Mrs. J, age 49, presents to your psychiatric clinic. For the last few years, she has been experiencing night sweats and hot flashes, which she has attributed to being perimenopausal. Over the last year, she has noticed that her mood has declined; however, she has suffered several life events that she feels have contributed. Her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and had to move into a nursing home, which Mrs. J found very stressful. At the same time, her daughter left home for college, and her son is exploring his college options. Recently, Mrs. J has not been able to work due to her mood, and she is afraid she may lose her job as a consequence. She has struggled to talk to her husband about how she is feeling, and feels increasingly isolated. Over the last month, she has had increased problems sleeping and less energy; some days she struggles to get out of bed. She is finding it difficult to concentrate and is more forgetful. She has lost interest in her hobbies and is no longer meeting with her friends. She has no history of depression or anxiety, although she recalls feeling very low in mood for months after the birth of each of her children.

Are Mrs. J’s symptoms related to menopause or depression? What further investigations are necessary? Would you modify your treatment plan because of her menopausal status?

Women are at elevated risk of developing psychiatric symptoms and disorders throughout their reproductive lives, including during menopause. Menopause is a time of life transition, when women may experience multiple physical symptoms, including vasomotor symptoms (night sweats and hot flashes), sexual symptoms, and sleep difficulties. Depressive symptoms occur more frequently during menopause, and symptoms of schizophrenia may worsen.

Estrogen plays a role in mental illness throughout a woman’s life. In menopause, decreasing estrogen levels may correlate with increased mood symptoms, physical symptoms, and psychotic symptoms. As such, psychiatrists should consider whether collaboration regarding adjunctive hormone replacement therapy would be beneficial, and whether the benefits outweigh the potential risks. Otherwise, treatment of depression in menopause is similar to treatment outside of the menopausal transition, though serotonergic antidepressants may help target vasomotor symptoms while therapy may focus on role transition and loss. In this article, we review why women are at increased risk for mental illness during menopause, the role of estrogen, and treatment of mood and psychotic disorders during this phase of a woman’s life.

Increased vulnerability across the lifespan

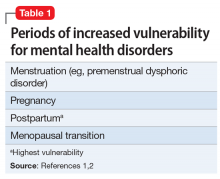

The female lifecycle includes several periods of increased vulnerability to mental illness related to reproductive hormones and life changes. Compared with men, women have approximately twice the risk of developing depression in their lifetime.1 With the onset of menarche, the increased risk of mental health problems begins (Table 11,2). Women are at elevated risk of mood disorders in both pregnancy and postpartum; approximately one-seventh to one-quarter of women experience postpartum depression, depending on the population studied. Finally, women are at risk of mood difficulties in the perimenopause. Those with a history of depression are at particularly elevated risk in the perimenopause.2

Continued to: Why menopause?