Preeclampsia complicates 3% to 8% of pregnancies.1-3 The incidence of preeclampsia is influenced by the clinical characteristics of the pregnant population, including the prevalence of overweight, obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes, nulliparity, advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, kidney disease, and a history of preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy.4

Magnesium treatment reduces the rate of eclampsia among patients with preeclampsia

For patients with preeclampsia, magnesium treatment reduces the risk of seizure. In the Magpie trial, 9,992 pregnant patients were treated for 24 hours with magnesium or placebo.5 The magnesium treatment regimen was either a 4-g IV bolus over 10 to 15 minutes followed by a continuous infusion of 1 g/hr or an intramuscular regimen (10-g intramuscular loading dose followed by 5 g IM every 4 hours). Eclamptic seizures occurred in 0.8% and 1.9% of patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively (relative risk [RR], 0.42; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.29 to 0.60). Among patients with a multiple gestation, the rate of eclampsia was 2% and 6% in the patients treated with magnesium or placebo, respectively. The number of patients who needed to be treated to prevent one eclamptic event was 63 and 109 for patients with preeclampsia with and without severe features, respectively. Intrapartum treatment with magnesium also reduced the risk of placental abruption from 3.2% for the patients receiving placebo to 2.0% among the patients treated with magnesium (RR, 0.67; 99% CI, 0.45- 0.89). Maternal death was reduced with magnesium treatment compared with placebo (0.2% vs 0.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant.

In the Magpie trial, side effects were reported by 24% and 5% of patients treated with magnesium and placebo, respectively. The most common side effects were flushing, nausea, vomiting, and muscle weakness. Of note, magnesium treatment is contraindicated in patients with myasthenia gravis because it can cause muscle weakness and hypoventilation.6 For patients with preeclampsia and myasthenia gravis, levetiracetam may be utilized to reduce the risk of seizure.6

Duration of postpartum magnesium treatment

There are no studies with a sufficient number of participants to definitively determine the optimal duration of postpartum magnesium therapy. A properly powered study would likely require more than 16,000 to 20,000 participants to identify clinically meaningful differences in the rate of postpartum eclampsia among patients treated with magnesium for 12 or 24 hours.7,8 It is unlikely that such a study will be completed. Hence, the duration of postpartum magnesium must be based on clinical judgment, balancing the risks and benefits of treatment.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends continuing magnesium treatment for 24 hours postpartum. They advise, “For patients requiring cesarean delivery (before the onset of labor), the infusion should ideally begin before surgery and continue during surgery, as well as 24 hours afterwards. For patients who deliver vaginally, the infusion should continue for 24 hours after delivery.”9

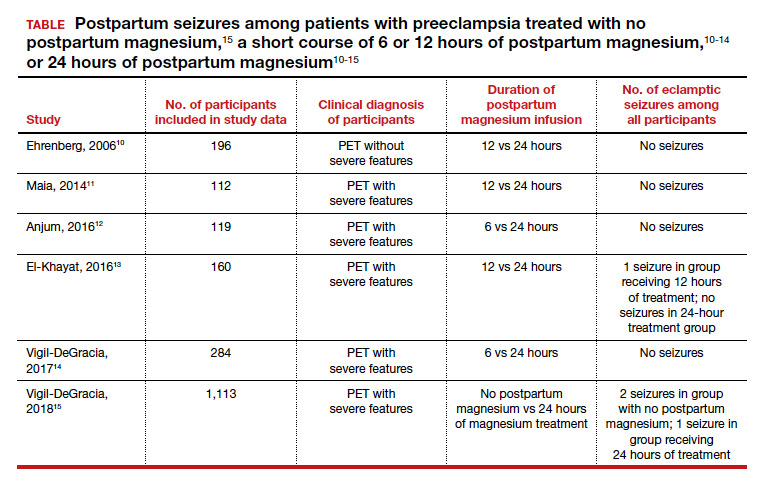

Multiple randomized trials have reported on the outcomes associated with 12 hours versus 24 hours of postpartum magnesium therapy (TABLE). Because the rate of postpartum eclamptic seizure is very low, none of the studies were sufficiently powered to provide a definitive answer to the benefits and harms of the shorter versus longer time frame of magnesium therapy.10-15

Continue to: The harms of prolonged postpartum magnesium infusion...