Surgical repair

VVF repair. Factors that influence successful repair of VVF include the size and number of fistula, location, degree of scarring, bladder capacity, and urethral length.

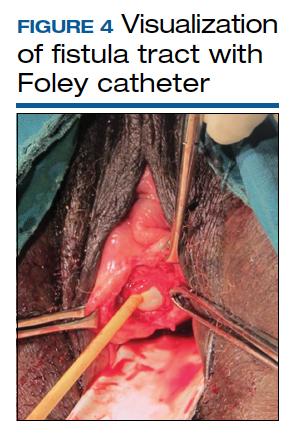

Surgical technique requires wide mobilization and adequate exposure. The fistula tract can be delineated and manipulated with a pediatric Foley catheter, ureteral stent, or even a ureteral guidewire to aid in dissection (FIGURE 4). Intraoperative visualization of the ureters, including stenting, often is needed. The fistulous track is excised depending on the level of scarring. Closure of the bladder uroepithelium for the first layer is with absorbable interrupted 3-0 or 2-0 sutures in a tension-free closure. The bladder is then evaluated with a retrograde fill with saline and methylene blue to ensure a watertight closure for the first layer. If the first layer is not watertight, the second layer closure will not compensate and the fistula will persist. Particular attention is paid to the angles of the fistula at the first layer closure to prevent recurrence of the fistula at the angles. A running second layer with absorbable 2-0 suture is done. At times, a Martius flap or an omental J flap can be used to provide an additional layer for support and to increase vascularity.10 The patient is sent home with a Foley catheter for drainage for 10 to 14 days.11 Antibiotics are not needed postoperatively for VVF surgery.12

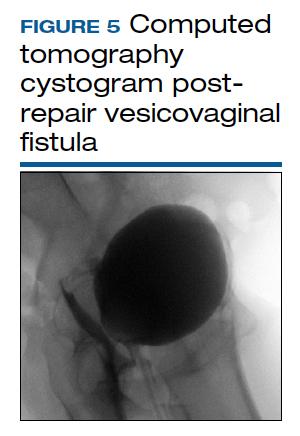

CT cystogram or retrograde cystogram is usually done to evaluate closure of the fistula prior to removal of the Foley catheter; retrograde fill with contrast directly into the bladder with 300 mL is sufficient (FIGURE 5). Patients are advised to refrain from sexual activity for a minimum of 6 weeks, but depending on the level of complexity and scarring, this can be up to 12 weeks.

The success rate in general is in the 95% range. Patients with successful closure of VVF are at risk for urge incontinence due to decreased bladder capacity, stress incontinence especially if the continence mechanism or urethra is involved, vaginal scarring, dyspareunia, and infertility.13 In general, sexual function improves after surgical repair.

RVF repair. Prior to surgical repair of RVF, the integrity of the external anal sphincter must be determined. If it is not involved, a vertical incision is made in the posterior vaginal wall, the vaginal epithelium is separated from the vaginal muscularis, and the fistula tract is identified. After complete wide mobilization of the tissue surrounding the tract, it is excised. The rectal wall is repaired with 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable interrupted sutures; a second layer and if possible even a third layer and finally the vaginal epithelium are all closed with 2-0 absorbable interrupted sutures.

If the sphincter complex is involved, the dissection involves an inverted U incision separating the vaginal wall from the rectum. The fistula tract is excised, the rectal wall is closed, and the internal anal sphincter is identified and reapproximated with interrupted absorbable 2-0 or 0 sutures. The disrupted external sphincter is then reapproximated with 2-0 or 0 sutures, and finally the transverse perineal and bulbocavernosus muscles are brought together with Lembert 0 sutures prior to closure of the external skin. Perioperative antibiotics have been shown to improve success rates in the correction of RVF.5 In patients with sphincter trauma and known RVF, outcomes with a sphincteroplasty are better, compared with endorectal advancement flaps. The patient is discharged with a bowel regimen and dietary precautions that aim for daily soft bowel movements.

After surgical treatment of fistulas, patients benefit from pelvic floor physical therapy that focuses on pelvic floor strengthening. Incorporating the habit of Kegel exercises after every void, timed (scheduled) bladder voiding, and avoidance of straining with urination or defecation should be emphasized.

Continue to: CASE 1 Pregnant woman with rectal bleeding...