The sexually transmitted disease (STD) epidemic in the United States is intensifying, and it disproportionately impacts high-risk communities. In 2018, rates of reportable STDs, including syphilis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections, reached an all-time high.1 That year, there were 1.8 million cases of chlamydia (increased 19% since 2014), 583,405 cases of gonorrhea (increased 63% since 2014), and 35,063 cases of primary and secondary syphilis (71% increase from 2014).1

Cases of newborn syphilis have more than doubled in 4 years, with rates reaching a 20-year high.1

This surge has not received the attention it deserves given the broad-reaching impact of these infections on women’s health and maternal-child health.2 As ObGyns, we are on the front line, and we need to be engaged in evidence-based strategies and population-based health initiatives to expedite diagnoses and treatment and to reduce the ongoing spread of these infections.

Disparities exist and continue to fuel this epidemic

The STD burden is disproportionately high among reproductive-aged women, and half of all reported STDs occur in women aged 15 to 24 years. African American women have rates up to 12 times higher than white women.3,4 Substantial geographic variability also exists, with the South, Southeast, and West having some of the highest STD rates.

These disparities are fueled by inequalities in socioeconomic status (SES), including employment, insurance, education, incarceration, stress/trauma exposure, and discrimination.5-7 Those with lower SES often have trouble accessing and affording quality health care, including sexual health services. Access to quality health care, including STD prevention and treatment, that meets the needs of lower SES populations is key to reducing STD disparities in the United States; however, access likely will be insufficient unless the structural inequities that drive these disparities are addressed.

Clinical consequences for women, infants, and mothers

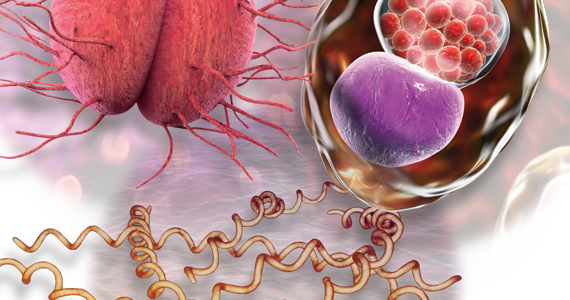

STDs are most prevalent among reproductive-aged women and can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy,4,8 and increased risk of acquiring human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). STDs during pregnancy present additional consequences. Congenital syphilis is perhaps the most salient, with neonates experiencing substantial disability or death.

In addition, STDs contribute to overall peripartum and long-term adverse health outcomes.4,9,10 Untreated chlamydia infection, for example, is associated with neonatal pneumonia, neonatal conjunctivitis, low birth weight, premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and postpartum endometritis.2,11 Untreated gonorrhea is linked to disseminated gonococcal infection in the newborn, neonatal conjunctivitis, low birth weight, miscarriage, premature rupture of membranes, preterm labor, and chorioamnionitis.2,12

As preterm birth is the leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality and disproportionately affects African American women and women in the southeastern United States,13 there is a critical public heath need to improve STD screening, treatment, and prevention of reinfection among high-risk pregnant women.

Quality clinical services for STDs: Areas for focus

More and more, STDs are being diagnosed in primary care settings. In January 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a document, referred to as STD QCS (quality clinical services), that outlines recommendations for basic and specialty-level STD clinical services.14 ObGyns and other clinicians who provide primary care should meet the basic recommendations as a minimum.

The STD QCS outlines 8 recommendation areas: sexual history and physical examination, prevention, screening, partner services, evaluation of STD-related conditions, laboratory, treatment, and referral to a specialist for complex STD or STD-related conditions.14 These recommendations can be used by providers, managers, advocates, and others working to implement the highest-quality STD clinical services. Below are key areas that can be addressed in ObGyn practice.

Continue to: Sexual history and physical examination...