An antiseizure medication appears to reduce anhedonia in patients with depression via a novel mechanism that may offer a new therapeutic target for the disorder, new research suggests.

Results of a small, randomized trial show those who received ezogabine (Potiga) experienced a significant reduction in key measures of depression and anhedonia versus placebo.

Participants in the treatment group also showed a trend toward increased response to reward anticipation on functional MRI (fMRI), compared with those treated with placebo, although the effect did not reach statistical significance.

“Our study was the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial to show that a drug affecting this kind of ion channel in the brain can improve depression and anhedonia in patients,” senior investigator James Murrough, MD, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in a press release.

“Targeting this channel represents a completely different mechanism of action than any currently available antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Murrough, who is also director of the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment at Mount Sinai.

The study was published online March 3 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Need for a novel target

“One of the main issues in treating depression is that many of our current antidepressants have similar mechanisms of action,” Dr. Murrough said in an interview. “Once a patient hasn’t responded to currently available agents, it’s hard think of new medications to fill that need.”

This need for a novel target motivated Dr. Murrough and associates to research the KCNQ2/3 potassium channel, which has not been previously studied as a therapeutic target for depression.

The KCNQ2/3 channel controls brain cell excitability and function by controlling the flow of the electrical charge across the cell membrane in the form of potassium ions, Dr. Murrough explained.

Previous research using a chronic social defeat model of depression in mice showed changes in the KCNQ2/3 channel. “This was key to determining whether a mouse showed depressive behavior in the context of stress, or whether the mice were resistant or resilient to stress,” he said.

Mice resistant to stress showed increased markers in brain regions associated with reward, while the less resilient mice showed excessive excitability and dysfunction. Dysfunction in the brain’s reward system leads to anhedonia, a “core feature” of depressive disorders.

This inspired Dr. Murrough’s group to identify ezogabine, a drug that acts on this channel.

“ for addressing depressive symptoms,” Dr. Murrough said

Nonsignificant trend

The researchers studied 45 adults diagnosed with depression who exhibited significant anhedonia and at least moderate illness severity.

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either ezogabine (n = 21, mean age 44 years at enrollment, 28.3% male) or placebo (n = 24, mean age 39 years at enrollment, 50% male). At baseline and following treatment, participants completed the incentive flanker test under fMRI conditions to model brain activity during anticipation of a reward. In addition, clinical measures of depression and anhedonia were assessed at weekly visits.

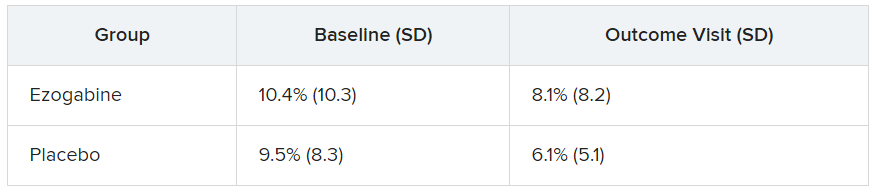

The study groups did not differ significantly in performance accuracy during the fMRI task at baseline or following treatment. The table below summarizes the percentage of errors in each group, with standard deviation.

Participants in the ezogabine group showed a numerical increase in ventral striatum activation in response to reward anticipation, compared with participants in the placebo group, but this trend was not considered significant.