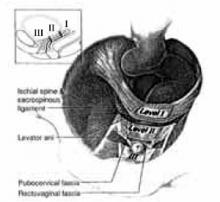

The connective-tissue attachment of the urethra to the pubic bone and laterally to the levator muscle supports the distal vagina (DeLancey Level III). The midvagina is supported by the connective-tissue sheath that surrounds it and its lateral connective-tissue attachments to the levator muscle (DeLancey Level II). The vaginal apex and cervix (DeLancey Level I) are held by the surrounding endopelvic connective tissue—mainly the thickened lateral and posterior portions referred to as the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments (FIGURE 3).9

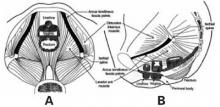

FIGURE 1 The pelvic musculature

These are transabdominal (A) and lateral (B) views of the pelvic floor demonstrating the pelvic musculature.

Reprinted with permission from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Precis: Gynecology, Second Edition. Washington, DC, ©ACOG, 2001.

FIGURE 2 Pelvic connective-tissue network

The heavy black lines in these lateral (A) and coronal (B) views represent the pelvic connective-tissue network known as endopelvic fascia. It demonstrates the continuity of the pelvic connective tissue as it surrounds the pelvic organs and ultimately attaches to the pelvic sidewall.

Reprinted with permission from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Precis: Gynecology, Second Edition. Washington, DC, ©ACOG, 2001.

FIGURE 3 Anatomic and physiologic support mechanisms

This demonstrates the levels of support described by DeLancey. Level I shows connective-tissue fibers extending both cephalad and dorsally toward the sacrum. Level II shows the lateral attachment to the arcus tendineus fascia of the pelvis. Level III shows the lateral attachment and anterior attachment of connective tissue to the lateral arcus tendineus fascia and posterior pubic symphysis.

Reprinted with permission from DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1717-1728.

Physiologic support mechanisms

In addition to the anatomic components of female pelvic-organ support, there are physiologic mechanisms that help maintain the positioning and functioning of pelvic organs. The muscles, vessels, and nerves of the pelvic floor function interactively as a compression mechanism in a manner similar to a valve, maintaining positioning of the viscera. The resting tone of the pelvic floor provides a valvelike closure surrounding the urethra, vagina, and rectum. This mechanism helps to close the genital hiatus, thereby preventing descent of the uterus, vagina, and adjacent structures.10

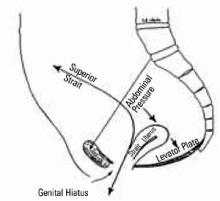

The pelvic axis. The connective-tissue supports of the vagina anchor it to the pelvic skeleton and hold the vagina in the previously described semihorizontal axis. When this axis is maintained, increased abdominal pressure pushes the vaginal tube into the hollow of the sacrum, maintaining an intra-abdominal position (FIGURE 4).5,10

When the connective-tissue supports of the vagina and uterus are broken, the pelvic organs align in a more vertical axis. Increased intra-abdominal pressure causes the pelvic organs to descend through the natural openings in the pelvic floor (genital hiatus). The resulting descent of the uterus and vagina is what we refer to as pelvic organ prolapse. The genital hiatus also may be widened secondary to the trauma of childbirth.5,9,10

FIGURE 4 Connective-tissue supports

This figure demonstrates how the uterus is held over the levator plate. In this position, increases in intra-abdominal pressure push the uterus caudally into the levator plate rather than through the genital hiatus.

Reprinted with permission from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (Obstetrics and Gynecology, 1960, Volume 15, pages 711-726)

Causes of pelvic-support defects

Childbirth. Damage to the levator muscle during childbirth has been associated with the beginning of pelvicorgan dysfunction, either as noticeable descent of the pelvic viscera, or bladder or bowel incontinence. Studies have shown damage to the muscle bundles of the levator and to nerves of the pelvic floor after childbirth, including atrophic and degenerative muscle changes and slowed nerve-conduction velocities.10,11 While there is some evidence of muscle and nerve recovery, these postnatal findings of injury have been generalized to populations at increased risk for pelvic-organ prolapse and fecal and urinary incontinence,12,13 especially multigravid patients and patients with disruption of the anal sphincter.

Age. Aging also has been shown to decrease the functioning of the pelvic-floor muscles. The microscopic findings here are similar to those after childbirth, demonstrating both a loss of muscle substance and degeneration of the nerve supply. In addition, there appears to be atrophy of the remaining musculature.14

Collagen in the pelvis. In addition to an age-related loss of the endopelvic fascia, there also may be inherited differences in the ratio of collagen types and in the quality of the collagen ground substance. This is best exemplified by nulliparous patients who demonstrate pelvic-organ prolapse or joint hypermobility and by patients with hereditary hyperelastosis syndromes.15,16

Estrogen and pelvic-floor dysfunction. The theory that estrogen helps maintain the quality of connective tissue stems from the observation that urinary incontinence and pelvicorgan prolapse seem to begin around the time of menopause. While estrogen may indeed play a role, no prospective study has shown that estrogen replacement has a significant effect on urinary or fecal incontinence.17-19 Nor have any parallels been found in young women who have experienced surgical castration, chemotherapy, or premature ovarian failure.