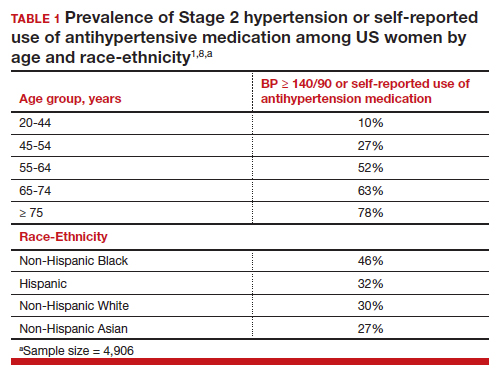

Hypertension is a prevalent medical problem among US women, with a higher prevalence among Black women, than among White, Hispanic, or Asian women (TABLE 1).1 Among US women aged 55 to 64 years, approximately 50% have hypertension or are taking a hypertension medicine.1 Hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including stroke, coronary heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and peripheral vascular disease.1,2 In a study of 1.3 million people, blood pressure (BP) ≥ 130/80 mm Hg was associated with an increased risk of a cardiovascular event, including myocardial infarction and stroke.2 Excessive sodium intake is an important risk factor for developing hypertension.3 In 2015–2016, 87% of US adults consumed >2,300 mg/d of sodium,4 an amount that is considered excessive.1 Less well known is the association between low potassium intake and hypertension. This editorial reviews the evidence that diets high in sodium and low in potassium contribute to the development of hypertension and cardiovascular disease.

Sodium and potassium dueling cations

Many cohort studies report that diets high in sodium and low in potassium are associated with hypertension and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. For example, in a cohort of 146,000 Chinese people, high sodium and low potassium intake was positively correlated with higher BP.5 In addition, the impact of increasing sodium intake or decreasing potassium intake was greater for people with a BMI ≥24 kg/m2, than people with a BMI <24 kg/m2. In a cohort of 11,095 US adults, high sodium and low potassium intake was associated with an increased risk of hypertension.6

In a study of 13,696 women, high potassium intake was associated with lower BP in participants with either a low or high sodium intake.7 In addition, over a 19-year follow up, higher potassium intake was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events.7 Comparing the highest (5,773 mg/d) vs lowest (2,783 mg/d) tertile of potassium intake, the decreased risk of a cardiovascular event was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.83–0.95).7

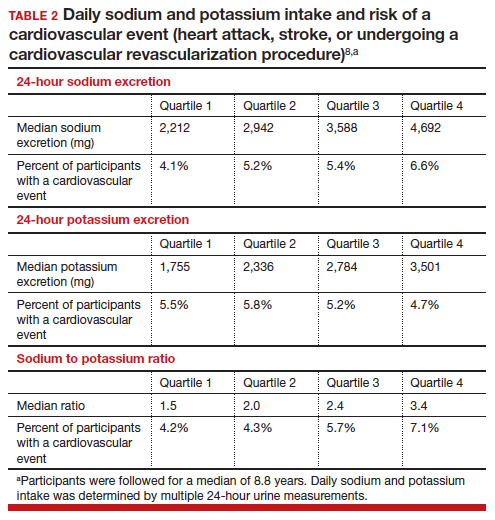

In a meta-analysis of data culled from 6 cohort studies, 10,709 adults with a mean age of 52 years, 54% of whom identified as women, were followed for a median of 8.8 years.8 Each adult contributed at least two 24-hour urine samples for measurement of sodium and potassium content. (Measurement of sodium and potassium in multiple 24-hour urine specimens from the same participant is thought to be the best way to assess sodium and potassium consumption.) The primary outcome was a cardiovascular event, including heart attack, stroke, or undergoing coronary revascularization procedures. In this study increasing consumption of sodium was associated with an increase in cardiovascular events, and increasing consumption of potassium was associated with a decrease in cardiovascular events. The hazard ratio for a cardiovascular event comparing high versus low consumption of sodium was 1.60 (95% CI, 1.19–2.14), and comparing high versus low consumption of potassium was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.51–0.91) (TABLE 2).8

Continue to: Clinical trial data on decreasing Na and/or increasing K consumption on CV outcomes...