinic with the complaint of a mass over the left scapula. The mass was first noted incidentally several weeks earlier during bathing. Examination revealed a firm, subcutaneous, nontender mass measuring 1×2 cm located over the spine of the scapula. There were no overlying skin changes, and there was normal function of the ipsilateral upper extremity. Anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs revealed no abnormality. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an exostosis projecting from the scapular spine measuring 2×6×7 mm with an adjacent cystic mass measuring 5×8×9 mm that was thought to represent bursitis (Figure 1). The decision was made to observe the mass.

The patient returned to clinic at age 31 months with a new complaint of scant drainage of serous fluid from a pinprick-sized hole located just superolateral to the scapular mass. The child’s mother reported daily manual expression of fluid from the mass via the hole, without which the mass would enlarge. There were no local or systemic signs of infection. A repeat MRI again revealed an exostosis with an adjacent cystic mass with interval enlargement of the cyst (Figure 2). At age 4.5 years, the decision was made to proceed with excision of the osteochondroma and adjacent cystic mass.

The mass was approached via a 2-cm incision designed to excise the tract to the skin. Dissection revealed a sinus tract connecting to a well-defined cystic sac. This sac was attached to the underlying exostosis. The exostosis and attached cyst were excised en bloc. The cyst was opened, revealing foul-smelling, cloudy white fluid that was sent for culture; the specimen was sent for pathology.

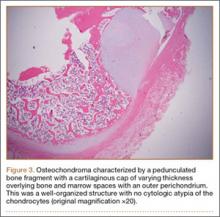

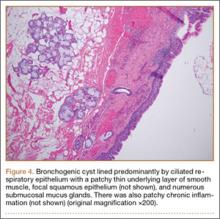

The fluid culture grew mixed flora, with no Staphylococcus aureus, group A streptococcus, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa identified. The pathologic examination identified bone with a cartilaginous cap, consistent with osteochondroma (Figure 3), as well as a cyst lined by respiratory epithelium with patchy areas of squamous epithelium and surrounding mucus glands, consistent with bronchogenic cyst (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the contiguous nature of the 2 lesions.

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient returned to full use of the left upper extremity and had resolution of all drainage.

Discussion

Osteochondromas are thought to arise from aberrant growth of the epiphyseal growth plate cartilage. A small portion of the physis herniates past the groove of Ranvier and grows parallel to the normal physis with medullary continuity. This can occur idiopathically or, more rarely, secondary to an identified injury to the growth plate.1

The formation of bronchogenic cysts is most often attributed to anomalous budding of the ventral foregut during fetal development,4 hence the alternative designation of these cysts as foregut cysts. An extrathoracic location of the cyst has been postulated to stem from 2 possible events: a preexisting cyst may migrate out of the thorax prior to closure of the sternal plates, or sternal plate closure may itself pinch off the cyst.8,9 An alternative explanation is in situ metaplastic development of respiratory epithelium.10 When located near the skin, these cysts often drain clear fluid.11

Scapular osteochondromas are known to cause various pathologies of the shoulder girdle, including snapping scapula syndrome, chest wall deformity, shoulder impingement, and bursa formation.12-17 This case, however, is the first known finding of a scapular osteochondroma with a contiguous cutaneous bronchogenic cyst. A putative explanation for their co-occurrence is that local disturbances caused by one lesion stimulated the formation of the second. The direct connection between the bronchogenic cyst and the bone, as has been reported in 3 cases,7,9,18 seems to favor this explanation. Definitive conclusions regarding any causal relationship are beyond the scope of this single case report.