User login

Granular Parakeratosis

To the Editor:

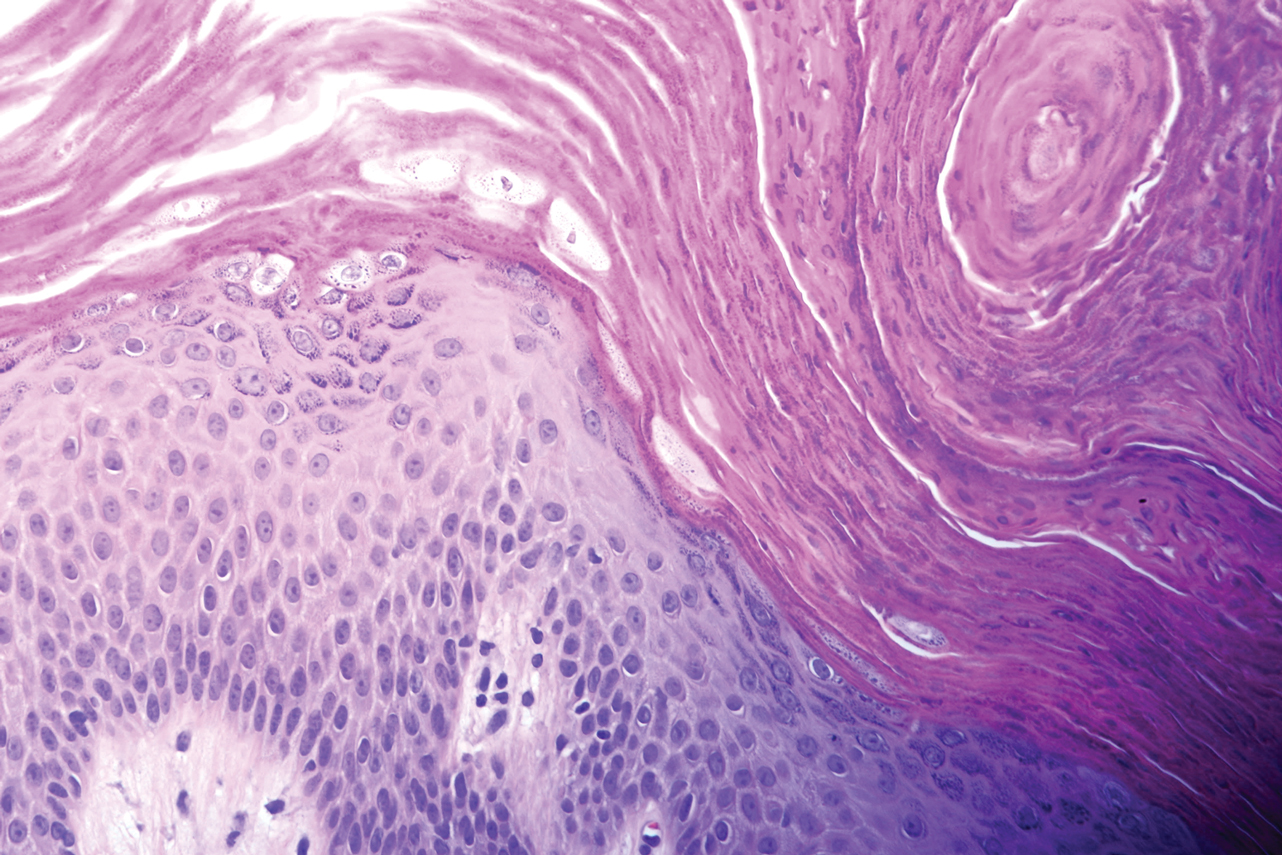

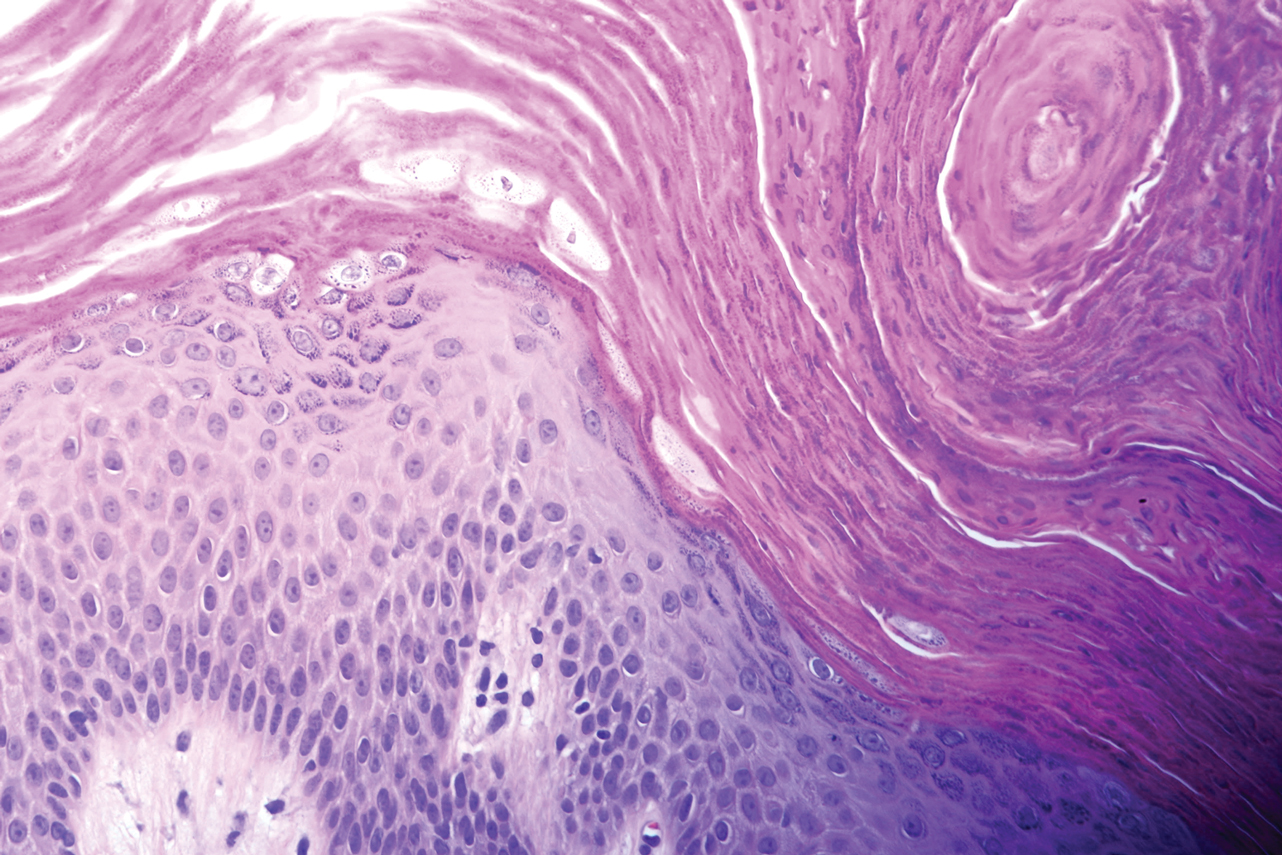

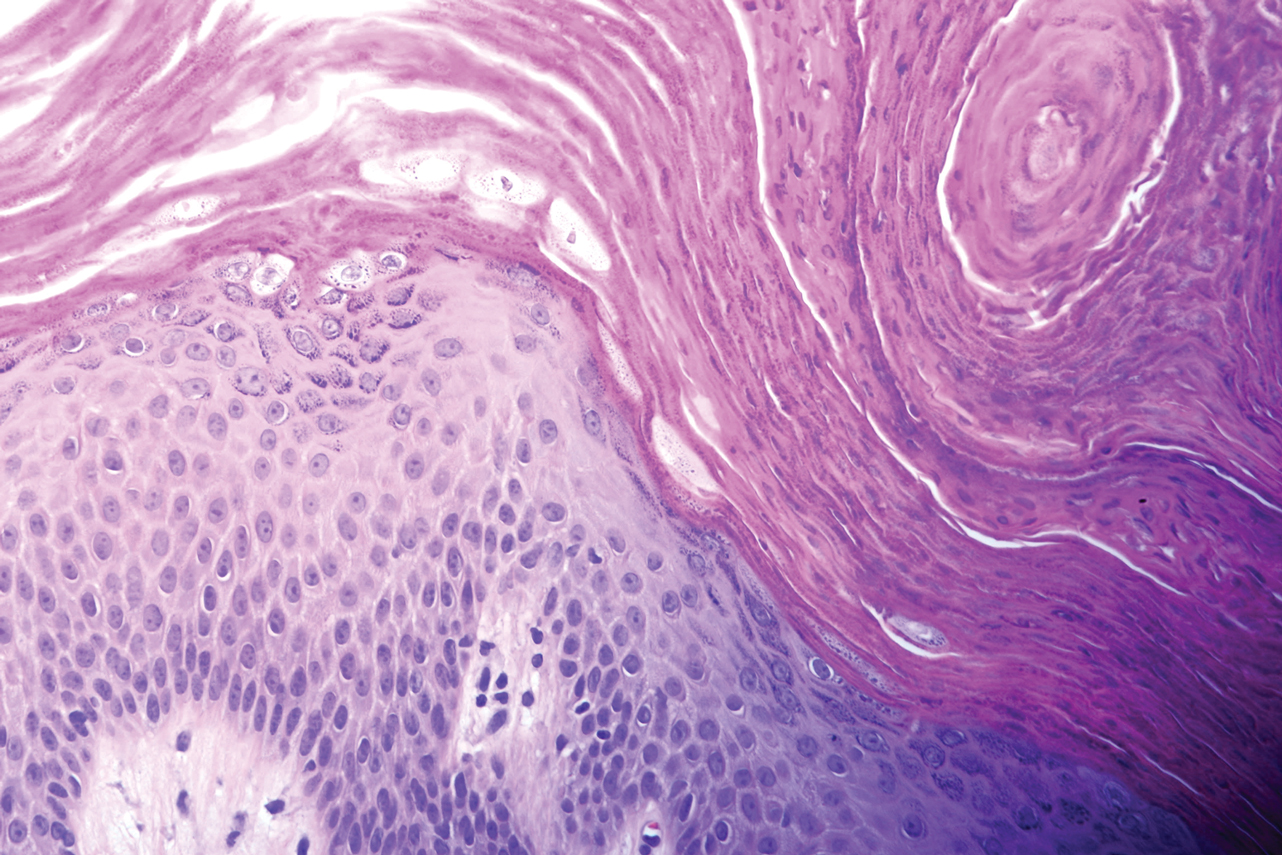

A 46-year-old overweight woman presented with a rash in the axillae of 2 months’ duration. She did not report any additional symptoms such as pruritus or pain. She reported changing her deodorant recently from Secret Original to Secret Clinical Strength (both Procter & Gamble). Her medical history was remarkable for asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical examination revealed erythematous-brown, stuccolike, hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques in recently shaved axillae, affecting the left axilla more than the right axilla (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included granular parakeratosis, intertrigo, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic keratoses, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed a marked compact parakeratotic horn with retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). The subjacent epidermis showed some acanthosis and spongiosis with mild chronic inflammation of the dermal rim. Based on histopathology, granular parakeratosis was diagnosed.

At a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, we prescribed glycolic acid lotion 10% applied to the axillae twice daily, plus tretinoin gel 0.05% applied to the axillae each evening. She reported clearing after 1 week of therapy. She also had changed her deodorant from Secret Clinical Strength back to the usual Secret Original. The patient discontinued topical treatment after clearing of the lesions. Three weeks later, clinical examination revealed postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the axillae, and the prior lesions had resolved (Figure 3).

Granular parakeratosis is an unusual condition most commonly presenting in middle-aged women in the axillae, with a clinical presentation of erythematous to brownish hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques. Although few cases have been reported, granular parakeratosis likely is more common than has been reported. There have been reports involving the scalp, cheeks, abdomen, thighs, and other intertriginous areas including inguinal folds and the submammary region.1-4 There also is an infantile form related to diapers and zinc oxide paste.5 Although uncommon, granular parakeratosis can occur as a single papule or plaque and is termed granular parakeratotic acanthoma.6 Lesions may persist for months, spontaneously resolve and recur, and occasionally evolve into fissures and erosions due to irritation. Pruritus is a common concern. Histology of granular parakeratosis reveals hyperkeratosis with eosinophilic staining, compact parakeratosis with retention of basophilic keratohyalin granules, and vascular proliferation and ectasia.5

The cause is unknown but possibly related to irritation from rubbing, occlusion, sweating, or deodorants.5,7 Cases indicate a link to obesity. Hypotheses as to the etiology include the disruption of cornification. Normally, filaggrin maintains the keratohyaline granules in the stratum corneum during cornification. Therefore, the retention of keratohyaline granules in granular parakeratosis may be due to a defect in processing profilaggrin to filaggrin, which has been proposed based on ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies.8

The differential diagnosis includes granular parakeratosis, intertrigo (caused by seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, or erythrasma), Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. The papules may resemble seborrheic keratoses, while the plaques can be mistaken for acanthosis nigricans.

Therapeutic success has been reported with topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, topical or oral retinoids, ammonium lactate, calcineurin inhibitors, topical or oral antifungals, cryotherapy, and botulinum toxin injections.3,9-11 In addition, parakeratosis has decreased in biopsies from psoriatic patients after acitretin, methotrexate, and phototherapy, which may be alternative treatments for unusually difficult or recalcitrant cases of granular parakeratosis. To minimize side effects and resolve the papules quickly, we combined 2 synergistic agents—glycolic acid and tretinoin—each with different mechanisms of action, and we observed excellent clinical response.

Granular parakeratosis is possibly related to a combination of topical products that potentiate irritation, rubbing, and occlusion of sweat. Multiple treatment modalities likely contribute to clearing, the most important being removal of any triggering topical products. Our patient’s change in deodorant may have been the inciting factor for the disease. Withdrawal of the Secret Clinical Strength deodorant prompted clearing, though topical retinoid and glycolic acid acted as facilitating therapies for timely results. A thorough history, as highlighted by this case, may help pinpoint etiologic factors. By identifying a seemingly innocuous change in hygienic routine, we were able to minimize the need for ongoing therapy.

- Graham R. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:AB45-AB45.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Channual J, Fife DJ, Wu JJ. Axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2013;92;61, 65-66.

- Streams S, Gottwald L, Zaher A, et al. Granular parakeratosis of the scalp: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:AB81-AB81.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2015.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Granular parakeratotic acanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:393-396.

- Naylor E, Wartman D, Telang G, et al. Granular parakeratosis secondary to postsurgical occlusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB126.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2012.

- Baum B, Skopit S. Granular parakeratosis treatment with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment: a case presentation and discussion. J Am Osteo Coll Dermatol. 2013;26:40-41.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S279-S280.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:789790.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old overweight woman presented with a rash in the axillae of 2 months’ duration. She did not report any additional symptoms such as pruritus or pain. She reported changing her deodorant recently from Secret Original to Secret Clinical Strength (both Procter & Gamble). Her medical history was remarkable for asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical examination revealed erythematous-brown, stuccolike, hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques in recently shaved axillae, affecting the left axilla more than the right axilla (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included granular parakeratosis, intertrigo, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic keratoses, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed a marked compact parakeratotic horn with retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). The subjacent epidermis showed some acanthosis and spongiosis with mild chronic inflammation of the dermal rim. Based on histopathology, granular parakeratosis was diagnosed.

At a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, we prescribed glycolic acid lotion 10% applied to the axillae twice daily, plus tretinoin gel 0.05% applied to the axillae each evening. She reported clearing after 1 week of therapy. She also had changed her deodorant from Secret Clinical Strength back to the usual Secret Original. The patient discontinued topical treatment after clearing of the lesions. Three weeks later, clinical examination revealed postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the axillae, and the prior lesions had resolved (Figure 3).

Granular parakeratosis is an unusual condition most commonly presenting in middle-aged women in the axillae, with a clinical presentation of erythematous to brownish hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques. Although few cases have been reported, granular parakeratosis likely is more common than has been reported. There have been reports involving the scalp, cheeks, abdomen, thighs, and other intertriginous areas including inguinal folds and the submammary region.1-4 There also is an infantile form related to diapers and zinc oxide paste.5 Although uncommon, granular parakeratosis can occur as a single papule or plaque and is termed granular parakeratotic acanthoma.6 Lesions may persist for months, spontaneously resolve and recur, and occasionally evolve into fissures and erosions due to irritation. Pruritus is a common concern. Histology of granular parakeratosis reveals hyperkeratosis with eosinophilic staining, compact parakeratosis with retention of basophilic keratohyalin granules, and vascular proliferation and ectasia.5

The cause is unknown but possibly related to irritation from rubbing, occlusion, sweating, or deodorants.5,7 Cases indicate a link to obesity. Hypotheses as to the etiology include the disruption of cornification. Normally, filaggrin maintains the keratohyaline granules in the stratum corneum during cornification. Therefore, the retention of keratohyaline granules in granular parakeratosis may be due to a defect in processing profilaggrin to filaggrin, which has been proposed based on ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies.8

The differential diagnosis includes granular parakeratosis, intertrigo (caused by seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, or erythrasma), Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. The papules may resemble seborrheic keratoses, while the plaques can be mistaken for acanthosis nigricans.

Therapeutic success has been reported with topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, topical or oral retinoids, ammonium lactate, calcineurin inhibitors, topical or oral antifungals, cryotherapy, and botulinum toxin injections.3,9-11 In addition, parakeratosis has decreased in biopsies from psoriatic patients after acitretin, methotrexate, and phototherapy, which may be alternative treatments for unusually difficult or recalcitrant cases of granular parakeratosis. To minimize side effects and resolve the papules quickly, we combined 2 synergistic agents—glycolic acid and tretinoin—each with different mechanisms of action, and we observed excellent clinical response.

Granular parakeratosis is possibly related to a combination of topical products that potentiate irritation, rubbing, and occlusion of sweat. Multiple treatment modalities likely contribute to clearing, the most important being removal of any triggering topical products. Our patient’s change in deodorant may have been the inciting factor for the disease. Withdrawal of the Secret Clinical Strength deodorant prompted clearing, though topical retinoid and glycolic acid acted as facilitating therapies for timely results. A thorough history, as highlighted by this case, may help pinpoint etiologic factors. By identifying a seemingly innocuous change in hygienic routine, we were able to minimize the need for ongoing therapy.

To the Editor:

A 46-year-old overweight woman presented with a rash in the axillae of 2 months’ duration. She did not report any additional symptoms such as pruritus or pain. She reported changing her deodorant recently from Secret Original to Secret Clinical Strength (both Procter & Gamble). Her medical history was remarkable for asthma and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical examination revealed erythematous-brown, stuccolike, hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques in recently shaved axillae, affecting the left axilla more than the right axilla (Figure 1). The clinical differential diagnosis included granular parakeratosis, intertrigo, Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic keratoses, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy revealed a marked compact parakeratotic horn with retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). The subjacent epidermis showed some acanthosis and spongiosis with mild chronic inflammation of the dermal rim. Based on histopathology, granular parakeratosis was diagnosed.

At a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, we prescribed glycolic acid lotion 10% applied to the axillae twice daily, plus tretinoin gel 0.05% applied to the axillae each evening. She reported clearing after 1 week of therapy. She also had changed her deodorant from Secret Clinical Strength back to the usual Secret Original. The patient discontinued topical treatment after clearing of the lesions. Three weeks later, clinical examination revealed postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the axillae, and the prior lesions had resolved (Figure 3).

Granular parakeratosis is an unusual condition most commonly presenting in middle-aged women in the axillae, with a clinical presentation of erythematous to brownish hyperkeratotic papules coalescing into plaques. Although few cases have been reported, granular parakeratosis likely is more common than has been reported. There have been reports involving the scalp, cheeks, abdomen, thighs, and other intertriginous areas including inguinal folds and the submammary region.1-4 There also is an infantile form related to diapers and zinc oxide paste.5 Although uncommon, granular parakeratosis can occur as a single papule or plaque and is termed granular parakeratotic acanthoma.6 Lesions may persist for months, spontaneously resolve and recur, and occasionally evolve into fissures and erosions due to irritation. Pruritus is a common concern. Histology of granular parakeratosis reveals hyperkeratosis with eosinophilic staining, compact parakeratosis with retention of basophilic keratohyalin granules, and vascular proliferation and ectasia.5

The cause is unknown but possibly related to irritation from rubbing, occlusion, sweating, or deodorants.5,7 Cases indicate a link to obesity. Hypotheses as to the etiology include the disruption of cornification. Normally, filaggrin maintains the keratohyaline granules in the stratum corneum during cornification. Therefore, the retention of keratohyaline granules in granular parakeratosis may be due to a defect in processing profilaggrin to filaggrin, which has been proposed based on ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies.8

The differential diagnosis includes granular parakeratosis, intertrigo (caused by seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, inverse psoriasis, or erythrasma), Hailey-Hailey disease, Darier disease, pemphigus vegetans, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, and irritant or allergic contact dermatitis. The papules may resemble seborrheic keratoses, while the plaques can be mistaken for acanthosis nigricans.

Therapeutic success has been reported with topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, topical or oral retinoids, ammonium lactate, calcineurin inhibitors, topical or oral antifungals, cryotherapy, and botulinum toxin injections.3,9-11 In addition, parakeratosis has decreased in biopsies from psoriatic patients after acitretin, methotrexate, and phototherapy, which may be alternative treatments for unusually difficult or recalcitrant cases of granular parakeratosis. To minimize side effects and resolve the papules quickly, we combined 2 synergistic agents—glycolic acid and tretinoin—each with different mechanisms of action, and we observed excellent clinical response.

Granular parakeratosis is possibly related to a combination of topical products that potentiate irritation, rubbing, and occlusion of sweat. Multiple treatment modalities likely contribute to clearing, the most important being removal of any triggering topical products. Our patient’s change in deodorant may have been the inciting factor for the disease. Withdrawal of the Secret Clinical Strength deodorant prompted clearing, though topical retinoid and glycolic acid acted as facilitating therapies for timely results. A thorough history, as highlighted by this case, may help pinpoint etiologic factors. By identifying a seemingly innocuous change in hygienic routine, we were able to minimize the need for ongoing therapy.

- Graham R. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:AB45-AB45.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Channual J, Fife DJ, Wu JJ. Axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2013;92;61, 65-66.

- Streams S, Gottwald L, Zaher A, et al. Granular parakeratosis of the scalp: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:AB81-AB81.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2015.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Granular parakeratotic acanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:393-396.

- Naylor E, Wartman D, Telang G, et al. Granular parakeratosis secondary to postsurgical occlusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB126.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2012.

- Baum B, Skopit S. Granular parakeratosis treatment with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment: a case presentation and discussion. J Am Osteo Coll Dermatol. 2013;26:40-41.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S279-S280.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:789790.

- Graham R. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:AB45-AB45.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Channual J, Fife DJ, Wu JJ. Axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2013;92;61, 65-66.

- Streams S, Gottwald L, Zaher A, et al. Granular parakeratosis of the scalp: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:AB81-AB81.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2015.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Granular parakeratotic acanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:393-396.

- Naylor E, Wartman D, Telang G, et al. Granular parakeratosis secondary to postsurgical occlusion. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:AB126.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; 2012.

- Baum B, Skopit S. Granular parakeratosis treatment with tacrolimus 0.1% ointment: a case presentation and discussion. J Am Osteo Coll Dermatol. 2013;26:40-41.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:S279-S280.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:789790.

Practice Points

- Granular parakeratosis most commonly presents in middle-aged women in the axillae.

- The cause is unknown but possibly related to irritation from rubbing, occlusion, sweating, or deodorants.

- Multiple treatment modalities likely contribute to clearing, the most important being removal of any triggering topical products.

Pustular Tinea Id Reaction

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

Practice Points

• Id reactions, or autoeczematization, can occur secondary to dermatophyte infections, possibly due to a hypersensitivity reaction to the fungus. These eruptions can occur in many forms of tinea and in a variety of clinical presentations.

• Treatment is based on clearance of the original dermatophyte infection.

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

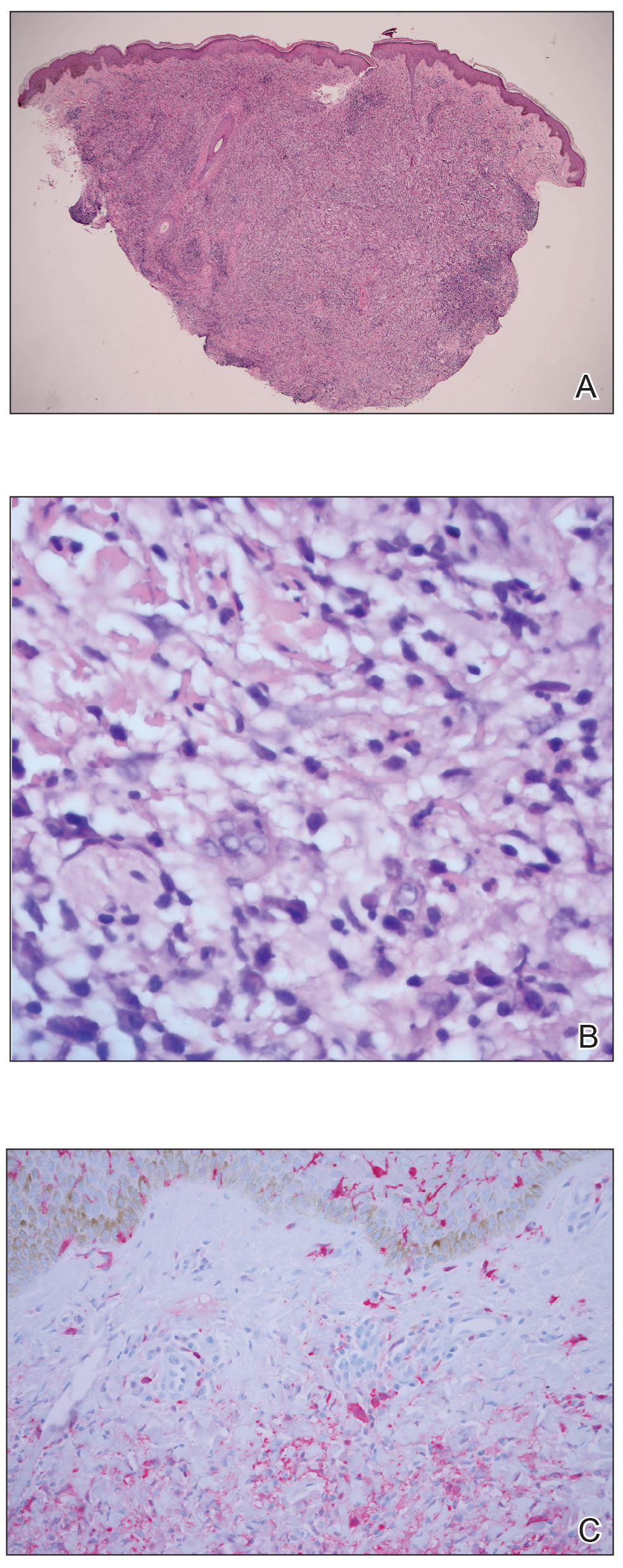

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1

The etiology of CRDD remains unknown with hypotheses of viral and immune causes such as human herpesvirus 6, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19. The polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate and the clinical progression of RDD suggest a reactive process rather than a neoplastic disorder.1 Rosai-Dorfman disease has been hypothesized to be closely related to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, an inherited disorder associated with defects in Fas-mediated apoptosis.5

Histologic findings in CRDD are similar to those in RDD, with a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diffuse and nodular dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes exists in a background infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Foamy histiocytes may be seen in dermal lymphatics, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers also may be present. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes, is common in CRDD. Less often, histiocytes may contain plasma cells, neutrophils, and red blood cells. Mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare. Cutaneous RDD histiocytes stain positive for S-100 protein, CD4, factor XIIIa, and CD68, and negative for CD1a. Birbeck granules are absent on electronic microscopy of CRDD tissue, eliminating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1,3,5

The clinical diagnosis of CRDD is hard to confirm in the absence of lymphadenopathy. The lesions in CRDD may be solitary or numerous, usually presenting as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. More rarely, the lesions may present as pustules, acneform lesions, mimickers of vasculitis and panniculitis, macular erythema, large annular lesions resembling granuloma annulare, or even a breast mass.1,3 One case report with involvement of deep subcutaneous fat presented with flank swelling beneath papules and nodules.6

The most common site of lesions in CRDD is the face, with the eyelids and malar regions frequently involved, followed by the back, chest, thighs, flanks, and shoulders.1,5 Rarely, CRDD may be associated with other disorders, including bilateral uveitis, antinuclear antibody–positive lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus.1

Numerous treatments have been attempted, yet the response often is poor. Because RDD is a benign and self-limiting disease, less aggressive therapeutic approaches should be used, if possible. Surgical excision of the lesions has been helpful in certain cases.6 Cryotherapy and local radiation, topical steroids, or laser treatment also have been found to improve the condition.1,7 For refractory cases, dapsone and thalidomide have been effective. Mixed results have been observed with isotretinoin and imatinib; some patients improved whereas others did not. Utikal et al8 described a patient with complete remission of CRDD after receiving imatinib therapy; however, a different study reported a patient with CRDD who was completely resistant to this treatment.9 One case presenting on the breast did not respond to topical steroids, acitretin, and thalidomide but later responded to methotrexate.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous RDD is an unusual clinical entity with varied lesions. Generally, CRDD follows a benign clinical course, with a possibility of spontaneous remission. Further studies are required to confidently classify the etiology and variance between both RDD and CRDD.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review [published online February 5, 2015]. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Chen A, Fernedez A, Janik M, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB48.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Thawerani H, Sanchez RL, Rosai J, et al. The cutaneous manifestations of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:191-197.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Al Salamah SM, Abdullah M, Al Salamah RA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease presenting as a flank swelling. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8:434-438.

- Khan A, Musbahi E, Suchak R, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease treated by surgical excision and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB259.

- Utikal J, Ugurel S, Kurzen H, et al. Imatinib as a treatment option forsystemic non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:736-740.

- Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Paasch V, et al. A case of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease refractory to imatinib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:571-574.

- Nadal M, Kervarrec T, Machet MC, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease located on the breast: rapid effectiveness of methotrexate after failure of topical corticosteroids, acitretin and thalidomide. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:758-759.

Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1

The etiology of CRDD remains unknown with hypotheses of viral and immune causes such as human herpesvirus 6, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19. The polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate and the clinical progression of RDD suggest a reactive process rather than a neoplastic disorder.1 Rosai-Dorfman disease has been hypothesized to be closely related to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, an inherited disorder associated with defects in Fas-mediated apoptosis.5

Histologic findings in CRDD are similar to those in RDD, with a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diffuse and nodular dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes exists in a background infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Foamy histiocytes may be seen in dermal lymphatics, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers also may be present. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes, is common in CRDD. Less often, histiocytes may contain plasma cells, neutrophils, and red blood cells. Mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare. Cutaneous RDD histiocytes stain positive for S-100 protein, CD4, factor XIIIa, and CD68, and negative for CD1a. Birbeck granules are absent on electronic microscopy of CRDD tissue, eliminating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1,3,5

The clinical diagnosis of CRDD is hard to confirm in the absence of lymphadenopathy. The lesions in CRDD may be solitary or numerous, usually presenting as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. More rarely, the lesions may present as pustules, acneform lesions, mimickers of vasculitis and panniculitis, macular erythema, large annular lesions resembling granuloma annulare, or even a breast mass.1,3 One case report with involvement of deep subcutaneous fat presented with flank swelling beneath papules and nodules.6

The most common site of lesions in CRDD is the face, with the eyelids and malar regions frequently involved, followed by the back, chest, thighs, flanks, and shoulders.1,5 Rarely, CRDD may be associated with other disorders, including bilateral uveitis, antinuclear antibody–positive lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus.1

Numerous treatments have been attempted, yet the response often is poor. Because RDD is a benign and self-limiting disease, less aggressive therapeutic approaches should be used, if possible. Surgical excision of the lesions has been helpful in certain cases.6 Cryotherapy and local radiation, topical steroids, or laser treatment also have been found to improve the condition.1,7 For refractory cases, dapsone and thalidomide have been effective. Mixed results have been observed with isotretinoin and imatinib; some patients improved whereas others did not. Utikal et al8 described a patient with complete remission of CRDD after receiving imatinib therapy; however, a different study reported a patient with CRDD who was completely resistant to this treatment.9 One case presenting on the breast did not respond to topical steroids, acitretin, and thalidomide but later responded to methotrexate.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous RDD is an unusual clinical entity with varied lesions. Generally, CRDD follows a benign clinical course, with a possibility of spontaneous remission. Further studies are required to confidently classify the etiology and variance between both RDD and CRDD.

Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1

The etiology of CRDD remains unknown with hypotheses of viral and immune causes such as human herpesvirus 6, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19. The polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate and the clinical progression of RDD suggest a reactive process rather than a neoplastic disorder.1 Rosai-Dorfman disease has been hypothesized to be closely related to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, an inherited disorder associated with defects in Fas-mediated apoptosis.5

Histologic findings in CRDD are similar to those in RDD, with a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diffuse and nodular dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes exists in a background infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Foamy histiocytes may be seen in dermal lymphatics, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers also may be present. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes, is common in CRDD. Less often, histiocytes may contain plasma cells, neutrophils, and red blood cells. Mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare. Cutaneous RDD histiocytes stain positive for S-100 protein, CD4, factor XIIIa, and CD68, and negative for CD1a. Birbeck granules are absent on electronic microscopy of CRDD tissue, eliminating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1,3,5

The clinical diagnosis of CRDD is hard to confirm in the absence of lymphadenopathy. The lesions in CRDD may be solitary or numerous, usually presenting as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. More rarely, the lesions may present as pustules, acneform lesions, mimickers of vasculitis and panniculitis, macular erythema, large annular lesions resembling granuloma annulare, or even a breast mass.1,3 One case report with involvement of deep subcutaneous fat presented with flank swelling beneath papules and nodules.6

The most common site of lesions in CRDD is the face, with the eyelids and malar regions frequently involved, followed by the back, chest, thighs, flanks, and shoulders.1,5 Rarely, CRDD may be associated with other disorders, including bilateral uveitis, antinuclear antibody–positive lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus.1

Numerous treatments have been attempted, yet the response often is poor. Because RDD is a benign and self-limiting disease, less aggressive therapeutic approaches should be used, if possible. Surgical excision of the lesions has been helpful in certain cases.6 Cryotherapy and local radiation, topical steroids, or laser treatment also have been found to improve the condition.1,7 For refractory cases, dapsone and thalidomide have been effective. Mixed results have been observed with isotretinoin and imatinib; some patients improved whereas others did not. Utikal et al8 described a patient with complete remission of CRDD after receiving imatinib therapy; however, a different study reported a patient with CRDD who was completely resistant to this treatment.9 One case presenting on the breast did not respond to topical steroids, acitretin, and thalidomide but later responded to methotrexate.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous RDD is an unusual clinical entity with varied lesions. Generally, CRDD follows a benign clinical course, with a possibility of spontaneous remission. Further studies are required to confidently classify the etiology and variance between both RDD and CRDD.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review [published online February 5, 2015]. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Chen A, Fernedez A, Janik M, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB48.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Thawerani H, Sanchez RL, Rosai J, et al. The cutaneous manifestations of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:191-197.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Al Salamah SM, Abdullah M, Al Salamah RA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease presenting as a flank swelling. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8:434-438.

- Khan A, Musbahi E, Suchak R, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease treated by surgical excision and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB259.

- Utikal J, Ugurel S, Kurzen H, et al. Imatinib as a treatment option forsystemic non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:736-740.

- Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Paasch V, et al. A case of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease refractory to imatinib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:571-574.

- Nadal M, Kervarrec T, Machet MC, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease located on the breast: rapid effectiveness of methotrexate after failure of topical corticosteroids, acitretin and thalidomide. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:758-759.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review [published online February 5, 2015]. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Chen A, Fernedez A, Janik M, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB48.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Thawerani H, Sanchez RL, Rosai J, et al. The cutaneous manifestations of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:191-197.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Al Salamah SM, Abdullah M, Al Salamah RA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease presenting as a flank swelling. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8:434-438.

- Khan A, Musbahi E, Suchak R, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease treated by surgical excision and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB259.

- Utikal J, Ugurel S, Kurzen H, et al. Imatinib as a treatment option forsystemic non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:736-740.

- Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Paasch V, et al. A case of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease refractory to imatinib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:571-574.

- Nadal M, Kervarrec T, Machet MC, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease located on the breast: rapid effectiveness of methotrexate after failure of topical corticosteroids, acitretin and thalidomide. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:758-759.

Practice Points

- Rosai-Dorfman disease generally is characterized by painless cervical lymphadenopathy and systemic involvement.

- Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease can clinically present with great variety, mimicking many other dermatologic conditions.

- Patients presenting with cutaneous lesions and lymphadenopathy warrant workup with systemic imaging.