CASE Pregnant woman with abnormal vaginal discharge

A 26-year-old woman (G2P1001) at 24 weeks of gestation requests evaluation for increased frothy, whitish-gray vaginal discharge with a fishy odor. She notes that her underclothes constantly feel damp. The vaginal pH is 4.5, and the amine test is positive.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What obstetrical complications may be associated with this condition?

- How should her condition be treated?

Meet our perpetrator

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most common conditions associated with vaginal discharge among women of reproductive age. It is characterized by a polymicrobial alteration of the vaginal microbiome, and most distinctly, a relative absence of vaginal lactobacilli. This review discusses the microbiology, epidemiology, specific obstetric and gynecologic complications, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of BV.

The role of vaginal flora

Estrogen has a fundamental role in regulating the normal state of the vagina. In a woman’s reproductive years, estrogen increases glycogen in the vaginal epithelial cells, and the increased glycogen concentration promotes colonization by lactobacilli. The lack of estrogen in pre- and postmenopausal women inhibits the growth of the vaginal lactobacilli, leading to a high vaginal pH, which facilitates the growth of bacteria, particularly anaerobes, that can cause BV.

The vaginal microbiome is polymicrobial and has been classified into at least 5 community state types (CSTs). Four CSTs are dominated by lactobacilli. A fifth CST is characterized by the absence of lactobacilli and high concentrations of obligate or facultative anaerobes.1 The hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli predominate in normal vaginal flora and make up 70% to 90% of the total microbiome. These hydrogen peroxide–producing lactobacilli are associated with reduced vaginal proinflammatory cytokines and a highly acidic vaginal pH. Both factors defend against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).2

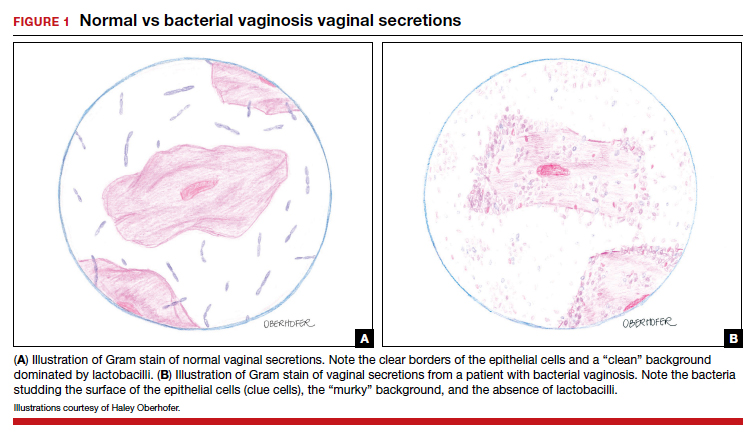

BV is a polymicrobial disorder marked by the significant reduction in the number of vaginal lactobacilli (FIGURE 1). A recent study showed that BV is associated first with a decrease in Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.3 The polymicrobial load is increased by a factor of up to 1,000, compared with normal vaginal flora.4 BV should be considered a biofilm infection caused by adherence of G vaginalis to the vaginal epithelium.5 This biofilm creates a favorable environment for the overgrowth of obligate anaerobic bacteria.

BMI factors into epidemiology

BV is the leading cause of vaginal discharge in reproductive-age women. In the United States, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimated a prevalence of 29% in the general population and 50% in Black women aged 14 to 49 years.6 In 2013, Kenyon and colleagues performed a systematic review to assess the worldwide epidemiology of BV, and the prevalence varied by country. Within the US population, rates were highest among non-Hispanic, Black women.7 Brookheart and colleagues demonstrated that, even after controlling for race, overweight and obese women had a higher frequency of BV compared with leaner women. In this investigation, the overall prevalence of BV was 28.1%. When categorized by body mass index (BMI), the prevalence was 21.3% in lean women, 30.4% in overweight women, and 34.5% in obese women (P<.001). The authors also found that Black women had a higher prevalence, independent of BMI, compared with White women.8

Complications may occur. BV is notable for having several serious sequelae in both pregnant and nonpregnant women. For obstetric patients, these sequelae include an increased risk of preterm birth; first trimester spontaneous abortion, particularly in the setting of in vitro fertilization; intra-amniotic infection; and endometritis.9,10 The risk of preterm birth increases by a factor of 2 in infected women; however, most women with BV do not deliver preterm.4 The risk of endometritis is increased 6-fold in women with BV.11 Nonpregnant women with BV are at increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative infections, and an increased susceptibility to STIs such as chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and HIV.12-15 The risk for vaginal-cuff cellulitis and abscess after hysterectomy is increased 6-fold in the setting of BV.16

Continue to: Clinical manifestations...