Clinical Review

Zika virus: Counseling considerations for this emerging perinatal threat

Zika virus infection, although typically mild and often asymptomatic, can have serious consequences in pregnancy. As the pandemic rapidly spreads...

Anushka Chelliah, MD, and Patrick Duff, MD

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

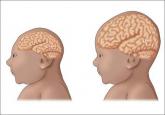

How certain can we be that the anomalies present in the case patient’s baby were caused by ZV? In the past, and for many years, scientists relied on Koch’s 4 postulates (TABLE 1) to answer this question and establish a causal relationship between a microorganism and a specific clinical disease.5 Koch’s postulates have not been satisfied for the relationship between maternal ZV infection and congenital anomalies. Today’s more relevant standards for determining causality of a teratogen were published in 1994 by Shepard.6 In 2016, Rasmussen and colleagues7 found that the critical components of these criteria are fulfilled and concluded that there is little doubt ZV is a proven and extremely dangerous teratogen. See “Zika virus has been shown to be a direct cause of microcephaly”.

Rasmussen and colleagues7 also used Hill’s criteria to assess the evidence for causation. Hill’s systematic assessment is based on 9 factors (TABLE 2)8, and Rasmussen and colleagues7 concluded that the necessary 7 of these 9 criteria have been met (the experimental animal model criterion was not satisfied, and the biological gradient criterion was not applicable). Given their assessment of Shepard’s criteria,6 the authors argued that the link between maternal ZV infection and severe congenital anomalies has risen from association to well-defined causation.

After our first review was published in March 2016,1 the testing algorithm recommended by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was revised.9 Now, according to the CDC, if a patient has had symptoms of ZV infection for less than 5 days, serum and urine should be obtained for reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing. If symptoms have been present for 5 to 14 days, urine should be tested by RT-PCR because urine samples appear to remain positive for virus longer than serum samples do. If RT-PCR is performed within the appropriate period and the result is negative, ZV infection is excluded; if the result is positive, acute ZV infection is confirmed, and additional testing is not indicated. RT-PCR can be performed by 2 commercial laboratories (Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp), state health departments, and the CDC.

If serum or urine is collected more than 5 days after symptom onset and the RT-PCR result is negative, the patient should have an immunoglobulin M (IgM) assay for ZV. If the assay result is negative, infection is excluded; if the result is positive or equivocal, additional testing is needed to ensure that the presence of the antibody does not reflect a cross-reaction to dengue or chikungunya virus. The confirmatory plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) is performed only by the CDC. To be considered positive, the PRNT result must be at least 4-fold higher than the dengue virus neutralizing antibody titer.

In patients with suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), RT-PCR can be performed on cerebrospinal fluid. For suspected fetal or neonatal infection, RT-PCR can be performed on amniotic fluid, umbilical cord blood, and fetal and placental tissue.

ZV infection has been associated with serious neurologic complications in adults. Investigators in several countries have reported dramatic increases in GBS cases during the ZV outbreak.10

GBS is an acute, immune-mediated, demyelinating peripheral neuropathy that can vary in presentation but most commonly manifests as a rapidly ascending paralysis. The disorder often is preceded by an immunization or live viral infection. In some patients, paralysis severely weakens the respiratory muscles and even the cranial nerves, and affected individuals may require intubation, ventilator support, and parenteral or enteral alimentation.

In a case-control study conducted duringthe 2013–2014 outbreak in French Polynesia, the association between ZV infection and GBS was evaluated in 3 groups of patients: 42 patients with GBS, 98 control patients, and 70 patients with ZV infection but no neurologic complications.11 Symptoms of ZV infection were present in about 88% of the patients with GBS, and the median interval from viral infection to onset of neurologic symptoms was 6 days. The ZV IgM assay was positive in 93% of GBS cases. Nerve conduction study results were consistent with the acute motor axonal neuropathy of GBS. All patients were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin; 38% of patients had to be admitted to the intensive care unit, and 29% needed respiratory support. There were no fatalities. The overall incidence of GBS was 2.4 cases per 10,000 ZV infections.

Other neurologic complications that have been associated with ZV infection are meningoencephalitis,12 brain ischemia,13 and myelitis.14

Bottom line. ZV infection may cause serious neurologic complications in adults. The most devastating complication is GBS, which can result in respiratory muscle paralysis and cranial nerve palsies.

Zika virus infection, although typically mild and often asymptomatic, can have serious consequences in pregnancy. As the pandemic rapidly spreads...

Physicians have requested information about which insect repellents to recommend to help pregnant women avoid Zika and other mosquito-born...

Recent studies offer new data on treatments for surgical-site infections after cesarean delivery, postpartum endometritis, and chlamydia infection...

Which infections affect women more adversely during pregnancy, and how can risk of exposure to these infections be diminished?