Cervical cancer is an important global health problem with an estimated 604,127 new cases and 341,831 deaths in 2020.1 Nearly 85% of the disease burden affects individuals from low and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) set forth the goal for all countries to reach and maintain an incidence rate of below 4 per 100,000 women by 2030 as part of the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer.

Although traditional Pap cytology has been the cornerstone of screening programs, its poor sensitivity of approximately 50% and limitations in accessibility require new strategies to achieve the elimination of cervical cancer.2 The discovery that persistent infection with oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) is an essential step in the development of cervical cancer led to the development of diagnostic HPV tests, which have higher sensitivity than cytology (96.1% vs 53.0%) but somewhat lower specificity (90.7% vs 96.3%) for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 or worse lesions.2 Initially, HPV testing was incorporated as a method to triage atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) cytology results.3 Later, the concept of cotesting with cytology emerged,4,5 and since then, several clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of primary HPV screening.6-9

In 2020, the WHO recommended HPV DNA testing as the primary screening method starting at the age of 30 years, with regular testing every 5 to 10 years, for the general population.10 Currently, primary HPV has been adopted in multiple countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, Turkey, England, and Argentina.

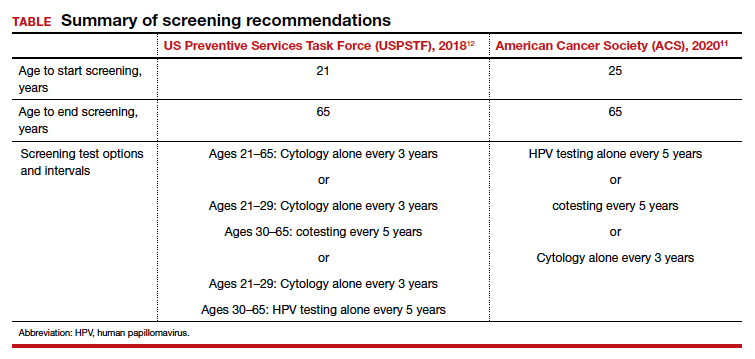

In the United States, there are 3 currently acceptable screening strategies: cytology, cytology plus HPV (cotesting), and primary HPV testing (TABLE). The American Cancer Society (ACS) specifically states that HPV testing alone every 5 years is preferred starting at age 25 years; cotesting every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years are also acceptable.11 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that cytology alone every 3 years starting at 21 years and then HPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years or cytology every 3 years starting at age 30 are all acceptable strategies.12

When applying these guidelines, it is important to note that they are intended for the screening of patients with all prior normal results with no symptoms. These routine screening guidelines do not apply to special populations, such as those with a history of abnormal results or treatment, a history of immunosuppression,13 a history of HPV-related vulvar or vaginal dysplasia,14-16 or a history of hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no prior history of cervical dysplasia.17,18 By contrast, surveillance is interval testing for those who have either an abnormal prior test result or treatment; these may be managed per risk-based estimates provided by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP).18,19 Finally, diagnosis is evaluation (which may include diagnostic cytology) of a patient with abnormal signs and/or symptoms (such as bleeding, pain, discharge, or cervical mass).

In this Update, we present the evidence for primary HPV testing, the management options for a positive result in the United States, and research that will improve uptake of primary HPV testing as well as accessibility.

Change in screening paradigm: Evidence for primary HPV testing

HPV DNA tests are multiplex assays that detect the DNA of targeted high-risk HPV types, using multiple probes, either by direct genomic detection or by amplification of a viral DNA fragment using polymerase chain reaction (PCR).20,21 Alternatively, HPV mRNA-based tests detect the expression of E6 and E7 oncoproteins, a marker of viral integration.20 In examining the data from well-conducted clinical trials, 2 important observations are that different HPV assays were used and that direct comparison may not be valid. In addition, not all tests used in the studies are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing.

Continue to: FDA-approved HPV tests...