Current use of endometrial ablation in the US

In 2015, more than 500,000 endometrial ablations were performed in the United States.Given the ability to perform in-office ablation, this number is growing and potentially underestimated each year.6 In 2022, the global endometrial ablation market was valued at $3.4 billion, a figure projected to double in 10 years.7 The procedure has evolved as different devices and approaches have developed, offering patients different means to manage bleeding without hysterectomy. The minimally invasive procedure, performed in premenopausal patients with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) due to benign causes who have completed childbearing, has been associated with faster recovery times and fewer short-term complications compared with more invasive surgery.8 There are several non-resectoscope ablative devices approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and each work to destroy the endometrial lining via thermal or cryoablation. Endometrial ablation can be performed in premenopausal patients with HMB due to benign causes who have completed childbearing.

Recently, promotional literature has begun to report on so-called overuse of hysterectomy, despite decreasing overall hysterectomy rates. This reporting proposes and applies “appropriateness criteria,” accounting for the rate of preoperative counseling regarding alternatives to hysterectomy, as well as the rate of “unsupportive” final pathology.9 The adoption of endometrial ablation and increasing market value of such vendors suggest that this campaign is having its desired effect. From the oncology perspective, we are concerned the pendulum could swing too far away from hysterectomy, a procedure that definitively cures abnormal uterine bleeding, toward endometrial ablation without explicit acknowledgement of the trade-offs involved.

Endometrial ablation complications: Late-onset procedure failure

A number of post-ablation syndromes may present at least 1 month following the procedure. Collectively known as late-onset endometrial ablation failure (LOEAF), these syndromes are characterized by recurrent vaginal bleeding, and/or new cyclic pelvic pain.10 It is difficult to measure the true incidence of LOEAF. Thomassee and colleagues examined a Canadian retrospective cohort of 437 patients who underwent endometrial ablation; 20.8% reported post-ablation pelvic pain after a median 301 days.11 The subsequent need for surgical intervention, often hysterectomy, is a surrogate for LOEAF.

It should be noted that LOEAF is distinct from post-ablation tubal sterilization syndrome (PATSS), which describes cornual menstrual bleeding impeded by the ligated proximal fallopian tube.12 Increased awareness of PATSS, along with the discontinuation of Essure (a permanent hysteroscopic sterilization device) in 2018, has led some surgeons to advocate for concomitant salpingectomy at the time of endometrial ablation.13 The role of opportunistic salpingectomy in primary prevention of epithelial ovarian cancer is well described, and while we strongly support this practice at the time of endometrial ablation, we do not feel that it effectively prevents LOEAF.14

The post-ablation inability to adequately sample the endometrium is also considered a LOEAF. A prospective study of 57 women who underwent endometrial ablation assessed post-ablation sampling feasibility via transvaginal ultrasonography, saline infusion sonohysterography (SIS), and in-office endometrial biopsies. In 23% of the cohort, endometrial sampling failed, and the authors noted decreased reliability of pathologic assessment.15 One systematic review, in which authors examined the incidence of endometrial cancer following endometrial ablation, characterized 38 cases of endometrial cancer and reported a post-ablation endometrial sampling success rate of 89%. This figure was based on a self-selected sample of 18 patients; cases in which endometrial sampling was thought to be impossible were excluded. The study also had a 30% missing data rate and several other biases.16

In the previously mentioned poll of SGO members,1 84% of the surveyed gynecologic oncologists managing post-ablation patients reported that endometrial sampling following endometrial ablation was “moderately” or “extremely” difficult. More than half of the survey respondents believed that hysterectomy was required for accurate diagnosis.1 While we acknowledge the likely sampling bias affecting the survey results, we are not comforted by any data that minimizes this diagnostic challenge.

Appropriate patient selection and contraindications

The ideal candidate for endometrial ablation is a premenopausal patient with HMB who does not desire future fertility. According to the FDA, absolute contraindications include pregnancy or desired fertility, prior ablation, current IUD in place, inadequate preoperative endometrial assessment, known or suspected malignancy, active infection, or unfavorable anatomy.17

What about patients who may be at increased risk for endometrial cancer?

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of endometrial ablation in patients at increased risk for developing endometrial cancer in the future. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2007 practice bulletin on endometrial ablation (no longer accessible online) alludes to this concern and other contraindications,18 but there are no established guidelines. Currently, no ACOG practice bulletin or committee opinion lists relative contraindications to endometrial ablation, long-term complications (except risks associated with future pregnancy), or risk of subsequent hysterectomy. The risk that “it may be harder to detect endometrial cancer after ablation” is noted on ACOG’s web page dedicated to frequently asked questions (FAQs) regarding abnormal uterine bleeding.19 It is not mentioned on their web page dedicated to the FAQs regarding endometrial ablation.20

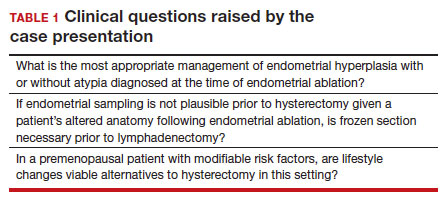

In the absence of high-quality published data on established contraindications for endometrial ablation, we advocate for the increased awareness of possible relative contraindications—namely well-established risk factors for endometrial cancer (TABLE 1).For example, in a pooled analysis of 24 epidemiologic studies, authors found that the odds of developing endometrial cancer was 7 times higher among patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2, compared with controls (odds ratio [OR], 7.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.33–8.06).21 Additionally, patients with Lynch syndrome, a history of extended tamoxifen use, or those with a history of chronic anovulation or polycystic ovary syndrome are at increased risk for endometrial cancer.22-24 If the presence of one or more of these factors does not dissuade general gynecologists from performing an endometrial ablation (even armed with a negative preoperative endometrial biopsy), we feel they should at least prompt thoughtful guideline-driven pause.

Continue to: Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option...