Psoriasis is a systemic immune-mediated disorder characterized by erythematous, scaly, well-demarcated plaques on the skin that affects approximately 3% of the world’s population.1 The disease is moderate to severe for approximately 1 in 6 individuals with psoriasis.2 These patients, particularly those with symptoms that are refractory to topical therapy and/or phototherapy, can benefit from the use of biologic agents, which are monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins engineered to inhibit the action of cytokines that drive psoriatic inflammation.

In February 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released an updated set of guidelines for the use of biologics in treating adult patients with psoriasis.3 The prior guidelines were released in 2008 when just 3 biologics—etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab—were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the management of psoriasis. These older recommendations were mostly based on studies of the efficacy and safety of biologics for patients with psoriatic arthritis.4 Over the last 11 years, 8 novel biologics have gained FDA approval, and numerous large phase 2 and phase 3 trials evaluating the risks and benefits of biologics have been conducted. The new guidelines contain considerably more detail and are based on evidence more specific to psoriasis rather than to psoriatic arthritis. Given the large repertoire of biologics available today and the increased amount of published research regarding each one, these guidelines may aid dermatologists in choosing the optimal biologic and managing therapy.

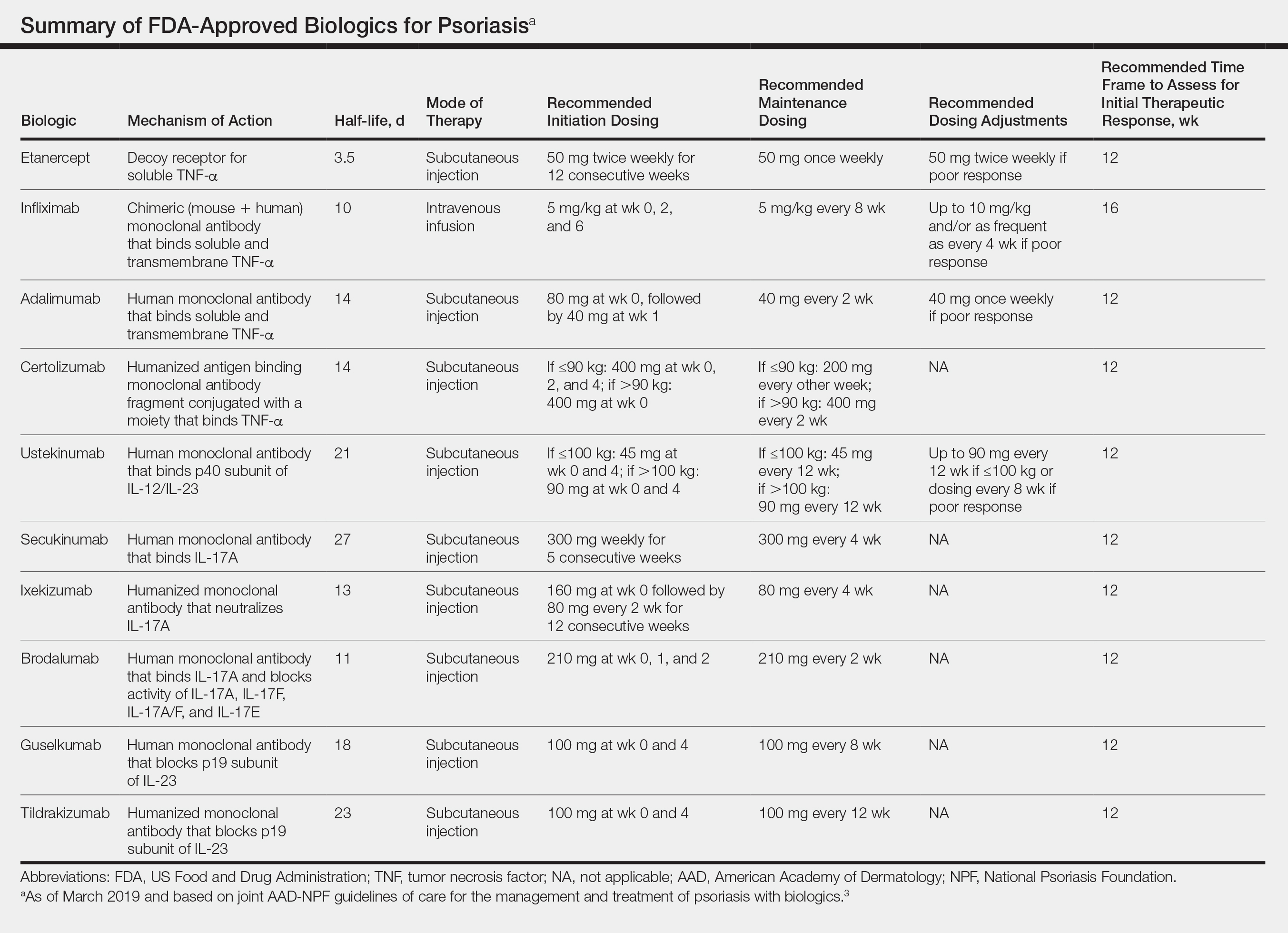

The AAD-NPF recommendations discuss the mechanism of action, efficacy, safety, and adverse events of the 10 biologics that have been FDA approved for the treatment of psoriasis as of March 2019, plus risankizumab, which was pending FDA approval at the time of publication and was later approved in April 2019. They also address dosing regimens, potential to combine biologics with other therapies, and different forms of psoriasis for which each may be effective.3 The purpose of this discussion is to present these guidelines in a condensed form to prescribers of biologic therapies and review the most clinically significant considerations during each step of treatment. Of note, we highlight only treatment of adult patients and do not discuss information relevant to risankizumab, as it was not FDA approved when the AAD-NPF guidelines were released.

Choosing a Biologic

Biologic therapy may be considered for patients with psoriasis that affects more than 3% of the body’s surface and is recalcitrant to localized therapies. There is no particular first-line biologic recommended for all patients with psoriasis; rather, choice of therapy should be individualized to the patient, considering factors such as body parts affected, comorbidities, lifestyle, and drug cost.

All 10 FDA-approved biologics (Table) have been ranked by the AAD and NPF as having grade A evidence for efficacy as monotherapy in the treatment of moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis. Involvement of difficult-to-treat areas may be considered when choosing a specific therapy. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors etanercept and adalimumab, the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab, and the IL-23 inhibitor guselkumab have the greatest evidence for efficacy in treatment of nail disease. For scalp involvement, etanercept and guselkumab have the highest-quality evidence, and for palmoplantar disease, adalimumab, secukinumab, and guselkumab are considered the most effective. The TNF-α inhibitors are considered the optimal treatment option for concurrent psoriatic arthritis, though the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab and the IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab also have shown grade A evidence of efficacy. Of note, because TNF-α inhibitors received the earliest FDA approval, there is most evidence available for this class. Therapies with lower evidence quality for certain forms of psoriasis may show real-world effectiveness in individual patients, though more trials will be necessary to generate a body of evidence to change these clinical recommendations.

In pregnant women or those are anticipating pregnancy, certolizumab may be considered, as it is the only biologic shown to have minimal to no placental transfer. Other TNF-α inhibitors may undergo active placental transfer, particularly during the latter half of pregnancy,5 and the greatest theoretical risk of transfer occurs in the third trimester. Although these drugs may not directly harm the fetus, they do cause fetal immunosuppression for up to the first 3 months of life. All TNF-α inhibitors are considered safe during lactation. There are inadequate data regarding the safety of other classes of biologics during pregnancy and lactation.