Impact of flow disruptions

Flow disruptions (FDs) were found to be more common in RAS. Catchpole and colleagues identified a mean of 9.62 FDs per hour in 89 robotic procedures, including hysterectomies and sacrocolpopexies, from a variety of fields; FDs occurred more often during the docking stage, followed by the console time, and they mostly were caused by communication breakdown and lack of team familiarity.2

Surgeon experience significantly reduced FDs. Surgeons who had done more than 700 RAS cases experienced 60% fewer FDs than those who had done less than 250 cases (13 vs 8 per hour).2 A study focusing on residents’ impact on RAS outcomes found that each FD increased the total operative time by an average 2.4 minutes, with the number significantly higher when a resident was involved.3 About one-quarter of the training-related FDs were procedure-specific instructions, while one-third were related to instrument and robotic instruction. However, pauses to teach residents did not appear to create significant intraoperative delays. Expectedly, experienced surgeons could anticipate and reduce these disruptions by supporting the whole team.

Human ergonomics, turnover time, and robot-specific skills

In a study of human ergonomics in RAS, Yu and colleagues noted that bedside assistants could experience neck posture problems. Surprisingly, the console could constrain the surgeon’s neck-shoulder region.4 Studies that reported on communication problems in a robotic OR suggest that innovative forms of verbal and nonverbal communication may support successful team communication.5

On the learning curve for RAS, OR turnover time, a key value metric, has been longer. However, turnover time was reduced almost by half from 99.2 to 53.2 minutes over 3 months after concepts from motor racing pit stops were employed, including briefings, leadership, role definition, task allocation, and task sequencing. Average room-ready time also was lowered from 42.2 to 27.2 minutes.6 RAS presents new challenges with sterile instrument processing as well. A successful RAS program, therefore, has organizational needs that include the training of OR and sterile processing staff and appropriate shift management.1

In a robotic OR, not only the surgeon but also the whole team requires robot-specific skills. New training approaches to teamwork, communication, and situation awareness skills are necessary. Robotic equipment, with its data and power cables, 2 consoles, and changing movement paths, necessitate larger rooms with a specific layout.7

In a review of recordings of RAS that used a multidimensional assessment tool to measure team effectiveness and cognitive load, Sexton and colleagues identified anticipation, active team engagement, and higher familiarity scores as the best predictors of team efficiency.8 Several studies emphasized the need for a stable team, especially in the learning phase of robotic surgery.5,9,10 A dedicated robotic team reduced the operative time by 18% during robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy (RASCP).10 RASCP procedures that extended into the afternoon took significantly longer time.9 A dedicated anesthesiologist improved the preoperative time.9 Surgical team handoffs also have reduced OR efficiency.11,12

Studying the impact of human factors is paramount for safe and efficient surgery. It is especially necessary in ORs that are equipped with high technologic instruments such as those used in RAS.

Surgical Black Box: Using data for OR safety and efficiency

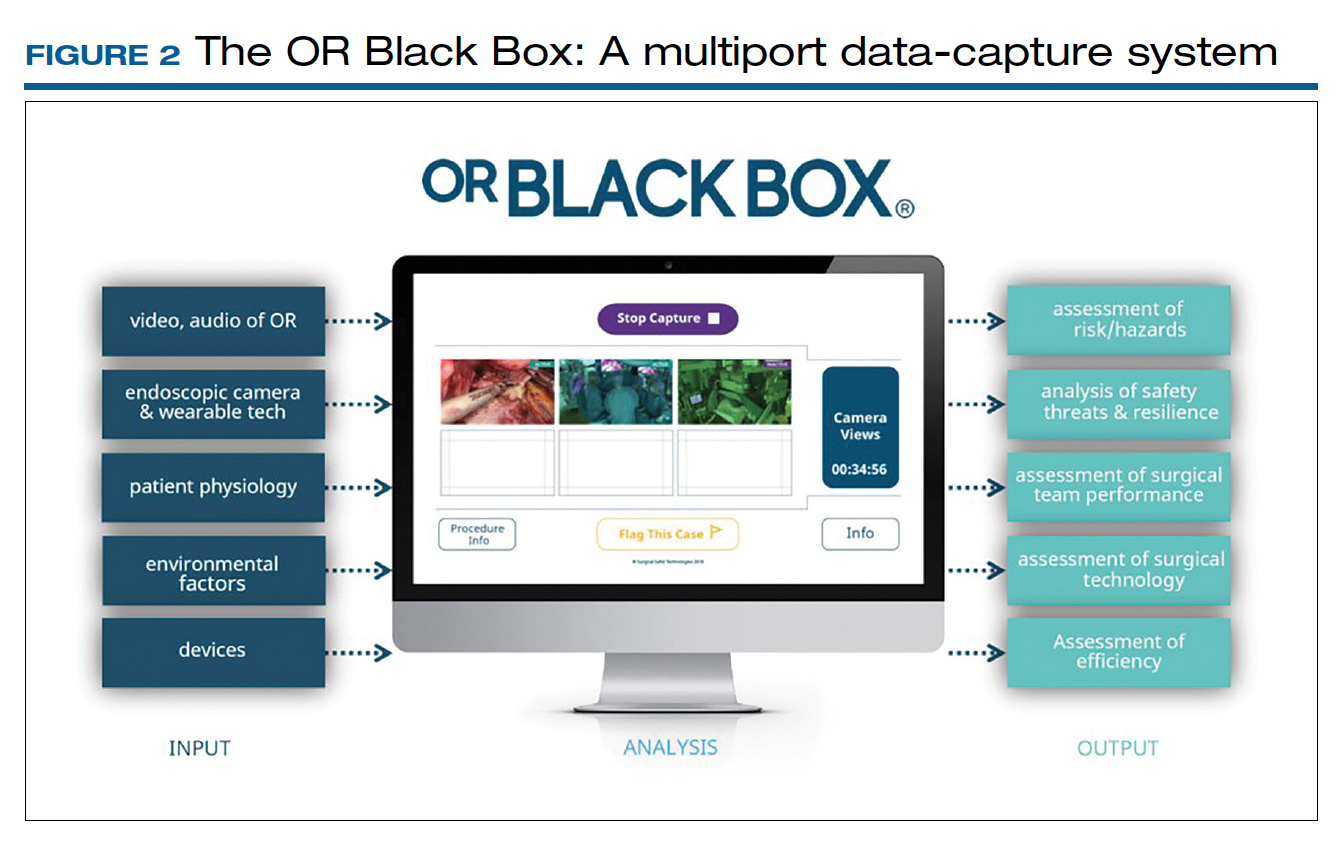

Surgical procedures account for more than 50% of medical errors in a hospital setting, many of which are preventable. Postevent analysis with traditional methods, such as “Morbidity and Mortality” meetings held many days later, misses many adverse events in the OR.13 Another challenge with ever-changing and fast-multiplying surgical approaches is the development of effective surgical skill. Reviewing video recording of surgical procedures has been proposed as an instrument for recognizing adverse events and perfecting surgical skills.Recently, an innovative data-capture platform called the OR Black Box, developed by Teodor Grantcharov, MD, PhD, and colleagues, went beyond simple audiovisual recording.14 This high technologic platform not only video records the actual surgical procedure with laparoscopic camera capture (and wearable cameras for open cases) but also monitors the entire OR environment via wide-angle cameras, utilizes sensors, and records both the patient’s and the surgeon’s physiologic parameters.

The OR Black Box generates a holistic view of the OR after synchronization, encryption, and secure storage of all inputs for further analysis by experts and software-based algorithms (FIGURE 2). Computer vision algorithms can recognize improper dissection techniques and complications, such as bleeding. Adverse events are flagged with an automated software on a procedural timeline to facilitate review of procedural steps, disruptive environmental and organizational factors, OR team technical and nontechnical skills, surgeon physiologic stress, and intraoperative errors, events, and rectification processes using validated instruments.

Artificial intelligence built into this platform can automatically extract objective, high-quality, and structured data to generate explainable insights by recognizing adverse events and procedural segments of interest for training and quality improvement and provide a foundation with objective measurements of technical and nontechnical performance for formative and summative assessment. This system, a major step up compared with retrospective review of likely biased medical records and labor-intensive multidisciplinary human observers, has the potential to increase efficiency and reduce costs by studying human factors that include clinical design, technology, and organization. OR efficiency, measured in real time objectively and thoroughly, may save time and resources.

OR Black Box platforms have already started to generate meaningful data. It is not surprising that auditory disruptions—OR doors opening, loud noises, pagers beeping, telephones ringing—were recorded almost every minute during laparoscopic procedures.15 Most technical errors occurred during dissection, resection, and reconstruction and most commonly were associated with improper estimations of force applied to tissue and distance to the target tissue during operative steps of a laparoscopic procedure.16 Another study based on this system showed that technical performance was an independent predictor of postoperative outcomes.17 The OR Black Box identified a device-related interruption in 30% of elective laparoscopic general surgery cases, most commonly in sleeve gastrectomy and oncologic gastrectomy procedures. This sophisticated surgical data recording system also demonstrated a significantly better ability to detect Veress needle injuries (12 vs 3) and near misses (47 vs 0) when compared with traditional chart review.18

Data from the OR Black Box also have been applied to better analyze nontechnical performance, including teamwork and interpersonal dynamics.19 Surgeons most commonly exhibited adept situational awareness and leadership, while the nurse team excelled at task management and situational awareness.19 Of the total care provider team studied, the surgeon and scrub nurse demonstrated the most favorable nontechnical behavior.19 Of note, continuous physiologic monitoring of the surgeon with this system revealed that surgeons under stress had 66% higher adverse events.

The OR Black Box is currently utilized at 20 institutions in North America and Europe. The data compiled from all these institutions revealed that there was a 10% decrease in intraoperative adverse events for each 10-point increase in technical skill score on a scale of 0 to 100 (unpublished data). This centralized data indicated that turnover time ranged widely between 7 and 91 minutes, with variation of cleanup time from 1 to 25 minutes and setup time from 22 to 43 minutes. Institutions can learn from each other using this platform. For example, the information about block time utilization (20%–99%) across institutions provides opportunities for system improvements.

With any revolutionary technology, it is imperative to study its effects on outcomes, training, costs, and privacy before it is widely implemented. We, obstetricians and gynecologists, are very familiar with the impact of electronic fetal monitoring, a great example of a technologic advance that did not improve perinatal outcomes but led to unintended consequences, such as higher rates of cesarean deliveries and lawsuits. Such a tool may lead to potential misrepresentation of intraoperative events unless legal aspects are clearly delineated. As exciting as it is, this disruptive technology requires further exploration with scientific vigor.

Continue to: Surgeon and hospital volume: Surgical outcomes paradigm...