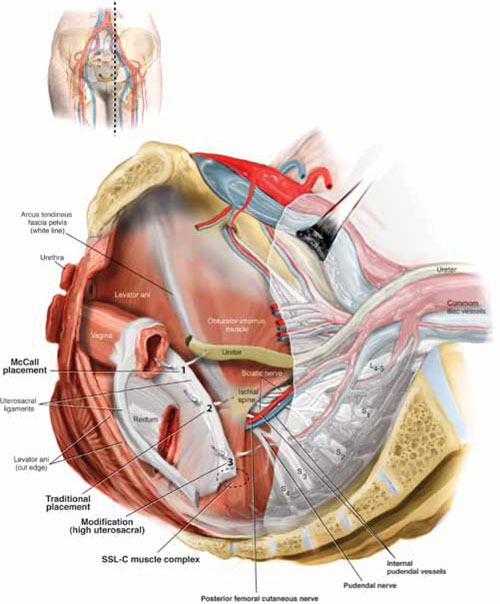

- Pelvic anatomy of high intraperitoneal vaginal vault suspension

- Anatomy of the uterosacral ligament

- High uterosacral suspension (complete uterine procidentia)

- High uterosacral suspension (post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse)

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and Christine Vaccaro, DO, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

The concept of utilizing the uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff and correct an enterocele is nothing new: As early as 1957, Milton McCall described what became known as the McCall culdoplasty, in which sutures incorporated the uterosacral ligaments into the posterior vaginal vault to obliterate the cul-de-sac and suspend or support the vaginal apex at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.1

Later, in the 1990s, Richardson promoted the concept that, in patients who have pelvic organ prolapse, the uterosacral ligaments do not become attenuated, instead, they break at specific points.

Shull and colleagues took this idea and described how utilizing uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff can be performed vaginally—by passing sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligaments near the level of the ischial spine.2

Since Shull described this procedure, numerous published studies have demonstrated outcomes similar to other vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension.3-5

Potential advantages of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are that:

- it provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, making it applicable to all types of vaginal prolapse

- intraperitoneal passage of sutures can be a lot cleaner and simpler than passing sutures, or anchors, through retroperitoneal structures, such as the sacrospinous ligament (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Locating intraperitoneal sutures during uterosacral suspension

Cross-section of the pelvic floor shows where sutures are placed as part of McCall culdoplasty (1), traditional uterosacral suspension (2), and modified high uterosacral suspension (3). Note: High uterosacral suspension may involve passing the suture through the sacrospinous ligament–coccygeus (SSL-C) muscle complex (dashed oval) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may, at times, lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures in this procedure are passed too far laterally.2-5

High uterosacral suspension has been our operation of choice for 11 years for patients who have pelvic organ prolapse in which the peritoneum is accessible (see “How this procedure evolved in our hands”). In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of the procedure. Four accompanying videos that further illuminate those steps are noted in the text here at appropriate places.(For example, Video #1, immediately below, sets the stage for the step-by-step discussion by reviewing pertinent pelvic anatomy.)

- When we first performed high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues,1 we mobilized vaginal muscularis off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and Posterior vaginal walls.

- Initially, we thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that were separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele.

- We have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex. At times, a small window can be made in the peritoneum that provides direct access to this complex (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 3).

References

1. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

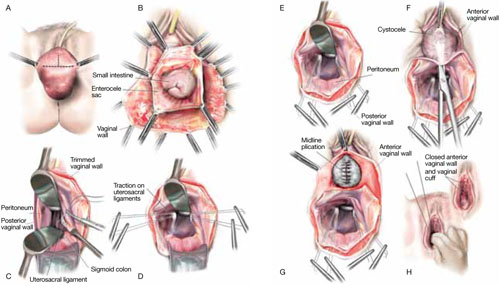

1. Enter the peritoneum

It’s our opinion that, even though extraperitoneal uterosacral suspension procedures have been described, the pertinent anatomic structures (again, see Video #1) are not easily identifiable unless suspension is undertaken intraperitoneally. Entering the peritoneum is, obviously, not a concern if the patient is undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. If the patient has post-hysterectomy prolapse, however, you must be able to isolate an enterocele and enter the peritoneum (follow FIGURE 2, beginning here and through subsequent steps of the procedure).

FIGURE 2 Step by step: High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension