Technique for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal

Johal T, Kuruba N, Sule M, et al. Laparoscopic salpingectomy and removal of Essure hysteroscopic sterilisation device: a case series. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23(3):227-230.

Lazorwitz A, Tocce K. A case series of removal of nickel-titanium sterilization microinserts from the uterine cornua using laparoscopic electrocautery for salpingectomy. Contraception. 2017;96(2):96-98.

As reports of complications and concerns with hysteroscopic permanent contraception increase, there has been a rise in device removal procedures. We present 2 recent articles that review laparoscopic techniques for the removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraception devices and describe subsequent outcomes.

Laparoscopic salpingectomy without insert transection

In this descriptive retrospective study, Johal and colleagues reviewed hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 8 women between 2015 and 2017. The authors described their laparoscopic salpingectomy approach and perioperative complications. Overall safety and feasibility with laparoscopic salpingectomy were evaluated by identifying the number of procedures requiring intraoperative conversion to laparotomy, cornuectomy, or hysterectomy. The authors also measured operative time, estimated blood loss, length of stay, and incidence of implant fracture.

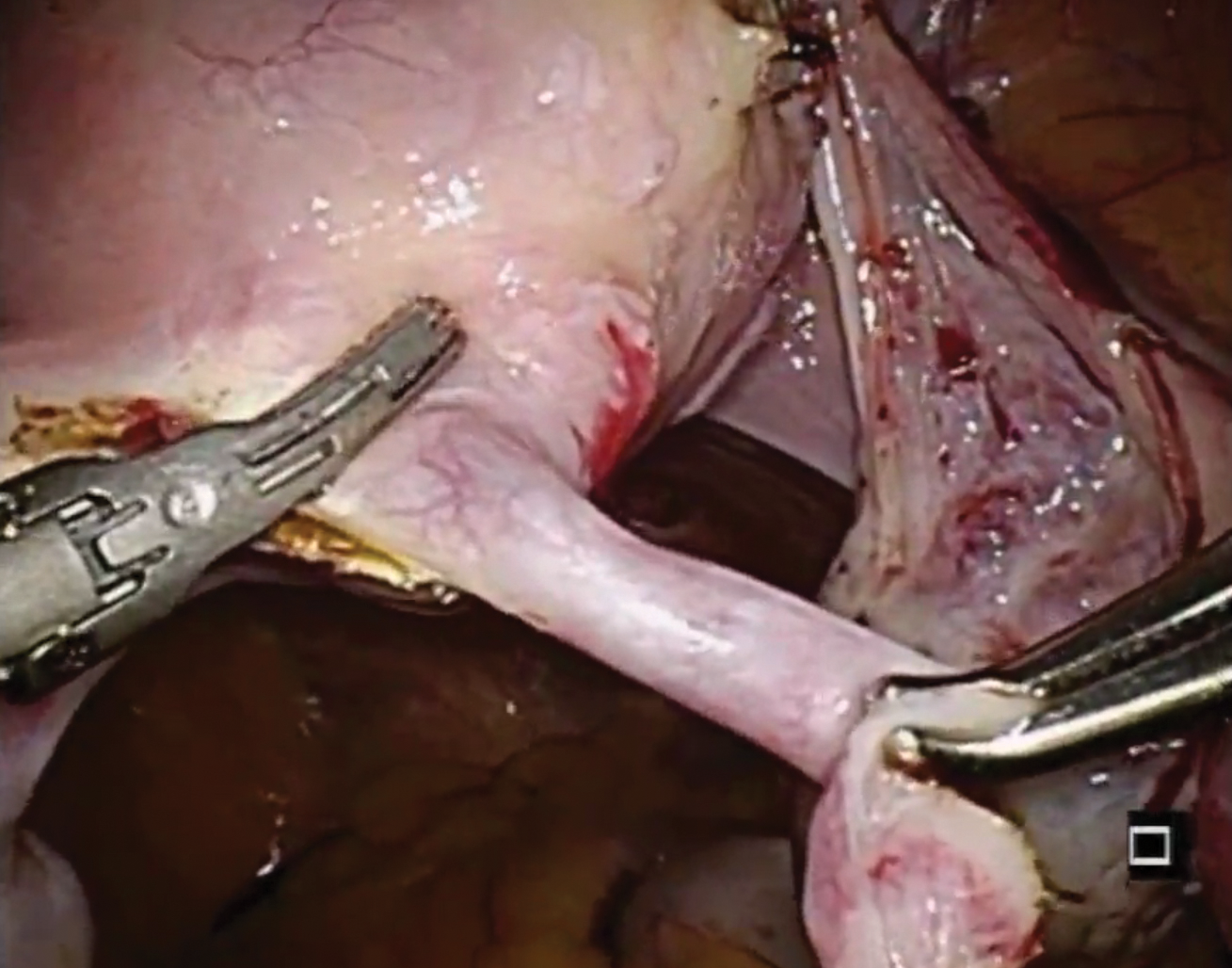

Indications for insert removal included pain (n = 4), dyspareunia (n = 2), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 4). The surgeons divided the mesosalpinx and then transected the fallopian tube approximately 1 cm distal to the cornua exposing the permanent contraception insert while avoiding direct electrosurgical application to the insert. The inserts were then removed intact with gentle traction. All 8 women underwent laparoscopic removal with salpingectomy. One patient had a surgical complication of serosal bowel injury due to laparoscopic entry that was repaired in the usual fashion. Operative time averaged 65 minutes (range, 30 to 100 minutes), blood loss was minimal, and there were no implant fractures.

Laparoscopic salpingectomy with insert transection

In this case series, Lazorwitz and Tocce described the use of laparoscopic salpingectomy for hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert removal in 20 women between 2011 and 2017. The authors described their surgical technique, which included division of the mesosalpinx followed by transection of the fallopian tube about 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the cornua. This process often resulted in transection of the insert, and the remaining insert was grasped and removed with gentle traction. If removal of the insert was incomplete, hysteroscopy was performed to identify remaining parts.

Indications for removal included pelvic pain (n = 14), abnormal uterine bleeding (n = 2), rash (n = 1), and unsuccessful placement or evidence of tubal occlusion failure during confirmatory imaging (n = 6). Three women underwent additional diagnostic hysteroscopy for retained implant fragments after laparoscopic salpingectomy. Fragments in all 3 women were 1 to 3 mm in size and left in situ as they were unable to be removed or located hysteroscopically. There were no reported postoperative complications including injury, infection, or readmission within 30 days of salpingectomy.

Shift in method use

Hysteroscopic permanent contraception procedures have low immediate surgical and medical complication rates but result in a high rate of reoperation to achieve the desired outcome. Notably, the largest available comparative trials are from Europe, which may affect the generalizability to US providers, patients, and health care systems.

Importantly, since the introduction of hysteroscopic permanent contraception in 2002, the landscape of contraception has changed in the United States. Contraception use has shifted to fewer permanent procedures and more high-efficacy reversible options. Overall, reliance on female permanent contraception has been declining in the United States, accounting for 17.8% of contracepting women in 1995 and 15.5% in 2013.27,28 Permanent contraception has begun shifting from tubal interruption to salpingectomy as mounting evidence has demonstrated up to a 65% reduction in a woman's lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.29-32 A recent study from a large Northern California integrated health system reported an increase in salpingectomy for permanent contraception from 1% of interval procedures in 2011 to 78% in 2016.33

Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods are also becoming more prevalent and are used by 7.2% of women using contraception in the United States.28,34 Typical use pregnancy rates with the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system, etonogestrel implant, and copper T380A intrauterine device are 0.2%, 0.2%, and 0.4% in the first year, respectively.35,37 These rates are about the same as those reported for Essure in the articles presented here.13,26 Because these methods are easily placed in the office and are immediately effective, their increased availability over the past decade changes demand for a permanent contraceptive procedure.

Essure underwent expedited FDA review because it had the potential to fill a contraceptive void--it was considered permanent, highly efficacious, low risk, and accessible to women regardless of health comorbidities or access to hospital operating rooms. The removal of Essure from the market is not only the result of a collection of problem reports (relatively small given the overall number of women who have used the device) but also the aggregate result of a changing marketplace and the differential needs of pharmaceutical companies and patients.

For a hysteroscopic permanent contraception insert to survive as a marketed product, the company needs high volume use. However, the increase in LARC provision and permanent contraceptive procedures using opportunistic salpingectomy have matured the market away from the presently available hysteroscopic method. This technology, in its current form, is ideal for women desiring permanent contraception but who have a contraindication to laparoscopic surgery, or for women who can access an office procedure in their community but lack access to a hospital-based procedure. For a pharmaceutical company, that smaller market may not be enough. However, the technology itself is still vital, and future development should focus on what we have learned; the ideal product should be immediately effective, not require a follow-up confirmation test, and not leave permanent foreign body within the uterus or tube.

Although both case series were small in sample size, they demonstrated the feasibility of laparoscopic removal of hysteroscopic permanent contraceptive implants. These papers described techniques that can likely be performed by individuals with appropriate laparoscopic skill and experience. The indication for most removals in these reports was pain, unsuccessful placement, or the inability to confirm tubal occlusion by imaging. Importantly, most women do not have these issues, and for those who have been using it successfully, removal is not indicated.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.