For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

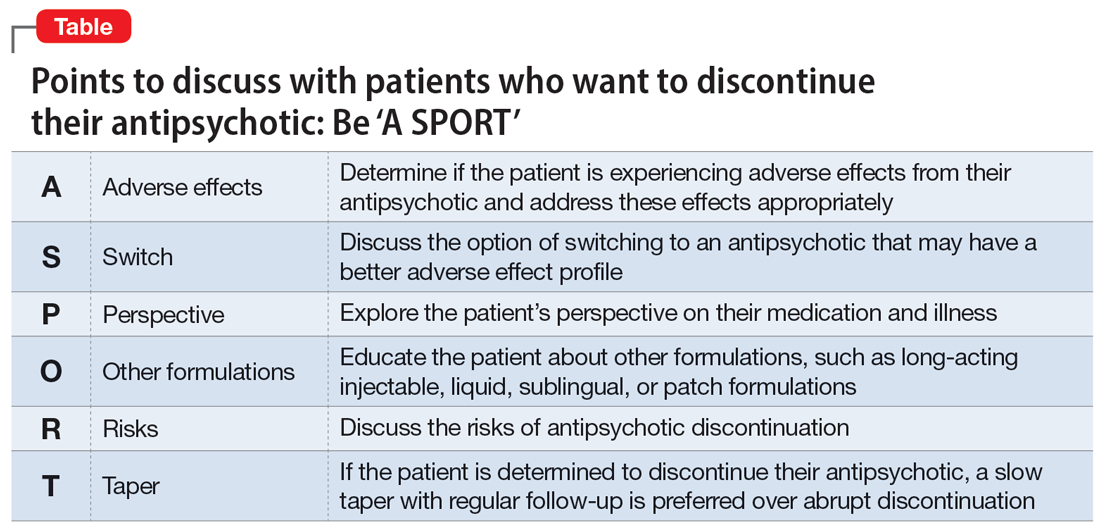

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6