Hysterectomy—A disincentivized option

The annual number of hysterectomies performed by general gynecologists has declined over time. One study by Cadish and colleagues revealed that recent residency graduates performed only 3 to 4 annually.25 These numbers partly reflect the decreasing number of hysterectomies performed during residency training. Furthermore, other factors—including the increasing rate of placenta accreta spectrum, the focus on risk stratification of adnexal masses via the ovarian-adnexal reporting and data classification system (O-RADs), and the emphasis on minimally invasive approaches often acquired in subspecialty training—have likely contributed to referral patterns to such specialists as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and gynecologic oncologists.26 This trend is self-actualizing, as quality metrics funnel patients to high-volume surgeons, and general gynecologists risk losing hysterectomy privileges.

These factors lend themselves to a growing emphasis on endometrial ablation. Endometrial ablations can be performed in several settings, including in the hospital, in outpatient clinics, and more and more commonly, in ambulatory surgery centers. This increased access to endometrial ablation in the ambulatory surgery setting has corresponded with an annual endometrial ablation market value growth rate of 5% to 7%.27 These rates are likely compounded by payer reimbursement policies that promote endometrial ablation and other alternatives to hysterectomy that are cost savings in the short term.28 While the actual payer models are unavailable to review, they may not consider the costs of LOEAFs, including subsequent hysterectomy up to 5 years after initial ablation procedures. Provocatively, they almost certainly do not consider the costs of delayed care of patients with endometrial cancer vying for gynecologic oncology appointment slots occupied by post-ablation patients.

We urge providers, patients, and advocates to question who benefits from the uptake of ablation procedures: Patients? Payors? Providers? And how will the field of gynecology fare if hysterectomy skills and privileges are supplanted by ablation?

Post-ablation bleeding: Management by the gyn oncologist

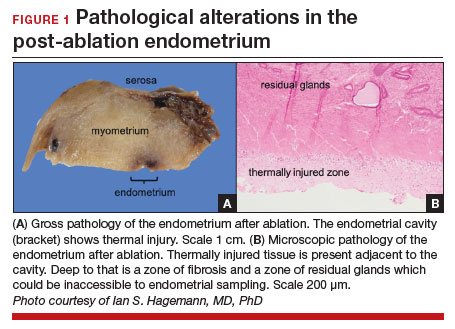

Patients with post-ablation bleeding, either immediately or years later, are sometimes referred to a gynecologic oncologist given the possible risk for cancer and need for surgical staging if cancer is found on the hysterectomy specimen. In practice, assuming normal preoperative ultrasonography and no other clinical or radiologic findings suggestive of malignancy (eg, computed tomography findings concerning for metastases, abnormal cervical cytology, etc.), the presence of cancer is extremely unlikely to be determined at the time of surgery. Frozen section is not generally performed on the endometrium; intraoperative evaluation of even the unablated endometrium is notoriously unreliable; and histologic assessment of the ablated endometrium is limited by artifact (FIGURE 1). The abnormalities caused by ablation further impede selection of a representative focus, obfuscating any actionable result.

Some surgeons routinely bivalve the excised uterus prior to fixation to assess presence of tumor, tumor size, and the degree of myometrial invasion.29 A combination of factors may compel surgeons to perform lymphadenectomy if not already performed, or if sentinel lymph node mapping was unsuccessful. But this practice has not been studied in patients with post-ablation bleeding, and applying these principles relies on a preoperative diagnosis establishing the presence and grade of a cancer. Furthermore, the utility of frozen section and myometrial assessment to decide whether or not to proceed with lymphadenectomy is less relevant in the era of molecular classification guiding adjuvant therapy. In summary, assuming no pathologic or radiologic findings suggestive of cancer, gynecologic oncologists are unlikely to perform lymphadenectomy at the time of hysterectomy in these post-ablation cases, which therefore can safely be performed by general gynecologists.

Our recommendations

Consider the LNG-IUD as an alternative to ablation. A recent randomized controlled trial by Beelen and colleagues compared the effectiveness of LNG-releasing IUDs with endometrial ablation in patients with HMB. While the LNG-IUD was inferior to endometrial ablation, quality-of-life measures were similar up to 2 years.31 Realizing that the hysterectomy rate following endometrial ablation increases significantly beyond that time point (2 years), this narrative may be incomplete. A 5- to 10-year follow-up time-frame may be a more helpful gauge of long-term outcomes. This prolonged time-frame also may allow study of the LNG-IUD’s protective effects on the endometrium in the prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

Consider hysterectomy. A 2021 Cochrane review revealed that, compared with endometrial ablation, minimally invasive hysterectomy is associated with higher quality-of-life metrics, higher self-reported patient satisfaction, and similar rates of adverse events.32 While patient autonomy is paramount, the developing step-wise approach from endometrial ablation to hysterectomy, and its potential effects on the health care system at a time when endometrial cancer incidence and mortality rates are rising, is troubling.

Postablation, consider hysterectomy by the general gynecologist. Current trends appear to disincentivize general gynecologists from performing hysterectomy either for HMB or LOEAF. We would offer reassurance that they can safely perform this procedure. Referral to oncology may not be necessary since, in the absence of an established diagnosis of cancer, a lymphadenectomy is not typically required. A shift away from referral for these patients can preserve access to oncology for those women, especially minority women, with an explicit need for oncologic care.

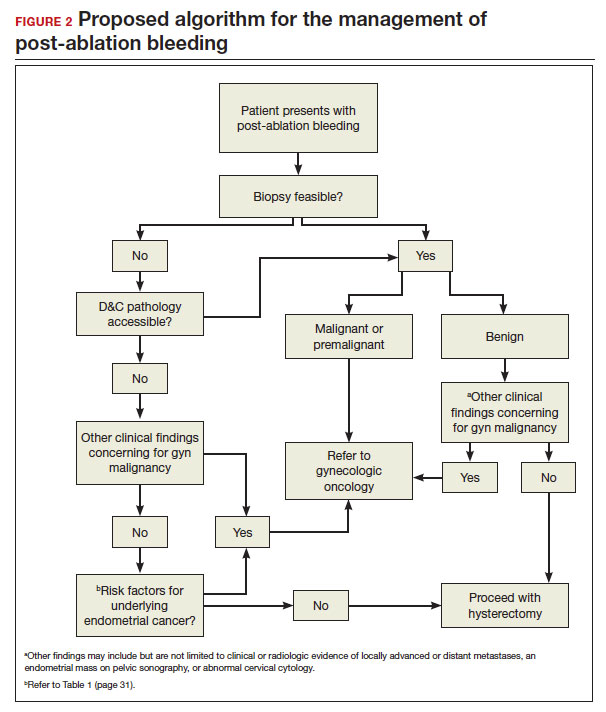

In FIGURE 2, we propose a management algorithm for the patient who presents with post–ablation bleeding. We acknowledge that the evidence base for our management recommendations is limited. Still, we hope providers, ACOG, and other guidelines-issuing organizations consider them as they adapt their own practices and recommendations. We believe this is one of many steps needed to improve outcomes for patients with gynecologic cancer, particularly those in marginalized communities disproportionately impacted by current trends.

CASE Resolution

After reviewing the relevant documentation and examining the patient, the gynecologic oncology consultant contacts the referring gynecologist. They review the low utility of frozen section and the overall low risk of cancer on the final hysterectomy specimen if the patient were to undergo hysterectomy. The consultant clarifies that there is no other concern for surgical complexity beyond the skill of the referring provider, and they discuss the possibility of referral to a minimally invasive specialist for the surgery.

Ultimately, the patient undergoes uncomplicated laparoscopic hysterectomy performed by the original referring gynecologist. Final pathology reveals inactive endometrium with ablative changes and cornual focus of endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. ●

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Ian Hagemann, MD, PhD, for his review of the manuscript.