The prevalence of T2DM is on the rise in the United States, and T2DM is currently the 7th leading cause of death.1 In a study of 28,143 participants in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) who were 18 years or older, the prevalence of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 14.3% between 2000 and 2008.2 About 24% of the participants had undiagnosed diabetes prior to the testing they received as a study participant.2 People from minority groups have a higher rate of T2DM than non-Hispanic White people. Using data from 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes was highest among American Indians/Alaska Natives (14.7%), people of Hispanic origin (12.5%), and non-Hispanic Blacks (11.7%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (9.2%) and non-Hispanic Whites (7.5%).1 Diabetes is a major risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, renal failure, retinopathy, peripheral vascular disease, and neuropathy.1 Early detection and treatment of both prediabetes and diabetes may improve health and reduce these preventable complications, saving lives, preventing heart and renal failure and blindness.

T2DM is caused by a combination of insulin resistance and insufficient pancreatic secretion of insulin to overcome the insulin resistance.3 In young adults with insulin resistance, pancreatic secretion of insulin is often sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance resulting in normal glucose levels and persistently increased insulin concentration. As individuals with insulin resistance age, pancreatic secretion of insulin may decline, resulting in insufficient production of insulin and rising glucose levels. Many individuals experience a prolonged stage of prediabetes that may be present for decades prior to transitioning to T2DM. In 2020, 35% of US adults were reported to have prediabetes.1

Screening for diabetes mellitus

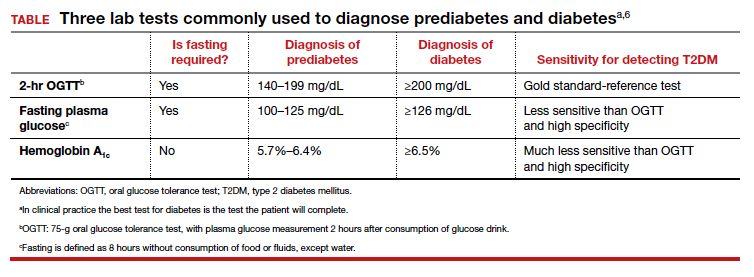

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently recommended that all adults aged 35 to 70 years who are overweight or obese be screened for T2DM (B recommendation).4 Screening for diabetes will also result in detecting many people with prediabetes. The criteria for diagnosing diabetes and prediabetes are presented in the TABLE. Based on cohort studies, the USPSTF noted that screening every 3 years is a reasonable approach.4 They also recommended that people diagnosed with prediabetes should initiate preventive measures, including optimizing diet, weight loss, exercise, and in some cases, medication treatment such as metformin.5

Approaches to the diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes

Three laboratory tests are widely utilized for the diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes: measurement of a plasma glucose 2 hours following consumption of oral glucose 75 g (2-hr oral glucose tolerance test [OGTT]), measurement of a fasting plasma glucose, and measurement of hemoglobin A1c (see Table).6In clinical practice, the best diabetes screening test is the test the patient will complete. Most evidence indicates that, compared with the 2-hr OGTT, a hemoglobin A1c measurement is specific for diagnosing T2DM, but not sensitive. In other words, if the hemoglobin A1c is ≥6.5%, the glucose measurement 2 hours following an OGTT will very likely be ≥200 mg/dL. But if the hemoglobin A1c is between 5.7% and 6.5%, the person might be diagnosed with T2DM if they had a 2-hr OGTT.6

In one study, 1,241 nondiabetic, overweight, or obese participants had all 3 tests to diagnose T2DM.7 The 2-hr OGTT diagnosed T2DM in 148 participants (12%). However, the hemoglobin A1c test only diagnosed T2DM in 78 of the 148 participants who were diagnosed with T2DM based on the 2-hr OGTT, missing 47% of the cases of T2DM. In this study, using the 2-hr OGTT as the “gold standard” reference test, the hemoglobin A1c test had a sensitivity of 53% and specificity of 97%.7

In clinical practice one approach is to explain to the patient the pros and cons of the 3 tests for T2DM and ask them to select the test they prefer to complete. In a high-risk population, including people with obesity, completing any of the 3 tests is better than not testing for diabetes. It also should be noted that, among people who have a normal body mass index (BMI), a “prediabetes” diagnosis is controversial. Compared with obese persons with prediabetes, people with a normal BMI and prediabetes diagnosed by a blood test progress to diabetes at a much lower rate. The value of diagnosing prediabetes after 70 years of age is also controversial because few people in this situation progress to diabetes.8 Clinicians should be cautious about diagnosing prediabetes in lean or elderly people.

The reliability of the hemoglobin A1c test is reduced in conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover, including sickle cell disease, pregnancy (second and third trimesters), hemodialysis, recent blood transfusions or erythropoietin therapy. In these clinical situations, only blood glucose measurements should be used to diagnose prediabetes and T2DM.6 It should be noted that concordance among any of the 3 tests is not perfect.6

Continue to: A 2-step approach to diagnosing T2DM...