A new mother drowned her 6-month-old daughter in the bathtub. The married woman, who had a history of schizoaffective disorder, had been high functioning and worked in a managerial role prior to giving birth. However, within a day of delivery, her mental state deteriorated. She quickly became convinced that her daughter had a genetic disorder such as achondroplasia. Physical examinations, genetic testing, and x-rays all failed to alleviate her concerns. Examination of her computer revealed thousands of searches for various medical conditions and surgical treatments. After the baby’s death, the mother was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She eventually pled guilty to manslaughter.1

Mothers with postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically present fulminantly within days to weeks of giving birth. Symptoms of PPP may include not only psychosis, but also confusion and dysphoric mania. These symptoms often wax and wane, which can make it challenging to establish the diagnosis. In addition, many mothers hide their symptoms due to poor insight, delusions, or fear of loss of custody of their infant. In the vast majority of cases, psychiatric hospitalization is required to protect both mother and baby; untreated, there is an elevated risk of both maternal suicide and infanticide. This article discusses the presentation of PPP, its differential diagnosis, risk factors for developing PPP, suicide and infanticide risk assessment, treatment (including during breastfeeding), and prevention.

The bipolar connection

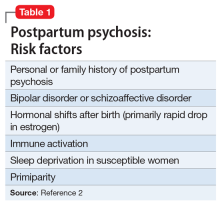

While multiple factors may increase the risk of PPP (Table 12), women with bipolar disorder have a particularly elevated risk. After experiencing incipient postpartum affective psychosis, a woman has a 50% to 80% chance of having another psychiatric episode, usually within the bipolar spectrum.2 Of all women with PPP, 70% to 90% have bipolar illness or schizoaffective disorder, while approximately 12% have schizophrenia.3,4Women with bipolar disorder are more likely to experience a postpartum psychiatric admission than mothers with any other psychiatric diagnosis5 and have an increased risk of PPP by a factor of 100 over the general population.2

For women with bipolar disorder, PPP should be understood as a recurrence of the chronic disease. Recent evidence does suggest, however, that a significant minority of women progress to experience mood and psychotic symptoms only in the postpartum period.6,7 It is hypothesized that this subgroup of women has a biologic vulnerability to affective psychosis that is limited to the postpartum period. Clinically, understanding a woman’s disease course is important because it may guide decision-making about prophylactic medications during or after pregnancy.

A rapid, delirium-like presentation

Postpartum psychosis is a rare disorder, with a prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 childbirths.3 While symptoms may begin days to weeks postpartum, the typical time of onset is between 3 to 10 days after birth, occurring after a woman has been discharged from the hospital and during a time of change and uncertainty. This can make the presentation of PPP a confusing and distressing experience for both the new mother and the family, resulting in delays in seeking care.

Subtle prodromal symptoms may include insomnia, mood fluctuation, and irritability. As symptoms progress, PPP is notable for a rapid onset and a delirium-like appearance that may include waxing and waning cognitive symptoms such as disorientation and confusion.8 Grossly disorganized behaviors and rapid mood fluctuations are typical. Distinct from mood episodes outside the peripartum period, women with PPP often experience mood-incongruent delusions and obsessive thoughts, often focused on their child.9 Women with PPP appear less likely to experience thought insertion or withdrawal or auditory hallucinations that give a running commentary.2

Differential diagnosis includes depression, OCD

When evaluating a woman with possible postpartum psychotic symptoms or delirium, it is important to include a thorough history, physical examination, and relevant laboratory and/or imaging investigations to assess for organic causes or contributors (Table 22,6,10-12 and Table 32,6,10-12). A detailed psychiatric history should establish whether the patient is presenting with new-onset psychosis or has had previous mood or psychotic episodes that may have gone undetected. Important perinatal psychiatric differential diagnoses should include “baby blues,” postpartum depression (PPD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Continue to: PPP vs "baby blues."