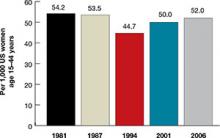

Women spend about 5 years of their reproductive lives trying to get pregnant and the other three decades trying to avoid it.1 Nearly half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of these end in abortion.2 In the past 15 years, new contraceptive options have been developed to address this staggering statistic (FIGURE 1). Despite these innovations, the unintended pregnancy rate has increased continually since 1994 (FIGURE 2).23

What are we doing wrong? In this article, we will review how recent innovations are disseminated through the medical community in the context of three specific contraceptive technologies:

-

hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure)

-

ulipristal acetate emergency contraception (Ella)

-

the 13.5-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Skyla).

In the process, we assess the available data on the intended and potential impacts of these technologies and describe how ObGyns can best translate these data when considering how to incorporate these new technologies into practice.

| FIGURE 2: Changes in the unintended pregnancy rate, 1981–2006 |

How contraceptive technologies spread in the medical community

Innovations spread through communication channels between individuals of a social network, who are then given time to adopt them. As opinion leaders of a social network become early adopters of a technology, dissemination of the innovation through the social network accelerates.4 This phenomenon is best described by the “diffusion of innovations theory” popularized in 1962 by sociologist Everett Rogers for agricultural applications; he also applied the model to public health.5 The variables he determined to be involved in the acceptance of an innovation are:

-

its relative advantage compared with existing technologies

-

compatibility with current practice

-

low complexity

-

high “trialability” (a potential adopter can easily attempt to use the innovation in his or her practice)

-

high “observability” (the results are easily observed and described to colleagues).

In contrast to new technology itself, medical evidence does not spread rapidly. Data generally spread far more slowly than new technology, typically taking longer than 10 years to influence medical practice.6,7 Opinion leaders can impair the dissemination of data by relying on anecdotal evidence to justify their recommendations.8 Negative findings that challenge these intuitive beliefs can take even longer to disseminate, allowing certain innovations to diffuse through the medical community faster than reports of any associated problems.9

Related article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

How hysteroscopic sterilization gained widespread adoption

Gariepy AM, Creinin MD, Schwarz EB, Smith KJ. Reliability of laparoscopic compared with hysteroscopic sterilization at 1 year: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2):273–279.

Since its introduction into the market in 2002, more than 650,000 Essure hysteroscopic sterilization procedures have been performed worldwide.10 This procedure has diffused quickly through the medical community because of the characteristics we mentioned earlier, which ease acceptance in any network:

-

Relative advantage compared with existing technologies. Compared with existing laparoscopic sterilization methods, hysteroscopic sterilization was seen as a less invasive office procedure that could be performed more cost-effectively under local anesthesia, with very high efficacy, if successful.

-

Compatibility with current practice. Because many clinicians were providing in-office hysteroscopy, adding sterilization was a simple step.

-

Low complexity. Hysteroscopic sterilization builds on operative hysteroscopic skills with which gynecologists are familiar.

-

High trialability. The manufacturer’s representatives were willing to bring the instruments to any office for clinicians to try in their practice. The company worked with hysteroscopic equipment companies to create significant discounts for providers who would perform the procedure regularly.

-

High observability. Successful deployment of the devices, and the appearance of the confirmation test, were visualized and described easily as clinicians spoke to other clinicians, helping with dissemination.

Despite these features, however, new data suggest that hysteroscopic sterilization is less effective than laparoscopic sterilization. A successful Essure procedure requires:

-

visualization of both tubal ostia on hysteroscopy

-

successful deployment of the microinserts at the appropriate position

-

hysterosalpingography at least 3 months later (with use of an alternate form of contraception in the interim)

-

demonstrated tubal occlusion by the Essure devices (not by tubal spasm) on hysterosalpingogram.