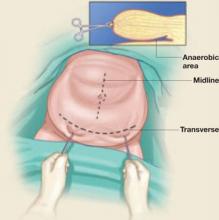

Do not place the incision below the panniculus, in the crease just above the suprapubic mound, though it may be tempting to do so when the panniculus is large and thick. This area is a warm, moist, anaerobic environment that promotes the proliferation of numerous micro-organisms, creating a bacterial cesspool. It is the worst place to make an incision.

If a transverse incision is selected, place caudal traction on the panniculus (which may be facilitated by applying two towel clips to the tissue fold), and incise through the fold at a point approximately three to four fingerbreadths above the symphysis (FIGURE 2).

If a midline incision is selected, a similar technique is appropriate, with downward traction applied to the panniculus and the incision begun at the lower pole of this fold up to the umbilicus—or through it and above, should more room be required.14

After incising the superficial fascia, greater exposure may be gained by incising the rectus sheath beneath the pannicular fold and extending it down to the symphysis. After entering the abdominal cavity, the surgeon may encounter a redundant, fat-laden layer of peritoneum. The edges of this tissue may be temporarily sutured to the edges of the skin incision to remove it from the operative field and obtain better visualization.

FIGURE 2 Incision placement can be counterintuitive

Avoid placing the skin incision beneath the panniculus, an anaerobic area ripe for infection. Instead, retract the panniculus caudally and incise the skin above the fold, as shown.

A few remedies can help when exposure is limited

Exposure is one of the most important elements of successful surgery, but it is often restricted when marked obesity is present. Fortunately, numerous adjuncts are available to address this problem, such as the table-fixed retractor systems described earlier in this article, or one or more of the following tactics:

- Do not try to expose the entire pelvic basin. One technique to ease exploration—especially when more than one procedure is planned—is to refrain from exposing the entire pelvic basin at one time. Instead, focus on obtaining adequate visualization in the immediate area and, once work in that area is finished, concentrate on the next.

- Use extra-long instruments in an extremely large patient, especially if she has a “deep” pelvis.

- Abbreviate the procedure, if possible. Because these cases are technically more difficult and frequently involve excessive blood loss, it may be wiser to perform an “incomplete” procedure, such as supracervical hysterectomy instead of total hysterectomy, depending on the indication.14

- Use a cell-saver blood-collection system if significant blood loss is anticipated. Also remember to give a second dose of prophylactic antibiotic.

Strategies for effective wound closure

The best method of abdominal wound closure has been a subject of debate among both gynecologic and general surgeons. In the obese patient, the key variables are the rather thick subcutaneous fat layer within the abdominal wall and the impact of intra-abdominal pressure on the incision.

What the data show. A number of studies, including one by Montz and colleagues,15 have demonstrated that the running mass-closure technique using delayed-absorbable or permanent suture is just as effective as interrupted suture placement (eg, Smead-Jones closure) but is faster, with less suture deposited in the wound.

The following considerations may also be helpful:

- Approximate the subcutaneous fascia? There has been some debate about whether the subcutaneous fascia must be approximated. My (Dr. Perkins) personal preference in morbidly obese patients is to place several interrupted sutures to obliterate much of the dead space, facilitate skin closure, and minimize tension on the wound; I have noted no significant increase in wound complications using this technique. Placement of a closed-suction drain (eg, Jackson Pratt, Hemovac) is a good alternative.

- Is a drain useful? Some have questioned whether use of a drain increases the likelihood of wound complications,16 but this concern is irrelevant because, in most—if not all—cases, the drainage tubing is exteriorized via a separate stab wound remote from the incision.

- Consider retention sutures. A morbidly obese patient may benefit from through-and-through retention sutures using 0 or #1 permanent material along with rubber bolsters to minimize cutting of the suture into the skin, especially if increased intra-abdominal pressure is likely (FIGURE 3).17 These sutures can be removed on the 10th to 12th postoperative day.

FIGURE 3 Minimize tension on the wound

A morbidly obese patient may benefit from through-and-through retention sutures along with rubber bolsters to minimize cutting of the suture into the skin.

Vaginal surgery does not increase complication rate in the obese

The vaginal approach can be extremely challenging in the morbidly obese patient, especially when hysterectomy is performed. Exposure is often compromised by the large folds about the thighs and buttocks, limiting access to the perineum and vaginal vault. If the patient also has a narrow, contracted pelvis, the difficulty is compounded. Because of these and other concerns about morbidity, many gynecologists hesitate to perform hysterectomy via the vaginal route when the patient is obese.