Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the most common congenital viral infection in U.S. children, with a frequency between 0.5% and 1% of newborn infants resulting in approximately 30,000 infected children annually. A small minority (approximately 10%) can be identified in the neonatal period as symptomatic with jaundice (from direct hyperbilirubinemia), petechiae (from thrombocytopenia), hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, or other manifestations. The vast majority are asymptomatic at birth, yet 15% will have or develop sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) during the first few years of life; others (1%-2%) will develop vision loss associated with retinal scars. Congenital CMV accounts for 20% of those with SNHL detected at birth and 25% of children with SNHL at 4 years of age.

Screening for congenital CMV has been an ongoing subject of debate. The challenges of implementing screening programs are related both to the diagnostics (collecting urine samples on newborns) as well as with the question of whether we have treatment and interventions to offer babies diagnosed with congenital CMV across the complete spectrum of clinical presentations.

Current screening programs implemented in some hospitals, called “targeted screening,” in which babies who fail newborn screening programs are tested for CMV, are not sufficient to achieve the goal of identifying babies who will need follow-up for early detection of SNHL or vision abnormalities, or possibly early antiviral therapy (Valcyte; valganciclovir), because only a small portion of those who eventually develop SNHL are currently identified by the targeted screening programs.1

However, its availability only has added to the debate as to whether the time has arrived for universal screening.

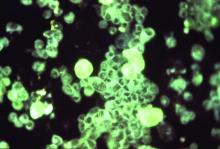

Vertical transmission of CMV occurs in utero (during any of the trimesters), at birth by passage through the birth canal, or postnatally by ingestion of breast milk. Neonatal infection (in utero and postnatal) occurs in both mothers with primary CMV infection during gestation and in those with recurrent infection (from a different viral strain) or reactivation of infection. Severe clinically symptomatic disease and sequelae is associated with primary maternal infection and early transmission to the fetus. However, it is estimated that nonprimary maternal infection accounts for 75% of neonatal infections. Transmission by breast milk to full-term, healthy infants does not appear to be associated with clinical illness or sequelae; however, preterm infants or those with birth weights less than 1,500 g have a small risk of developing clinical disease.

The polymerase chain reaction–based saliva CMV test (Alethia CMV Assay Test System) was licensed by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2018 after studies demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, compared with viral culture (the gold standard). In one study, 17,327 infants were screened with the liquid-saliva PCR assay, and 0.5% tested positive for CMV on both the saliva test and culture. Sensitivity and specificity of the liquid-saliva PCR assay were 100% and 99.9%, respectively.2 The availability of an approved saliva-based assay that is both highly sensitive and specific overcomes the challenge of collecting urine, which has been a limiting factor in development of pragmatic universal screening programs. To date, most of the focus in identification of congenital CMV infection has been linking newborn hearing testing programs with CMV testing. For some, these have been labeled “targeted screening programs for CMV.” To us, these appear to be best practice for medical evaluations of an infant with identified SNHL. The availability of saliva-based CMV testing should enable virtually all children who fail newborn screening to be tested for CMV. In multiple studies,3,4 6% of infants with confirmed hearing screen failure tested positive for CMV. A recent study5 identified only 1 infant among the 171 infants who failed newborn screening, however only approximately 15% of the infants were eventually confirmed as hearing impaired at audiology follow-up, suggesting that programmatically testing for CMV might be limited to those with confirmed hearing loss if such can be accomplished within a narrow window of time.