Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

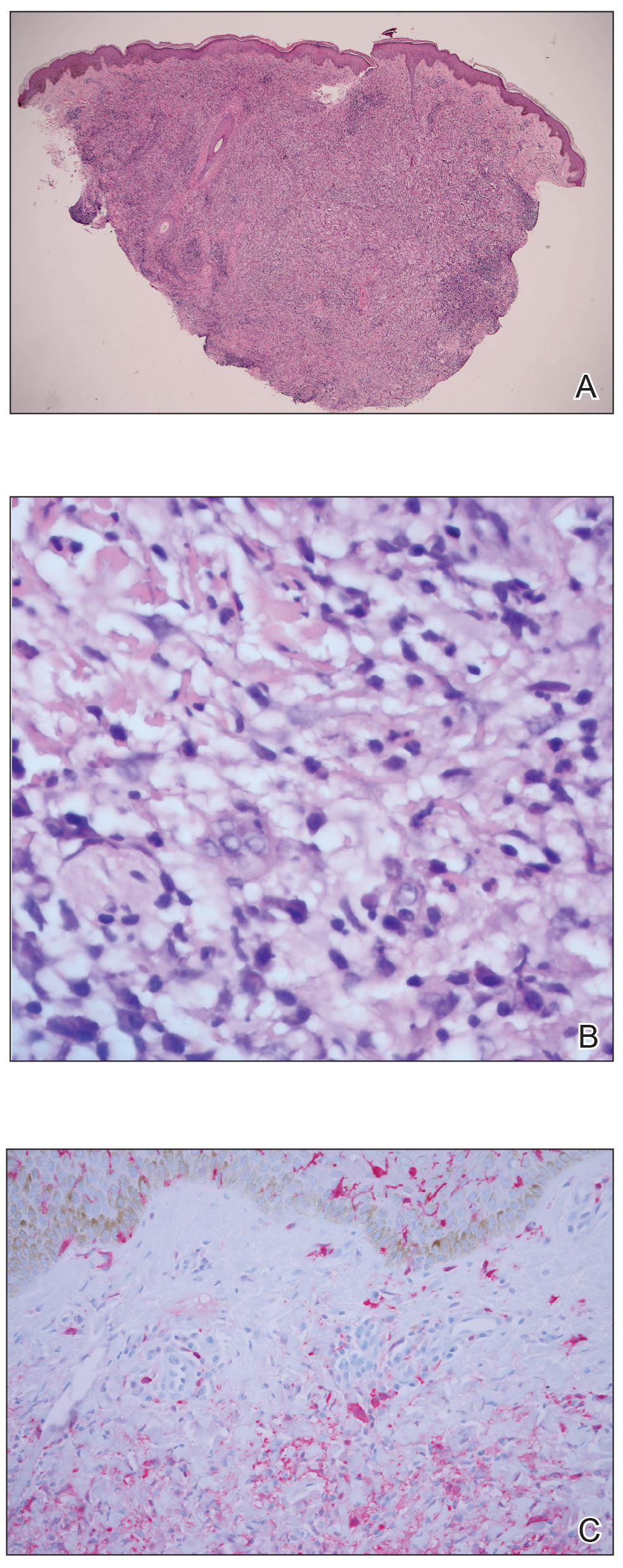

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Figure 2. A, A punch biopsy showed histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E, original magnification ×4). B, Emperipolesis was noted (H&E, original magnification ×60). C, Histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (original magnification ×10).

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2