CASE Placenta accreta spectrum following uncomplicated vaginal delivery

Imagine you are an obstetric hospitalist taking call at a level II maternal level of care hospital. Your patient is a 35-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, with a past history of retained placenta requiring dilation and curettage and intravenous antibiotics for endomyometritis. This is an in vitro fertilization pregnancy that has progressed normally, and the patient labored spontaneously at 38 weeks’ gestation. Following an uncomplicated vaginal delivery, the placenta has not delivered, and you attempt a manual placental extraction after a 40-minute third stage. While there is epidural analgesia and you can reach the uterine fundus, you are unable to create a separation plane between the placenta and uterus.

What do you do next?

Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) includes a broad range of clinical scenarios with abnormal placental attachment as their common denominator. The condition has classically been defined pathologically, with chorionic villi attaching directly to the myometrium (“accreta”) or extending more deeply into the myometrium (“increta”) or attaching to surrounding tissues and structures (“percreta”).1 It is most commonly encountered in patients with low placental implantation on a prior cesarean section scar; indeed, placenta previa, particularly with a history of cesarean delivery, is the strongest risk factor for the development of PAS.2 In addition to abnormal placental attachment, these placental attachments are often hypervascular and can lead to catastrophic hemorrhage if not managed appropriately. For this reason, patients with sonographic or radiologic signs of PAS should be referred to specialized centers for further workup, counseling, and delivery planning.3

Although delivery at a specialized PAS center has been associated with improved patient outcomes,4 not all patients with PAS will be identified in the antepartum period. Ultrasonography may miss up to 40% to 50% of PAS cases, particularly when the sonologist has not been advised to look for the condition,5 and not all patients with PAS will have a previa implanted in a prior cesarean scar. A recent study found that these patients with nonprevia PAS were identified by imaging less than 40% of the time and were significantly less likely to be managed by a specialized team of clinicians.6 Thus, it falls upon every obstetric care provider to be aware of this diagnosis, promptly recognize its unanticipated presentations, and have a plan to optimize patient safety.

Step 1: Recognition

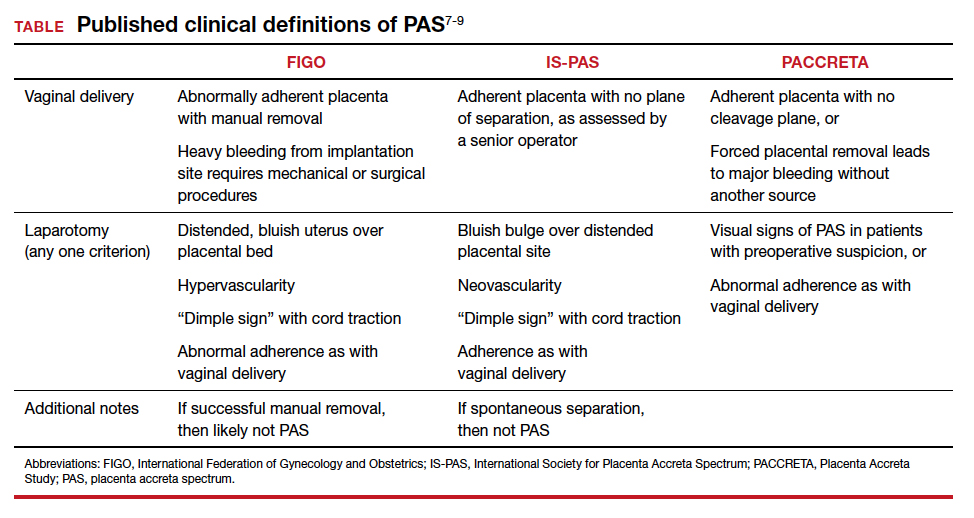

While PAS is classically defined as a pathologic condition, no clinician has the luxury of histology in the delivery room. Researchers have variously defined PAS clinically, with the common trait of abnormal placental adherence.7-9 The TABLE compares published definitions that have been used in the literature. While some definitions include hemorrhage, no clinician wants to induce significant hemorrhage to confirm their patient’s diagnosis. Thus, practically, the clinical PAS diagnosis comes down to abnormal placental attachment: If it is apparent that some or all of the placenta will not separate from the uterine wall with digital manipulation or careful curettage, then PAS should be suspected, and appropriate steps should be taken before further removal attempts.

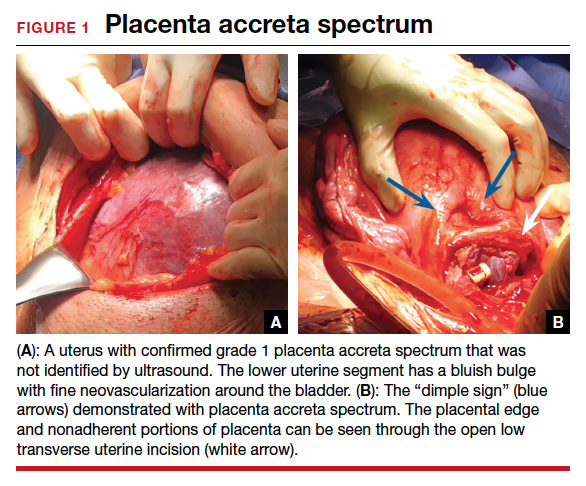

At cesarean delivery, the PAS diagnosis may be aided by visual cues. With placenta previa, the lower uterine segment may bulge and take on a bluish hue, distinctly different from the upper healthy myometrium. PAS may also manifest with neovascularization, particularly behind the bladder. As with vaginal births, the placenta will fail to separate after the delivery, and controlled traction on the umbilical cord can produce a “dimple sign,” or visible myometrial retraction at the site of implantation (FIGURE 1). Finally, if the diagnosis is still in doubt, attempts to gently form a cleavage plane between the placenta and myometrium will be unsuccessful if PAS is present.8

Step 2: Initial management—pause, plan

Most importantly, do not attempt to forcibly remove the placenta. It can be left attached to the uterus until appropriate resources are secured. Efforts to forcibly remove an adherent placenta may well lead to major hemorrhage, and thus it falls on the patient’s care team to pause and plan for PAS care at this point. FIGURE 2 displays an algorithm for patient management. Further steps depend primarily on whether or not the patient is already hemorrhaging. In a stable situation, the patient should be counseled regarding the abnormal findings and the suspected PAS diagnosis. This includes the possibility of further procedures, blood transfusion, and hysterectomy. Local resources, including nursing, anesthesia, and the blood bank, should be notified about the situation and for the potential to call in specialized services. If on-site experienced specialists are not available, then patient transfer to a PAS specialty center should be strongly considered. While awaiting additional help or transport, the patient requires close monitoring for gross and physiologic signs of hemorrhage. If pursued, transport to a PAS specialty center should be expedited.

If the patient is already hemorrhaging or unstable, then appropriate local resources must be activated. At a minimum, this requires an obstetrician and anesthesiologist at the bedside and activation of hemorrhage protocols (eg, a massive transfusion protocol). If blood products are unavailable, consider whether they can be transported from other nearby blood banks, and start that process promptly. Next, contact backup services. Based on local resources and clinical severity, this may include maternal-fetal medicine specialists, pelvic surgeons, general and trauma surgeons, intensivists, interventional radiologists, and transfusion specialists. Even if the patient cannot be safely transferred to another hospital, the obstetrician can call an outside PAS specialist to discuss next steps in care and begin transfer plans, assuming the patient can be stabilized. Based on the Maternal Levels of Care definitions published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine,10 patients with PAS should be managed at level III or level IV centers. However, delivery units at every level of maternal care should have a protocol for securing local help and reaching an appropriate consultant if a PAS case is encountered. Know which center in your area specializes in PAS so that when an unanticipated case arises, you know who to call.

Continue to: Step 3: Ultimate management—mobilize and prepare for bleeding...