Prophylaxis may be effective in some patients, but can be challenging. It entails meticulous skin cleansing and careful consideration of where the incision is placed, type of closure, use of a drain, and antibiotic administration.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is based on the theory that its presence in host tissues will alter natural defense mechanisms and kill bacteria that inoculate the wound. Because the window of efficacy is narrow, antibiotics should be administered shortly before the time of inoculation (ie, shortly before the time of incision, vaginal entry, etc.). Current guidelines suggest the use of broad-spectrum agents, including a cephalosporin, approximately 60 minutes before the incision. Redosing is recommended for procedures that last longer than 3 hours, as well as for those that involve significant blood loss (>1,500 mL).

For surgical procedures other than hysterectomy and laparotomy, prophylaxis may not be warranted.3 However, when the patient is markedly obese, many surgeons, including me (Dr. Perkins), sometimes opt to give antibiotics anyway—except for laparoscopic procedures—primarily for wound healing.

Compromised operative exposure

One of the main challenges of surgery in the obese is achieving adequate exposure; when it is inadequate, inadvertent injury may occur.

In addition to a thick abdominal wall composed largely of adipose tissue, these patients frequently have significant accumulations of fat in the mesenteries of the bowel, omentum, and pelvic peritoneum. These accumulations make it difficult to navigate around what becomes a narrow operative field.

Exposure can also be limited in vaginal surgery, because many obese women have very large thighs, buttocks, and accumulations of perineal fat.

Because exposure is a key element of successful surgery, modification of the procedure often becomes necessary—eg, focusing on a single area of the operative field at a time.

Use of a special retractor may help. A self-retaining retractor can be extremely useful. The Bookwalter retractor, first described in 1980, is a commonly used, table-fixed system that attaches to the side rail and can be assembled in minutes (FIGURE 1).4 The variety of rings and blades allows for excellent exposure. Although several complications have been associated with use of the Bookwalter retractor (primarily colon perforation and neuropathy5), they are infrequent and can be minimized by selecting the appropriate blade size and periodically repositioning the blades.

When this or other table-fixed retractors are unavailable, two Balfour retractors, placed at opposite poles of the field to obtain satisfactory exposure, may suffice. With a morbidly obese patient, multiple assistants may still be required to facilitate optimal exposure.

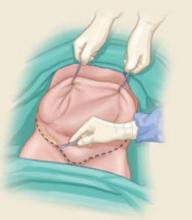

FIGURE 1 A tool to increase exposure

This self-retaining Bookwalter retractor is fixed to the surgical table and features a variety of rings and blades to facilitate exposure.

Thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in hospitalized patients, causing approximately 60,000 deaths every year.6 Obesity increases the risk of deep venous thrombosis in patients undergoing pelvic surgery. Because of their weight—and, often, coexisting conditions such as cardiorespiratory disease—many obese women are inactive or minimally active postoperatively, increasing the risk of thromboembolism, which remains heightened as long as 3 weeks after discharge. Older women are also at high risk, as are those with a malignancy.

Current guidelines call for the application of a pneumatic calf-compression device in the operating room, with removal after the patient is fully ambulatory. I (Dr. Perkins) also advocate simultaneous use of low-dose heparin, which should be given before surgery and continued until discharge.

Although the use of unfractionated heparin in conjunction with spinal or epidural anesthesia is not a major concern, the use of low-molecular-weight heparin warrants consultation with the anesthesiologist. Unfractionated heparin is preferred because it is metabolized much more rapidly than low-molecular weight heparin.7 The main concern with use of heparin in this setting (regardless of the patient’s weight) is spinal hematoma formation.

Inadvertent injury

Because exposure tends to be limited in obese patients, there is an ever-present risk of injury to bowel, bladder, ureter, and vascular structures. In obese women with a history of abdominal surgery, adhesions are likely, and the risk of bowel injury is increased. Similarly, in obese patients undergoing a laparoscopic procedure, many surface landmarks and vessels may be hard to discern.

Consider preoperative bowel preparation when there is a high risk of intestinal injury.8

Use a scalpel to incise the skin and delineate the area to be excised. That area typically consists of a large wedge of abdominal skin and subcutaneous fat.

Although the addition of panniculectomy to gynecologic surgery in the morbidly obese patient is a fairly recent strategy to increase exposure, the procedure itself has roots in the 19th century. In 1910, Howard Kelly of The Johns Hopkins Hospital reported a lipectomy that involved excision of a large wedge of abdominal skin and fat,21 although indications for that lipectomy appear to have been grounded in cosmesis and personal comfort for the patient.

Technique

Panniculectomy involves excision of a large portion of abdominal skin and subcutaneous fat down to, but not including, the rectus fascia, to gain much greater exposure to the lower abdominal cavity and pelvis.

Once the segment to be excised is delineated, it is mobilized using electrocautery to achieve meticulous hemostasis. After all surgical procedures are completed, the abdominal wall is closed in multiple layers, and drains are placed in the subcutaneous layer. Surgeons who have performed this procedure report significantly increased exposure and access to pelvic structures.

Once the skin is incised, the wedge is mobilized using electrocautery, down to, but not including, the rectus fascia.

Risks

The most important risk is impaired healing of the abdominal wound. One study of this procedure in patients on a gynecologic oncology service noted wound complications in 35% of patients, as well as significant blood loss (up to 1,800 mL in one case).22 Another study by Hopkins and associates,23 however, reported minimal blood loss and wound complications.

Caveats

The procedure requires an experienced surgeon, particularly if no plastic surgeon is readily available. Also, when counseling the patient about this procedure, it is important to emphasize that its primary indication is to maximize exposure; cosmetic benefits are secondary.