The Diagnosis: Eosinophilic Fasciitis (Shulman Syndrome)

In 1984, Shulman1 reported 2 cases of diffuse fasciitis with hypergammaglobulinemia and eosinophilia, which was later termed eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) by Rodnan et al.2 Eosinophilic fasciitis also is commonly known as diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia3 or Shulman syndrome.3,4 It is an inflammatory condition of unknown etiology and pathogenesis, though an underlying autoimmune process has been proposed.3,5 The disorder is characterized by inflammation and subsequent fibrosis of deep fascia2 with variable involvement of the underlying muscle. It often is referred to as a sclerodermalike condition2,5-8 and is considered to be one of a group of fibrosing connective tissue disorders that may be confused with systemic sclerosis.3,4,6,9 Although the cause of EF is unknown, more than 50% of cases are associated with vigorous exercise or trauma.3 Other reported triggers and associations include Borrelia burgdorferi infection,5,6,10 arthropod bites,5,10 lymphoproliferative and hematologic disorders,5,6,10 inflammatory arthritis,6 morphea,3 thyroid dysfunction,5,6,10 statins,5,10 and phenytoin.5,10

There have been more than 250 cases of EF reported in the literature.3 Some authors report more frequent occurrence in males,3,4 while others report equal occurrence of disease in both males and females.5,10 Eosinophilic fasciitis has the highest incidence during the second to sixth decades of life,3,10 though childhood cases have been reported.3,11 White individuals appear to be affected most often, but sporadic cases in other ethnic groups also have been reported.3

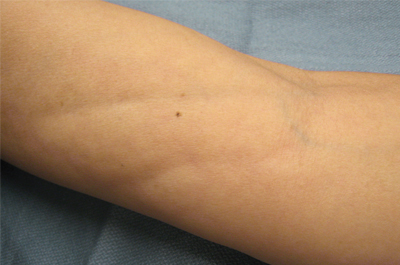

The clinical presentation of EF frequently is characterized by the rapid onset of erythema, pain, and nonpitting edema of the involved areas.5,7,10,11 Fatigue and itching also are reported symptoms.12 A cobblestone texture of the skin may be noted, commonly referred to as the peau d’orange effect.6,10 Woody induration subsequently develops, which may lead to contracture or limited range of motion.5,7,11-13 The distal extremities, particularly the forearms and calves, are the most common areas affected by EF.3 There usually is symmetric involvement; however, unilateral cases of EF also have been reported.3,6,10 Linear indentations may form along the vasculature of the involved areas when the extremities are lifted or extended. These indentations serve to demarcate the underlying muscle groups, forming the groove sign or venous furrowing.3,5,14 The epidermis is not characteristically involved in EF and wrinkling of the skin can be elicited by pinching,3 which may be helpful in clinically distinguishing EF from scleroderma. Sparing of the digits is another characteristic feature of adult-onset EF.3,10 However, involvement of the digits resulting in painless contracture has been reported in multiple childhood cases and may represent a phenotype specific to children.11 Involvement of the trunk is less frequently observed but may serve as a poor prognostic indicator; indeed, patients demonstrating young age of onset, morphealike skin sclerosis, and trunk involvement are more likely to develop refractory disease.15

Eosinophilic fasciitis is characterized by various laboratory abnormalities. Peripheral eosinophilia, hypergammaglobulinemia, elevated sedimentation rate,3,6,9,10,13,15 and elevated C-reactive protein3,6 are commonly reported; however, antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, or antibodies associated with systemic sclerosis are not frequently found.3,6 There are no laboratory abnormalities required to render a diagnosis of EF, and absence of peripheral eosinophilia has been noted in up to 20% of cases.3,4 An elevation of creatine kinase or aldolase levels may be present if muscle is involved.3,6 In general, abnormal laboratory findings have not been found to correlate with disease activity13,15 and do not appear to have prognostic significance.15

Biopsy of involved tissue characteristically reveals fascial thickening and fibrosis.10,13,15 A lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate normally is found in the subcutaneous tissues and fascia and may extend to involve the deeper dermis15 but usually spares the epidermis.3 It is important to note that increased numbers of eosinophils are not always found in the affected fascia, especially in the later stages of the disease and after steroid treatment.3,15 Muscle involvement is variable. When muscle is involved, histologic features range from mild inflammation with no evidence of necrosis3 to substantial fibrinoid necrosis.13

Magnetic resonance imaging has become a valuable tool in the diagnosis and treatment of EF. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in EF patients typically reveal fascial thickening on T1-weighted images, enhancement after the use of contrast, and hyperintensity on T2-weighted images.7 Magnetic resonance imaging has proven useful in supporting clinical diagnosis, monitoring disease activity, identifying optimal biopsy location, and determining response to treatment.3,7,8,11,13 Magnetic resonance imaging also has been proven to be particularly useful with atypical clinical presentations.8 Although deep tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis,13 magnetic resonance imaging may provide equal or superior diagnostic information.

In general, the prognosis is very good, and the majority of patients will achieve complete remission and cure.3 Up to one-third of patients with EF may experience spontaneous remission without any treatment intervention.10 The condition generally is highly responsive to oral corticosteroids,6,10,15 and it has been reported that up to 70% of patients will respond to corticosteroid treatment.3 Most patients respond to a daily dose of prednisone (0.5–1.5 mg/kg), which is continued until clinical response is observed and then followed by a slow steroid taper over a period of several months.3 Patients with persistent fibrosis often require adjunctive therapy in addition to corticosteroids. A variety of adjunctive therapies have been reported to be effective, including hydroxychloroquine sulfate,5,10,13,15,16 azathioprine,15,16 ibuprofen,10,15 D-penicillamine,5,15 cyclophosphomide,15 methotrexate,6,13,15 cyclosporine,13,15 psoralen plus UVA,5,6,15 extracorporeal photochemotherapy,5,6,10,16 colchicine,5 cimetidine,5,6,10,16 infliximab,5,6 griseofulvin,16 ketotifen,16 sulfasalazine,13 and dapsone.16 Physical therapy has been reported to be useful in preventing permanent joint contractures.3,5,10,13,16 If treatment fails, the possibility of underlying malignancy must be considered3; however, long courses of treatment are not uncommon. Some patients may need 12 to 18 months of treatment for full response, and even refractory cases are likely to eventually achieve full remission.3